Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsWanted: Women's voices from the movement

Here in Indonesia, the women’s movement has a long history, dating back to the turn of the century. In 1928, the first Indonesian Women’s Congress was organized. There were many active women’s political organizations of different ideologies.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

A

s of 2019, there are 131 women members of the United States congress, the largest number ever. More significant perhaps is the fact that it is from among these women that the sharpest and most critical voices on issues of social justice and democracy have emerged. Two currently popular names are Alexandria Ocasio Cortez (AOC) and Ilhan Omar. Their voices and actions have sparked a new hope among those wishing for social progress and change.

These two women also represent a sector of society that has long been under-represented in the mainstream institutions of the American political system. At 29, AOC is the youngest ever member of the US Congress. She is of Hispanic background; while she has served on various Democratic Party campaigns, her last paid job has been as a waiter and barista. She is not only a member of the Democratic Party but also of the more activist Democratic Socialists.

Meanwhile Omar came to the US as a child. Her family was refugees from Somalia. She became a US citizen at age 17, studied political science at university and threw herself into politics. Her activism was not through the electoral party. She was also, for example, Director of Policy Initiatives of the Women Organizing Women Network. She was the first Muslim woman of African descent to be elected to the US congress and with a vote of 78 percent in her electorate in Minnesota, defying Islamophobic attacks against her. She is the first woman in the US congress to wear a hijab but has not been known as a politician using or profiling religion.

These two women are not products of the Democratic Party machine. In fact, they have both had to fight and defeat the party’s established leaderships in order to be elected. Still, even after election, they are in constant conflict with that establishment. If they are not products of the party machine, where have they come from? Over the last several years, a series of quite militant social movements have been emerging. These include the Black Lives Matter movement protesting the killings of black people by police. There has also been the Me Too movement protesting sexual harassment of women by men in positions of power. Since the presidential election of Donald Trump there have been big women’s marches against misogyny. There are movements in solidarity with migrants and refugees. It is out of an atmosphere created by this mounting activism that we see figures emerge such as AOC and Omar.

The election of 131 women is also a product of this atmosphere, even if not all these women are progressive, and some even reactionary. The election of Omar, who has spoken out with great courage against the US intervention in Venezuela and against US support for Israel’s repressive policies against Palestine, as well as support for refugee rights, free education and increase in wages in the US, marks her out as not simply as “representative of women” but of new more radical voices. AOC’s campaign for a “green New Deal” to fight global warming, and also for a free education and better wages puts her in the same category.

Here in Indonesia, the women’s movement has a long history, dating back to the turn of the century. In 1928, the first Indonesian Women’s Congress was organized. There were many active women’s political organizations of different ideologies. The biggest was easily the Gerakan Wanita Indonesia (Gerwani) that was active up until 1965, when it was suppressed with the rest of the Left. Between the 1970s and 2000s, activity in support of women’s rights continued, both under and after the New Order regime. In more recent times, there have been gains in legislation requiring affirmative action in favor of women. Most recently, General Elections Law No. 7/2017 requires 30 percent of a party’s candidates to be women, and that there must be at least one woman in every three candidates listed. This has resulted in some increase in the number of women in legislative bodies, and there are also now well-known women cabinet ministers. Vocal lawmakers have included Rieke Diah Pitaloka, Rahayu Saraswati Djojohadikusumo and Eva Sundari.

