Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsBeyond fear toward trust: Using dual role of emotion in COVID-19 mitigation, recovery

In the unprecedented global crisis brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic, sensitivity to emotion in policymaking is both necessary and a necessity for the success of the government’s disease control and management efforts toward building civil resilience.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

T

ransparency and empathy are perceived as essential to building the public trust that is necessary to building effective COVID-19 policies. While transparency has been discussed broadly and at length, discussions on empathy have been rather absent in the political arena.

Empathy is just one of the emotional responses to the unprecedented pandemic. Fear of death, distrust of the government, concerns over social chaos, anxiety over job loss and a global economic crisis are some other emotional responses to the possible impacts of COVID-19. World leaders have used phrases like take courage, don’t panic and be kind in their speeches to build public trust and help people look beyond fear.

However, COVID-19 has presented an entirely new and unprecedented challenge to all societies and governments. Lack of knowledge about SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes the disease, has caused confusion around the world.

No country is immune to the virus, and this has prompted a variety of human responses, including among policymakers. Some policymakers have a grasp on the issues at hand, while others have missed the mark.

This essay examines how understanding the roles emotion plays in human behavior can help understand how decisions are made in the context of state-society relations during the pandemic. Understanding the psychological aspects of decision-making and information delivery with regard to COVID-19 is critical to understanding how people might behave toward certain policies, such as lockdowns and physical distancing.

Emotion, reason and policy

According to the American Psychological Association, emotion is “a complex reaction pattern, involving experiential, behavioral, and physiological elements by which an individual attempts to deal with a personally significant matter or event”.

In general, however, emotion is often viewed as negative, bad, weak and irrational. Many philosophers and scholars also perceive emotion as opposite and subordinate to reason, or rationality. Emotion is to do with consequences, mistakes and misconceptions. This is the characteristic that Jonathan Mercer has identified as epiphenomenal and a source of irrationality.

In fact, psychologists and neuroscientists have found that emotion determines our worldview and helps us make decisions, as it is intertwined with cognition (emotion as rational). Emotion is also part of an efficient strategy for gaining material advantages (emotion as strategy).

Although this approach is rather instrumentalist, emotion is recognized as part of the solution rather than merely the cause of problems. In the decision-making process, emotion helps us to better understand how actors will frame information, develop a sense of identity and constitute a political community, and how a community can heal after trauma. This also implies that emotion is not limited to individuals and that it has a social dimension; for example, when people relate to collective situations such as the transboundary COVID-19 pandemic. In this case, since a nation-state is an imagined political construct run by human beings, state behavior can also be analyzed through the emotional aspects.

Furthermore, emotion is important in looking at how society might judge policy. According to the introduction to an article by Richard D. French published on the LSE blog, “ordinary citizens judge policies based upon the meaning they attach to it, rather than undertaking a rigorous ‘rational’ analysis”.They refer to their own experiences when they react to policy, and this indicates whether they will obey or disobey a policy the government has made.

Indonesia’s series of misconceptions

In the first two months of 2020, Indonesia rejected the very notion that COVID-19 would emerge in the country. Indonesian Health Minister Terawan Putranto assured the public that COVID-19 was unlikely to emerge in Indonesia and that there was no government cover-up, and instead called on the Indonesian people to enjoy life, eat well and remember to pray.

Denial was also indicated in the series of statements made by other ministers, who joked that Indonesians were immune to COVID-19 since they had a ‘restricted license’ for bringing it into the country. The compassionless joking eventually stopped when the country’s first two confirmed cases of COVID-19 were announced on March 2.

After declaring a national emergency on March 14, President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo admitted that the government was withholding some information to prevent public hysteria and avoid stigmatizing people who had contracted the disease. The day before, another decision was made that engendered misperception when the government declared the 188 Indonesian crew members of the World Dreamcruise ship as “Coronavirus Immunity Ambassadors” who would inspire all Indonesian citizens to live healthily to boost their “immunity”.

