Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsThe rise, crumbling of reformist populism in Indonesia (Part 2 of 2)

In short, the populist openings were not bad but a positive way to enable more democratization while also fostering human rights and liberal economic development. However, there were serious setbacks.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

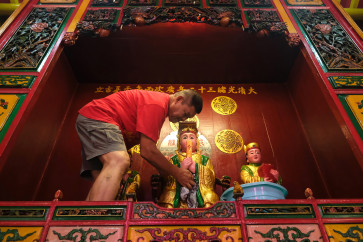

Once reelected, Jokowi accommodated his major political opponents (even Prabowo) as well as the lawmakers (including from the PDI-P) that now weaken the anti-corruption agency and the regulations on mining and land acquisition, plus revised the Criminal Code to reduce critical freedoms. This is power-sharing, not democracy. (JP/Syelanita)

Once reelected, Jokowi accommodated his major political opponents (even Prabowo) as well as the lawmakers (including from the PDI-P) that now weaken the anti-corruption agency and the regulations on mining and land acquisition, plus revised the Criminal Code to reduce critical freedoms. This is power-sharing, not democracy. (JP/Syelanita)

I

n short, the populist openings were not bad but a positive way to enable more democratization while also fostering human rights and liberal economic development. The Economist, for one, applauded.

However, there were serious setbacks. The social pact in Surakarta declined when then-mayor Joko “Jokowi” Widodo left for Jakarta. The broad alliance for public welfare was also not sustained. In the 2014 presidential elections, the best organized trade union confederation even supported infamous former general and business oligarch Prabowo Subianto in return for favors.

Moreover, when Jokowi had won with a thin margin and formed his government, he did not mainly rely on the prodemocracy movement but the economic and political elite, including in “his” Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (PDI-P); and he failed to use the anti-corruption agency to contain dirty politics. In the face of the 2016 gubernatorial elections in Jakarta, then-governor Basuki “Ahok” Tjahaja Purnama, ethnic Chinese and Christian, prioritized Singaporean-style management, dishonored the promises to the urban poor, and made ill-advised statements about his opponents’ abuse of a verse in the Quran, resulting in people abandoning him.

Hence, the field was wide open for Ahok’s (and Jokowi’s) contenders to foster conservative populism, accusing Ahok for being against Islam in general and poor Muslims in particular. Huge masses were mobilized in the streets. Established critics of Jokowi’s regime nourished extreme Muslim groups. Ahok was sentenced for blasphemy and lost the election.

When the 2019 presidential elections were coming near, similar critique and increasingly strong Muslim groups began to be mobilized against Jokowi. To counter this, Jokowi once again did not mobilize the popular movements but relied on illiberal measures, political accommodation of conservative Muslim ideas and groups (even appointing a major conservative Muslim ulema as his vice president candidate), related political triangulation and the revival of Indonesia’s socioreligious and ethnic politics.

Once reelected, Jokowi accommodated his major political opponents (even Prabowo) as well as the lawmakers (including from the PDI-P) that now weaken the anti-corruption agency and the regulations on mining and land acquisition, plus revised the Criminal Code to reduce critical freedoms. This is power-sharing, not democracy.

Even though the students reclaimed the streets to protest, Jokowi stated in his inaugural address that the main thing was not the process but the results in terms of international-oriented economic development. This resembles European practices of defending liberal economic globalization while conceding to chauvinist populist resistance against international engagement for democracy and human rights. Despite Jokowi’s pro-business line, The Economist is now worried.