Protecting Indonesian rivers with wayang

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

An activist in Jepara fights to protect rivers from pollution with puppets.

“Rivers are the beginning of civilizations,” Muhammad Hasan, puppet master and storyteller from Kecapi village, Jepara regency, Central Java, said. “Rivers give life.”

In his village, life indeed centers around rivers. Situated at the foot of Mount Muria, Kecapi is surrounded with rivers flowing down from freshwater springs on the dormant volcano. One of them is Kali Gayam (Gayam River), which is the hub of the village’s activities, including bathing and washing.

In his childhood, Hasan had to walk five kilometers down this river to reach his elementary school in another village.

“Sometimes, my friends and I went fishing [at the river] on the way home,” Hasan recalled during an interview with The Jakarta Post in Baca Di Tebet, South Jakarta, on Feb. 26. “By using a few grains of rice as baits, we managed to catch a lot of big fish.”

“There aren’t many [big fish] in the river now,” he added, with a sad smile.

Over the years, many rivers in Jepara have become polluted, thus reducing the wildlife population in them.

“Garment home industries have been growing rapidly in Jepara within the past 10 years,” Hasan said. “Many of them dispose their wastewater directly into the rivers.”

One of the most well-known centers of garment home industries in Jepara is Troso, Kecapi’s next-door neighbor. Thousands of families in this village are engaged in producing Tenun Troso (Troso’s Handwoven Textile), which has been exported to many countries around the world.

Their wastewater, coming in various vibrant colors from the chemical dyes, pollutes the village’s rivers, wells and even paddy fields.

Hasan and his friends, who are concerned with environmental protection, have been protesting directly to the villagers and village’s officials to no avail.

“We couldn’t do much as [the garment home industry] concerns the livelihood of many people,” he said.

While there is no garment industry in Kecapi village, its rivers are polluted with sachets of shampoo and detergent disposed by its own villagers.

“[The villagers] believed [littering into the rivers] was okay because rain always washed all the garbage downstream, leaving our rivers clean again,” Hasan said, with a chuckle.

Hasan, together with his friends and volunteers at Rumah Belajar Ilalang (Ilalang House of Learning), a children’s and teens’ community he founded in 2011, then created Wayang Kali (River Puppets) in order to inspire people to protect the environment.

“We’re trying to save the rivers via this artistic approach,” the 35-year-old (Hasan) said.

Wayang Kali

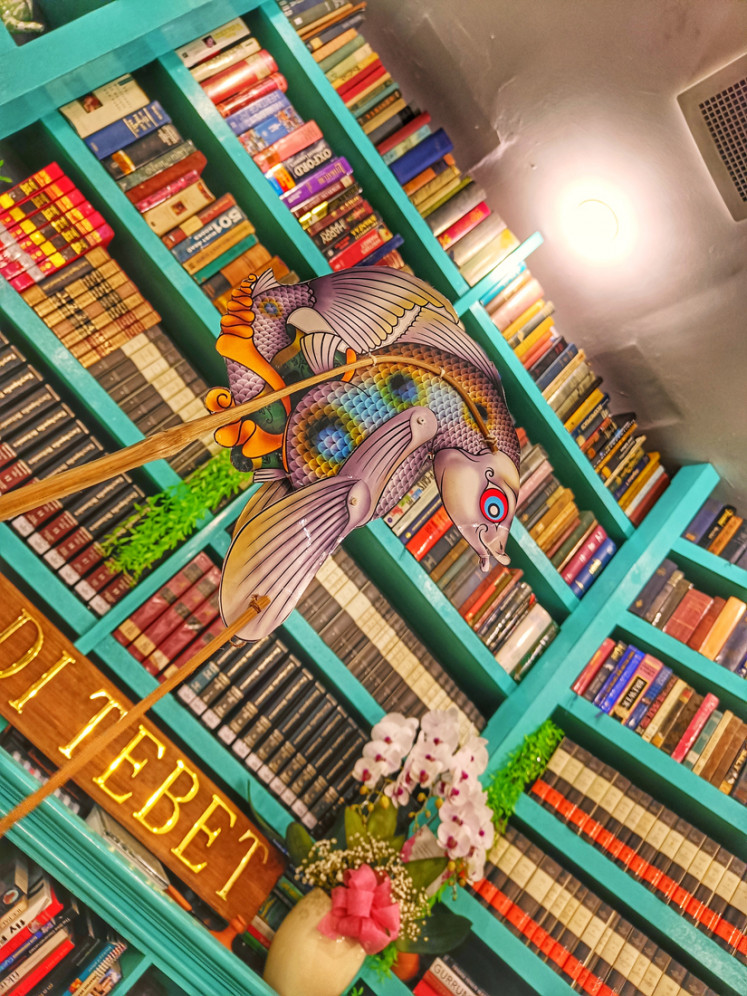

Wayang Kali, made of recycled compact discs and PVC, features characters of eels, fish, frogs, turtles and many other animals we usually encounter in rivers.