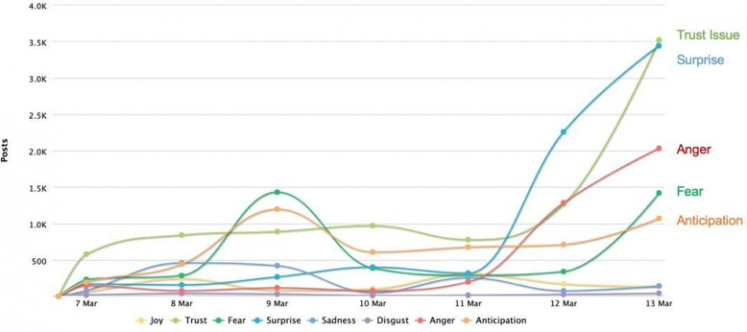

According to the DroneEmprit analysis published in early March on emotion and public perception regarding the government’s approach to COVID-19 mitigation (based on data gathered from March 7 to 14, 2020), trust issues dominated public perception, followed by surprise, anger and fear (Graphic 1). Public trust primarily concerned the accuracy and transparency the government’s data, which illustrates President Jokowi’s misconception about transparent data. People tend to demand transparency when they are afraid; without it, the government loses public trust.

Meanwhile, the public reacted with surprise to a dramatic increase in the death toll. Their anger was directed toward those who politicized COVID-19, such as social media buzzer (an Indonesian term referring those who generate buzz on social media) and politicians. Fear not only relates to public trust in government, but also describes the helplessness citizens feel about their incomprehension of the situation.

Graphic 1: The Indonesian public's emotional response to COVID-19 (Drone Emprit (2020)/via CSIS)These emotional responses show how trust issues have come to dominate state-society relations in Indonesia amid the COVID-19 epidemic in the country. This behavioral relationship between the government and the public is by no means isolated to COVID-19, and it must be acknowledged that state-society relations in Indonesia have been tense during the Jokowi administration.

However, this does not mean that Indonesia is at all helpless. Although the stigmatization of COVID-19 patients, aggressive objections to burying the COVID-19 dead and civil disobedience exists with regard to the government’s COVID-19 policies, civil society in Indonesia has embraced the traditional spirit and culture of gotong royong (mutual cooperation) through volunteerism and crowdfunding campaigns. Therefore, compassion and resilience prevails in society during this difficult time, beyond the ideas of the nation-state and governance.

Beyond Indonesia: Emotion and constructive COVID-19 mitigation

While there is no one-size-fits-all policy to combat COVID-19, applying the lessons learned is surely invaluable under the current circumstances. One of Indonesia’s takeaways is to adopt a more sensitive, compassionate approach to communicating information on the coronavirus.

Sensitivity to emotion can be employed in several ways to help citizens overcome their fears and to rebuild public trust as the essence of successful policymaking.

First, it prompts the development of collective identities in government and society. World leaders have adopted a compassionate approach to public discourse with an aim to reduce anxiety among their citizens who do not understand the kind of enemy they are facing.

Countries like Singapore and South Korea have experienced previous outbreaks of coronaviruses (SARS and MERS), so they were generally better prepared. Although the characteristics of the COVID-19 virus may still be unknown, various policies have proved relatively effective at flattening the curve of infection.

In a webinar on South Korea’s COVID-19 experience produced by the Centre for Strategic and International Studies Indonesia (CSIS Indonesia), Gil H. Park of Daegu University says that sensitivity to emotion played an important role. The government must have a communication strategy based on a compassionate approach, which will allay the public's fear and anger while presenting fact-driven information that is gathered and delivered by experts and the private sector. South Korea has applied social distancing to family units to alleviate individual fears of becoming a “virus spreader”, which implies the government’s compassion and consciousness in avoiding blaming others.

Singapore has taken the opposite approach. Although its government has shown great performance in providing public facilities and enforcing public compliance, some Singaporeans have taken to WhatsApp to scapegoat foreign workers as COVID-19 spreaders.

Success stories are not limited to high-income countries like Singapore and South Korea; take Vietnam, for example. According to an article in The Diplomat by Minh Vu and Bich T. Tran, the secret to Vietnam’s low number of confirmed cases is its proactive approach to prevention through evidence-based policymaking and “the mobilization of nationalism”. Through the latter, Vietnam “framed the virus as a common foreign enemy”.

In adopting a sensitive approach, the government reframed the public’s fear of COVID-19 in the narrative of a unified community and correctly co-opted the Vietnamese sense of nationalism (as a sociopolitical dimension of emotion) into its approach to COVID-19 mitigation. Nationalism, without disregarding the importance of transparency, became its strategy to mobilize a collective humanitarian response against the virus.

Second, emotions reflected in the representations of women. According to The Guardian’s article on female politicians and COVID-19 management, New Zealand's Prime Minister has been praised for her science-based, empathetic approach to risk communication. Ever since the 2019 Christchurch mosque shootings, Jacinda Ardern has become well known for her “feminine style” of politics that is empathetic, decisive and down-to-earth. Another example is Taiwanese President Tsai Ing-wen’s warm, authoritative style. The two leaders’ styles have engendered trust and compliance among their citizens and even political opponents. That female leaders have a special touch in managing the epidemic is, however, a hypothesis that does not apply to Aung San Suu Kyi.

