Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsFight for your freedom: Indonesian online civic space under siege

Cyberspace is the latest arena in the endless battle over freedoms between state and civil forces, and Indonesia's digital democracy warriors aren't ceding a byte without a fight.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

W

hen Joko “Jokowi” Widodo left Surakarta, Central Java, to run for the governor of Jakarta in 2012, the future president was an icon of what Austrian sociologist Christian Fuchs calls “grassroots digital democracy”. With his army of cyber volunteers, Jokowi won the hearts of a budding online community desperate for drastic changes in Jakarta.

The Jokowi Ahok Social Media Volunteers (JASMEV) is one of Jokowi’s largest groups of online volunteers. It took part in his campaigns, though not always officially, for the 2012 Jakarta election and the last two presidential elections.

Jokowi’s political ascent spurred hope for a wider online civic space and the emergence of a digitally empowered civil society that could liberate the nation from the grips of the political elite. This hope could not have been more misplaced.

Shrinking online civic space

Indonesia’s online civic space has, in fact, been shrinking since Jokowi won the presidency in 2014. Digital rights and freedom watchdog SAFEnet has said that more and more people have been charged under the 2008 Electronic Information and Transactions (ITE) Law under the President’s watch, peaking in 2019 with 3,100 cases.

The figure is expected to increase this year, now that the National Police is patrolling the internet to nab those accused of spreading “hoaxes” and “hate speech” about the coronavirus. The police are currently investigating two high-profile ITE cases related to the pandemic. One involves a local punk drummer who peddled a COVID-19 conspiracy theory on his social media accounts, while the other involves a singer-songwriter turned YouTuber who interviewed a fraudulent professor claiming to have produced a cure for the disease.

The situation has gone from bad to worse in recent months, with dozens of activists, journalists and academics critical of the government reportedly falling victim to various cyberattacks. The latest wave targeted an epidemiologist, an NGO and two media outlets – Tempo and Tirto.id – that have been critical of the way the government has been handling the health crisis.

University of Indonesia epidemiologist Pandu Riono cast doubt on the efficacy of the COVID-19 “cure” developed by Airlangga University scientists in cooperation with the Indonesian Military (TNI) and the State Intelligence Agency (BIN), until unidentified hackers took over his Twitter account. The hackers then posted his private photos in an attempt to discredit the scientist.

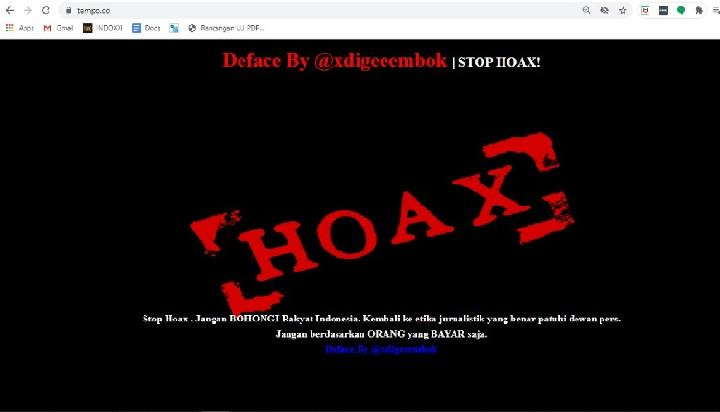

The Tempo website was hacked and defaced after it headlined the cyberattack on Pandu.

Meanwhile, Tirto.id said that two of its articles on production irregularities in the Airlangga-TNI-BIN coronavirus remedy “mysteriously” disappeared. The media outlet then re-uploaded the articles, only for the same thing to happen again.

There is no evidence that the state was behind these cyberattacks. But this does not necessarily mean that the government is not culpable. At least 42 cyberattacks and digital intimidation targeting government critics have been recorded between February and August this year, according to Amnesty International Indonesia, with credential theft the most common form of attack. To date, police have solved none of these cases.

