Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsCurrent state of Indonesian spice trade: We’re not a global leader anymore

Despite the fact that Indonesian soil is an abundant producer of spices, some unsustainable practices have caused the archipelago to lag behind in the spice trade, far removed from its glory days some 500 years ago.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

I

n medieval times, Indonesia was a leading spice exporter, drawing many European explorers to the country. Due to unsustainable practices, unfortunately, the current state of the Indonesian spice trade has largely been a story of missed opportunities.

Sebastian Partogi

The Jakarta Post/Jakarta

Despite the fact that Indonesian soil is an abundant producer of spices, some unsustainable practices have caused the archipelago to lag behind in the spice trade, far removed from its glory days some 500 years ago.

Indonesian Botanical Garden Foundation representative Didiek Setiabudi Hargono says Indonesia is no longer the number one exporter in the international spice trade. Overall, Singapore is currently the world’s number one spice seller, followed by Vietnam, thanks to their ability to produce value-added products.

Indonesia currently faces some different challenges in the global spice trade competition, including low-quality packaging and low prices.

“Low-quality packaging causes a number of spices — pepper, vanilla and quinine — to be damaged during the shipping process. Low commodity prices, meanwhile, make it difficult for our spices to penetrate the premium market segment,” Indrasari Wisnu Wardhana, the Indonesian Trade Ministry’s domestic trade general-directorate secretary told The Jakarta Post by e-mail.

Didiek said biological and environmental factors also contribute to the country’s declining position in the global spice trade.

“Spices require specific types of soil in order to grow. For instance, nutmeg can only flourish in the Eastern [part] of Indonesia. Due to conversions of land into agricultural fields, which started in around the 1970s, our fertile soil availability is now very limited,” he said.

While facing the shrinking of fertile soil, regeneration of spices trees is another crucial problem that needs special attention; Indonesians now have to use synthetic versions of spices like camphor (Cinnamomum camphora), because they have now become endangered species.

“Camphor is extracted from rare trees; it takes hundreds of years for it to crystallize. We, unfortunately, never cultivated the seeds of camphor trees and relied only on those available. This unsustainable practice, which does not pay attention to replanting activities, has driven camphor to near extinction,” Didiek lamented.

He also claimed that certain spice cartels, who play a role in importing indigenous spices already available in Indonesia, also have a hand in causing the value of our spices to decline.

In order to address these problems, Didiek urged the government to designate Indonesia’s top five to 10 spices with high economic value to be cultivated in soil that has been modified to fit their biological requirements.

“The government must designate specific areas in which the spices should be planted according to their biological characteristics. Then, it must determine the total area of land needed to cultivate the spices, based on the quantitative target in which they plan to export the spices,” he explained.

Indrasari said more technology should be developed to create both value-added spices and more superior spice variants — two essential elements needed to be a leading global spice exporter.

“Finally, we should also develop specific brand for our spices through the geographic indicator mechanism. Currently, from Indonesia’s abundance of spices, only four of them have obtained geographic indicators: cloves from Minahasa, North Sulawesi; white pepper from Muntok, West Bangka in Sumatra; Pala from the Siau Island in North Sulawesi and Vanilla from the Alor Island in East Nusa Tenggara,” he explained.

Secrets behind Sriwijaya’s successful spice trade

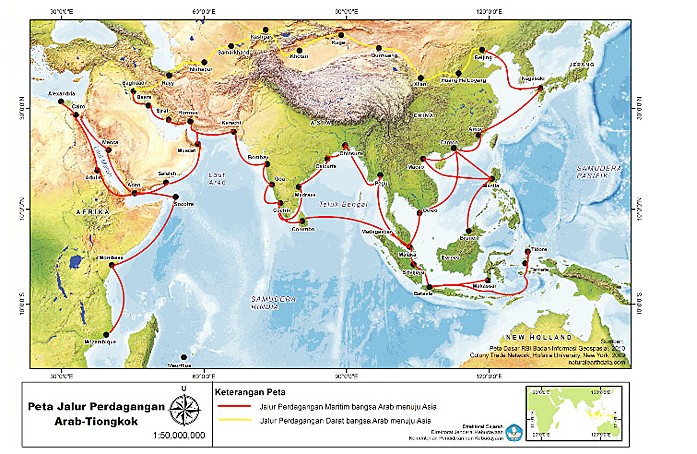

- (-/-)The ancient Indonesian kingdom of Sriwijaya in the southwestern part of Sumatra played a significant role in the history of the spice trail. The kingdom, which possibly originated in Palembang, South Sumatra, rose to power in the seventh century and retained control over the trade of spices — which had grown in abundance in the region — for around 500 years thanks to its strong navy.