Third, a compassionate approach in the discourse on global solidarity can be used as a strategy to gain material advantages for COVID-19 mitigation and recovery. During the confusion of the early months of the pandemic, states took the “every man for himself” approach. As Stephen Walt writes in Foreign Policy, the pandemic has reified the importance of the state as “the main actors in global politics” and “made effective cooperation among states” difficult to achieve. On gaining more insight into the impacts of COVID-19 on externalities, however, states realize that they need international cooperation.

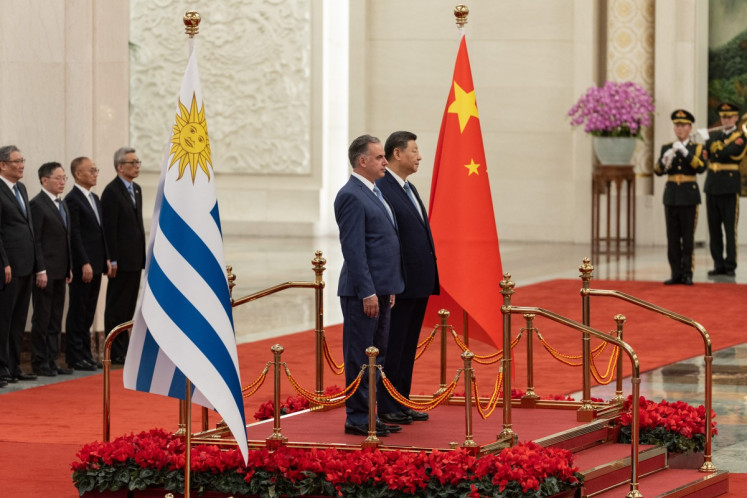

This behavior shows how foreign policymakers were as surprised as ordinary citizens were by the magnitude of the coronavirus. For example, ASEAN has gradually gained ground on the regional pandemic through its spirit of solidarity as seen in the Special ASEAN-China Foreign Ministers' Meeting on Coronavirus Disease, the ASEAN Special Summit and the ASEAN Plus Three Special Summit. However, these platforms are still in the proposal stage for material advantages such as research and development, economic recovery packages, and medical and food supplies. Solidarity, in this sense, is an instrumentalist discourse.

Reflections and a way forward for Indonesia

Destructive emotions in state-society relations are counterproductive to curbing the spread of COVID-19. The Indonesian government and people should redirect such emotions as part of its anticipative measures and toward building resiliency. Emotion should reinforce a collective motivation to cope with COVID-19, not disrupt social cohesion.

The government should put an end to its policy inconsistency and instead turn to scientific data, translating it into more digestible language so all Indonesians can comprehend and respond to its policies. The government must start to adopt sensitivity to emotion as an approach to policymaking and political communication, not just on COVID-19 but also other issues.

If the government continues to engage influencers to deliver their policies to the public, this effort must utilize knowledge-based information that places people's lives and livelihoods at its heart, rather than its aim to maintain a good public image that only causes ire among its citizens.

As regards multilateralism, Indonesia has taken an active role in ASEAN’s solidarity narrative in proposing the COVID-19 trust fund. Although the future of this mechanism is indistinct due to the ASEAN members’ seeming lack of political willingness, it should maintain the narrative of compassion to fund the fight against COVID-19 through post-pandemic recovery.

On a societal level, the government’s inability to reach its citizens in their everyday lives should motivate civil society to establish civil resilience, because a resilient state and economy lies in the resilience of its citizens. What has been done to this point through altruistic community actions should be highly appreciated; nevertheless, challenges still remain in social stigmatization and civil disobedience. Civil society should continue with compassionate engagement and action, as it possesses the necessary collective emotions and shares the language and understanding.

To conclude, COVID-19 is a global stress test for all governments, societies and people in the world. Emotion plays a Janus-faced role in the pandemic: It causes public distrust and erroneous policymaking processes on the one hand; on the other, it encourages social unity and community engagement among the efforts overcome the multidimensional global crisis toward anticipating a similar challenge in the future. Since no one knows when the pandemic will end and what kinds of long-term impacts it will cause, psychological resilience is tremendously needed as a constructive way forward for both government and society.

***

Research Intern, Department of International Relations, CSIS Indonesia