Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsBook Review: How Indonesia became an archipelagic state in 'Sovereignty and the Sea'

The book examines the history of how the concept of the archipelagic state came into being.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

T

he creation of the concept of the archipelagic state is one of the most innovative developments in the history of the law of the sea. It enables states made up of numerous islands and other land features to bring the ocean and the seas that connect their land territory under national jurisdiction, for the exploitation of natural resources, communication and security.

The newly released Sovereignty and the Sea: How Indonesia Became an Archipelagic state is the work of distinguished professors John G. Butcher and R.E. Elson. The book examines the history of how the concept of the archipelagic state came into being and how it became recognized internationally through over two decades’ diplomatic campaign, resulting in a balanced regime adopted under the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).

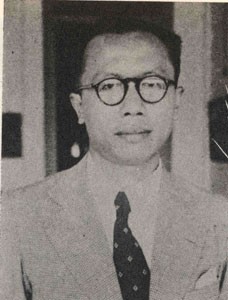

The first two chapters set the historical background of the formation of Indonesia as a sovereign state and the challenges faced to unite anation. There were many officials and legal advisors consulted by the then president to resolve those challenges, but it was Mochtar Kusumaatmadja, a young civil servant in his late 20s and later foreign minister, who designed a vision of a territory unity of Indonesia that later became the impetus of the archipelagic state.

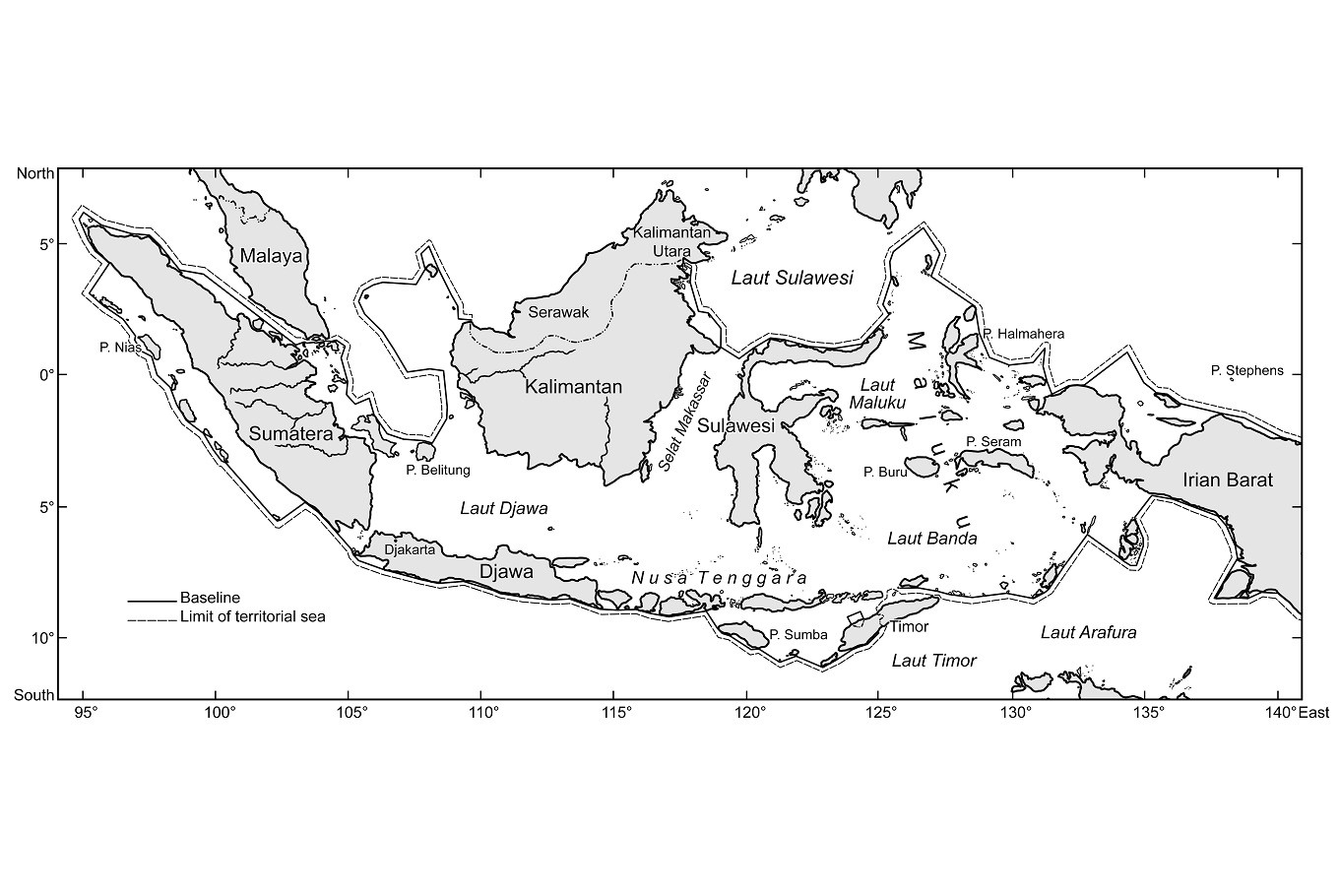

Indonesia issued a statement titled “Government Announcement Concerning the Water Territory of the Republic of Indonesia”(Chapter 3) on Dec. 13, 1957 to declare its sovereignty over all waters surrounding, between and connecting all of its islands. The declaration was heavily criticized by the western maritime countries, and the Indonesian delegation merely had the opportunity to propound the rationale behind their declaration at the First United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea in 1958.