Bambang Budi Utomo, a researcher at the National Archaeological Research and Development Center, said for around five centuries, Sriwijaya was the world’s trade hub, where middlemen from Arab and China came to get commodities that had been shipped from the Eastern island of Maluku.

Maluku Island was a home to lucrative spices such as clove, nutmeg and mace. Back then, these and middlemen carefully hid the map of the island from Europeans.

Indonesia’s fertile soil enabled local farmers to maintain the high quality of their spice produce, leaving overseas consumers asking for more.

Pepper, for instance, was also a popular commodity in the spice trade at that time.

“Although pepper originated in India before it was cultivated on Indonesian soil, the pepper grown [here] was somehow hotter than those grown in India. That was why consumers from the Middle East, like Persia [now Iran], and even India itself preferred Indonesian pepper at that time,” Bambang explained.

Camphor was another highlight product from the archipelago. China and Thailand also produced the commodity at that time, but still, traders preferred Indonesian camphor originating in the Barus area of North Sumatra, due to its higher quality.

From all the foreign spice consumers at that time, Indonesian spices attracted the Europeans most as the country is also a home to religious tradition and scriptures.

“Thanks to the middlemen, the ancient spice trade before Sriwijaya had reached Italy before [the birth of] Christ. In around year 75 to 79 AD, the Rome bishop received a gift of 150 pounds of cloves from the Emperor Constantine. In the Old Testament of the Bible, there is a story of Queen Sheba who presents spices as a gift to Solomon,” Bambang said.

He said the Sriwijaya kingdom was able to sustain its hold on the spice trade for hundreds of years as the kingdom had a strong maritime military strategy and technology.

“Sriwijaya made use of the suku laut [ocean tribe] at that time to guard the spice trade in the area. Although their main field of operation was the sea, they were also great warriors,” he said.

This strong military base helped the kingdom guard its maritime sovereignty.

Aside from military strategy, Sriwijaya’s shipping technology also played a vital role in making it a successful maritime hub. They had phinisi wooden boat that helped them navigate the ocean thanks to its design.

Separately, historian JJ Rizal, who runs a publishing company called Komunitas Bambu specializing in history books, said that part of the secret of the kingdom’s survival was its rulers’ strategy in turning financial accumulation into intellectual capital through a sound educational system.

“The port city of Barus gave birth to intellectuals in the seventh century, including Hamzah Fansuri,” he told the Post, referring to the well-known Islamic writer.

“Power was demonstrated not through weaponry, but the grandeur of artistic performances and negotiations,” Rizal said.

It was not long, unfortunately, before the great Sriwijaya started to decline in the 12th century, before its ultimate collapse in the 14th century. By the end of the 16th century, meanwhile, European traders also started to cultivate Indonesian spices in foreign soil, causing local spices to have lost its gloss as commodities.

“There came a time when Sriwijaya became too greedy with the traders and middlemen who came to Sumatra by charging them high taxes. Furthermore, internal conflicts and corruption also contributed to its end,” Bambang said.

Indonesia’s top spice export commodities

- (-/-)Pepper (Piper nigrum)

Indonesia ranks fourth in the global list of pepper exporters, with a total value of US$441.353 and a global export market share of 9.7 percent. Vietnam dominates the list with a total value of US$1.14 billion, followed by India (US$843.85 million) and China (US$453.14 million).

- (-/-)Cloves (Syzygium aromaticum)

Indonesia ranks third in the global list of cloves exporters, with a total value of US$41.57 million and a global export market share of 10.5 percent. Madagascar is on top of the list with a total value of US$149.87 million and a market share of 37.7 percent, followed by Singapore with US$85.69 million and a 21.6 percent market share.

- (-/-)Cinnamon (Cinnamonum burmanni)

Indonesia ranks second in the global list of cinnamon exporters, with a total value of US$94.16 million and a global export market share of 19.4 percent. Sri Lanka is on top of the list with a total value of US$159.11 million and a market share of 32.8 percent.

- (-/-)Nutmeg (Myristica fragrans)

Indonesia ranks third in the global list of nutmeg exporters, with a total value of US$96.67 million and a global export market share of 16 percent. Guatemala is ranked number one, with a value of US$229.08 million and a market share of 38 percent, followed by India with US$107.90 million and a 17.9 percent market share.

— Photos courtesy of Danny Tumbelaka

- (-/-)