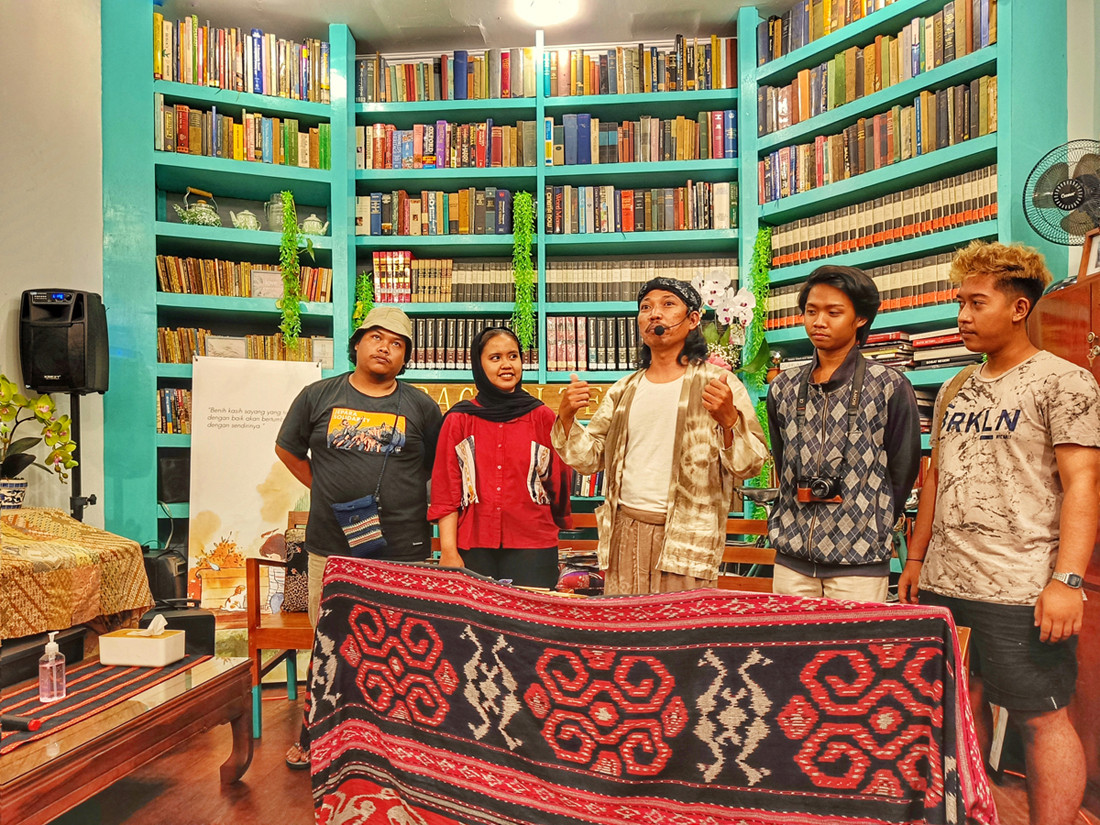

On the evening of Feb. 26, the man, who is dubbed Den Hasan, narrated a story titled “Mulia di Tanah Muria” (Glory on the Land of Muria) in front of dozens of audience members in Baca Di Tebet.

The 30-minute story highlights an episode in which Ikan Kutuk (Snakehead Murrel) gets sick after eating small insects that fly by the river, as these insects have been poisoned with an insecticide sprayed by humans.

Hasan narrated the story with zest and humor, prompting the audience to also participate in the performance.

“Unlike traditional wayangs that feature kings and warriors as their characters, Wayang Kali features fish and animals that we’re all familiar with,” Wien Muldian, literary agent and cofounder of Baca Di Tebet, said. “Therefore, it’s easier for many of us to relate to the story.”

Hasan, who is currently studying communication at Nahdatul Ulama Islamic University (UNISNU) Jepara, always highlights environmental issues during his Wayang Kali performances.

In Jepara, the puppet master usually performs in communities, markets, schools and pengajian (Islamic study groups).

“When performing in pengajian, I always highlight the hadiths regarding environmental protection,” Hasan said. “These hadiths are rarely recited these days. But I think it’s necessary to remind people humans are actually God’s stewards, assigned to protect every living creature on earth.”

Indonesian author Kanti W. Janis, who watched the Wayang Kali performance in Baca Di Tebet that evening, lauded Hasan’s efforts.

“There’s a strong message against pollution behind Den Hasan’s artistic performance,” Kanti said. “I hope his fight against pollution will continue.”

Den Hasan was awarded a certificate by the Indonesian World Records Museum (MURI) in 2017 for performing in 468 locations in 195 villages around Jepara for 21 days on the occasion of Jepara’s 486th anniversary.

Children advocacy

Hasan’s hard work has somewhat paid off. After getting hooked on Wayang Kali, children in Kecapi village urged their parents to stop littering into the rivers.

“Teenagers in our village also made trash cans and stationed them near the spots where people usually bathe and wash clothes [in the rivers] so they can easily dispose of used sachets in [the trash cans],” he said.

And the villagers also agreed to take turns in emptying and cleaning the trash cans when they become full.

“It’s all done by children’s advocacy,” the father of two (Hasan) said, with a big smile. “I feel so proud of them.”

But unfortunately, things have not changed much in Jepara’s garment center in Troso village. People still dispose of the textile’s wastewater, laden with heavy chemicals, directly into the rivers.

“We won’t give up,” Hasan said. “My friends and I will keep on speaking up on this issue until the people realize they need to change.”

Some of the volunteers at Rumah Belajar Ilalang make clothes with natural dyes to encourage people to shift from chemical colorings. One of them is Nikmatul Hanik, who creates Shibori-style textiles by using natural dyes made from local plants.

“These natural dyes are eco-friendly,” Hanik said. “Their wastewater won’t harm the environment even when it’s thrown directly into the rivers.”

That evening, Hasan was wearing Hanik’s brown Shibori outer, dyed with Indian almond (Terminalia catappa) and alum, during the wayang performance in Baca Di Tebet.

In the long term, Hasan plans to compile the stories he has written for Wayang Kali into a book in order to reach more people.

“It’s been my dream to compile [the Wayang Kali stories] into a babon [Javanese: anthology], just like the Mahabharata and Ramayana stories,” Hasan concluded.