Indonesian waters according to the map accompanying Law No. 4 of 1960. This map has been redrawn from the map accompanying Law No. 4 (Full image credit is available on p. 502 of the 'Sovereignty and the Sea' book).(NUS Press/File)

Indonesian waters according to the map accompanying Law No. 4 of 1960. This map has been redrawn from the map accompanying Law No. 4 (Full image credit is available on p. 502 of the 'Sovereignty and the Sea' book).(NUS Press/File)

Indonesia, nonetheless, pressed ahead with Government Regulation in Lieu of a Law No.4 of 1960 (Chapter 5) and mounted a diplomatic campaign to gain support. The campaign, directly related to maritime issues, proved to be a lengthy, intense and difficult process, which was only successful for its historical context, determined politicians and a number of dedicated diplomats equipped with knowledge of international law.

Since 1969, Indonesia negotiated its maritime boundaries with neighboring states, including Australia, India, Malaysia, Singapore, and Thailand. On various occasions, Indonesia compromised with neighbours, giving them a bigger portion of disputed areas in exchange to use base points defined under Law No.4 1960, in an effort to gain implicit recognition of the archipelagic concept. But the real battle to gain international recognition was at the Third UN Conference on the Law of the Sea.

To promote the archipelagic concept before the negotiation, Mochtar in a major academic conference appealed to officials and lawyers in the audience to “think not like a craftsman – ‘the cobbler, a plumber or a carpenter’ – who worked within the confines of existing international law but as a ‘master builder or architect with a mission to build a new and better world’” (Chapter 8).

To craft and build a new regime on archipelagic state became the Indonesian delegation’s most important goal.

Djuanda Kartawidjaja, the 11th and final Prime Minister of Indonesia.(Wikimedia Commons/File)

Djuanda Kartawidjaja, the 11th and final Prime Minister of Indonesia.(Wikimedia Commons/File)

The battle was centered on a number of fundamental issues. First, the definition of the archipelago; second, the objective criteria to define an archipelagic state; third, the passage regime; fourth, the preservation of rights and interests for neighboring states; fifth, inevitably, as the regime of archipelagic state was negotiated within the bigger package at the third conference, to find a solution for the regime governing straits used for international navigation.

As the general understanding was that specific issues should be negotiated through “informal consultations among those most interested”, the text on archipelagic was essentially prepared based on the negotiation between Indonesia and the United States. It was only at the sixth session in 1977, through numerous rounds of talks and negotiations that the two states reached a grand compromise on the package of the archipelagic nation (Chapter 16).

The section on archipelagic state has since become an integrated part of a balanced package between competing interests that had been laboriously crafted and later enriched into UNCLOS with minor amendments.

The concept of the archipelagic state – first as a successful maritime power opposition, eventually as a limited conditional recognition and eventually universal acceptance of a compromise solution – gavethe archipelagic state sovereignty over the archipelagic waters, while preserving freedom of communication including navigation and overflight for all states.

The Indonesian delegation to the United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea, Geneva, 1958. Ahmad Subardjo Djoyoadisuryo is third from left, Mochtar Kusumaatmadja third from right.(Indonesian Spectator, 1 April 1958/File)

The Indonesian delegation to the United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea, Geneva, 1958. Ahmad Subardjo Djoyoadisuryo is third from left, Mochtar Kusumaatmadja third from right.(Indonesian Spectator, 1 April 1958/File)

It was not all Indonesia had hoped and fought for, but it was the best result they could have achieved under the circumstances. It was a compromise to accept something that falls short of the perfect in order to achieve the desirable.

The book has achieved what the two authors set off to do. Among others, it brought out clearly the multidimensional nature of Indonesia’s archipelagic campaign, demonstrated the connections between its different strands, and showed more clearly how the campaign outcome was closely tied to broader developments of the law of the sea, particularly at the third UN conference.

Although the two authors were denied access to the Indonesian national archives, they managed to provide details on the most important negotiations between Indonesian officials and their counterparts in other states, particularly the US, through consulting previous works and conducting interviews with scholars and diplomats.

What was also highlighted in the book was the significant contribution made by the dedicated Indonesian delegation led by Mochtar, Hasjim Djalal and other officials. During the campaign, the officials were determined to gain international recognition of Indonesia’s unity that they believed was already in existence, and now it is on the shoulders of the next generation to carry on the work to implement the archipelagic regime and to ensure Indonesia stands as an important maritime state.

---------------

We are looking for information, opinions, and in-depth analysis from experts or scholars in a variety of fields. We choose articles based on facts or opinions about general news, as well as quality analysis and commentary about Indonesia or international events. Send your piece to academia@jakpost.com. For more information click here.