Government is the usual suspect of cyberattacks in other parts of the world. Amnesty International has expressed concerns in the past decade that governments and armed forces are spying on journalists, NGOs and human rights workers.

The first digital attack on a “civilian” target by allegedly state-sponsored hackers occurred in 2010 when Google announced that “a highly sophisticated and targeted attack” on its infrastructure was aimed at “accessing the Gmail accounts of Chinese human rights activists”.

Hacking attacks targeting government critics has become more commonplace since, according to Amnesty.

The 'Jokowi effect': e-participation or e-domination?

There is no doubt that social media has played an important role in raising Jokowi to take center stage in Indonesian politics. There are no grounds, however, to believe that he would be the first in line to defend digital freedom in the country. On the contrary, he could become the first to compromise it, considering the historical context of his political ascent. Here’s why.

A doctoral research by Muninggar Sri Saraswati at Australia’s Murdoch University has found that the 2012 Jakarta election and the 2014 general elections – both of which Jokowi won – marked the rise of the digital election campaign industry in Indonesia. The new industry has in turn created an ecosystem that allowed the emergence of political influencers, widely and derisively known as “political buzzers”. While it is true that Jokowi has genuine volunteers among his online campaign groups, some “volunteers” of his digital army are, in fact, professionals who are paid to manage his online campaigns.

Saraswati argues further that these elections’ social media campaigns were not “autonomous from heavy industry-driven engineering”, and that the growing online political campaign industry has allowed the political elite to “capture social media to safeguard their social ascendancy through competitive elections”.

Indonesia’s cyberspace has since become a highly competitive public arena for the variety of social, political and economic forces in the country. This is why the social media campaign industry is still buzzing even after the elections, with the government reportedly spending around Rp 90 billion (US$6 million) on social media influencers since 2017. Such an antagonistic cyber climate is problematic for Jokowi and his allies, who now control state power and have access to the nation’s information and communications technology (ICT) infrastructure.

The “Jokowi effect” could thus be seen as not just an example of what Fuchs calls “e-participation”, referring to technology enabling political participation by empowering the grassroots but also “e-domination”, in which state actors engage in information warfare or electronic surveillance to dominate or exclude certain groups from online civic space and networks.

Technology does not develop in a vacuum to change how society and the state behave. In reality, as per Fuchs, society also designs technology and its effects are determined by a dialectical loop between the two. In the case of Indonesia, a shrinking online civic space is the current outcome of that endless loop.

Prospects for grassroots digital democracy

Indonesian civil society has long been a sphere of various contesting social and political forces. The state and the oligarchic powers behind it have never taken a back seat in this intrasocietal competition. They can and have formed alliances with incivic forces to weaken civic forces in order to protect their own political and economic interests. The creation of paramilitary group Pam-Swakarsa in the early days of Reformasi is often cited as an example of a state-sponsored uncivil organization.

Sadly, the same pattern has been occurring in cyberspace. The use of “political buzzers” to muddy public discourse on salient social, political and economic issues – the latest example being the government allegedly paying influencers to promote the much-maligned omnibus law on job creation using the #IndonesiaButuhKerja (Indonesia needs jobs) hashtag – shows that this alliance has been extended to the digital realm. And this is occurring concurrently with the misuse of the ITE law and the cyberattacks on government critics.

It is worth noting that while technology may be “designed” by society, it can also constrain as well as enable human action – meaning that the impacts of technology cannot be predetermined and therefore, the possibility still remains for the emergence of grassroots digital democracy that could counter any attempts by the state to control online civic space.

Indonesia has already seen examples of how e-participation, which naturally fights for the interests of the many, can actually force policymakers to behave or not behave in certain ways. One recent example is #ReformasiDikorupsi (reform corrupted), an online campaign to protest the deliberations of controversial bills.

The country’s online civic space may indeed be shrinking under Jokowi administration, but Indonesian civil society can use the very same technology to push back and reclaim it.

***

The author is deputy director of Amnesty International Indonesia.