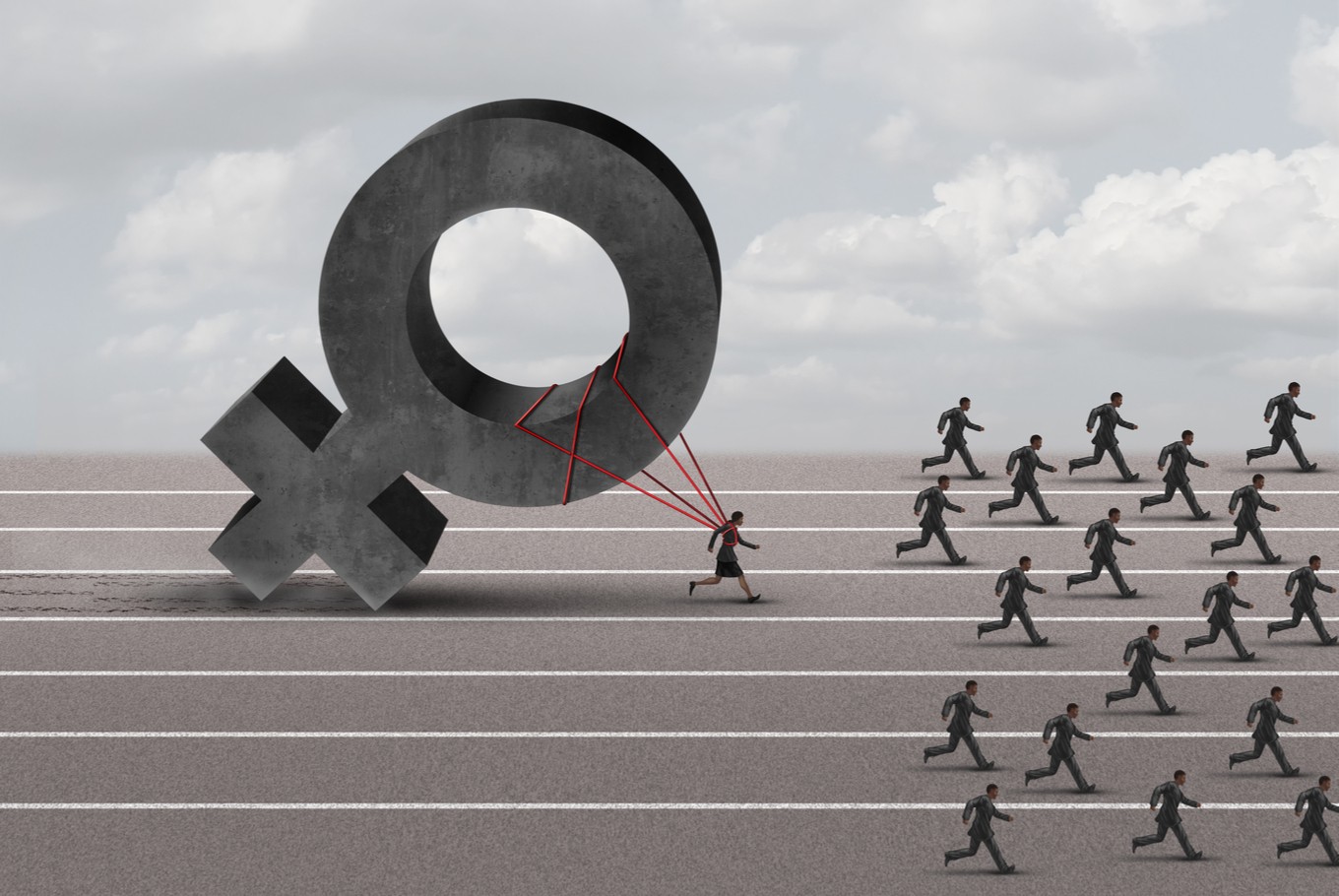

However, over time their energies have been drained by the low cultural level of elite politics, with its endemic corruption, policy free competition for spoils and a heavy machine bureaucracy. The AOC and Ilhan Omar phenomenon has not arrived in Indonesia yet. There are even still massive problems in getting the bill for the elimination of sexual violence passed.

The affirmative action policy is there to ensure women’s participation. Quotas, however, cannot guarantee commitment to progressive policies. In these last weeks of the election campaign, street posters calling for support for women election candidates can be seen everywhere as are various social media postings. However, the rhetoric of these candidates can hardly be distinguished from that of the men and, more importantly, there are no signs of critical voices challenging the Establishment on issues such as wages policy, LGBT rights, environmental issues, human rights violations immunity or even campaigning for the passing of the above bill. The Establishment bears down on them so hard even to the extent of them ending up changing their dress: women who never usually wore the hijab are suddenly wearing them.

One lesson we can perhaps learn from the US experience, which is probably not unique, is that the answer is not some kind of technocratic reform of the political parties. The answer is for more of us, and especially the youth, to be building active social and political movements in the streets and workplaces. A start has, of course, already been made. The brave and consistent militancy of the Kamisan (Thursday) rallies over many years in many towns demanding actions on various human rights violations including the disappeared activists from 1998 is one great example. There have been also women’s marches in many towns. Labor unions, including those whose members are mostly women, have been more active. Solidarity with LGBT rights has been more visible.

These movements, however, have not reached the necessary scale required to truly change the political atmosphere, to impact on our deadened political culture. Whether the aim is simply to increase women’s involvement in real politics to reflect the fact that Indonesia’s 266 million people are divided almost 50-50 between men and women -- let alone to strengthen a culture of anti-sexism and social justice generally, the solution will not be found with tinkering further with election laws or regulation or NGOs trying to re-educate party politicians.

The energy of Kamisan, of the Women’s Marches, needs to explode onto the national stage. Laws defending freedom of expression and organization protect our rights, but only our collective energy will make them real.

***

The writer is an activist, playwright, theatre producer and director.