Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search results'Subtle Moments': Thriving on a zigzag life

Bruce Grant’s Subtle Moments is not a stationary list of triumphs and big names, but the restless story of recent times told by an articulate hack still gripped by the journalist’s three-letter palsy: why.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

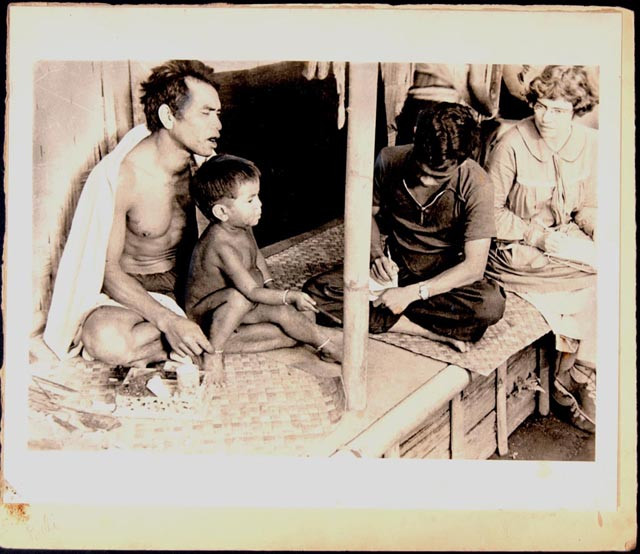

Back in the 1970s there were very few books to guide newcomers to Indonesia.

Texts about the 1965 coup that felled first president Soekarno were mainly academic.

More relevant was American travel writer Bill Dalton’s Indonesia Handbook and the translated works of Pramoedya Ananta Toer, made more exciting because they’d been banned by the second president, Soeharto, although few outsiders could understand why.

Read also: Remembering the legacy of Pramoedya Ananta Toer

Blanche d’Alpuget’s Monkeys in the Dark and Christopher Koch’s The Year of Living Dangerously both featured reporters in Jakarta.

Koch, surprised by success, mused that the public wanted “to see the Australian imagination cross that little bridge into Asia.”

There was another must-read: Australian journalist Bruce Grant’s Indonesia, published in 1964 and revised in 1996, proving its enduring relevance.

Looking back, he describes it as “a young man’s book […] with a brash and critical tone.”

Although now eclipsed by time, events and Elizabeth Pisani’s Indonesia Etc., Grant’s book was once essential for any Westerner trying to wrap her or his mind around this complex, compound nation.

Read also: Examining Indonesia's collective trauma

Now Grant, 92, has released his autobiography, Subtle Moments.

The author is a polymath with the enviable knack of locating himself at the center of major events as a reporter, diplomat, academic, novelist and lover during his “zigzag life.”

Above all he is an informed prose master from a pre-Facebook time when Australian newspapers demanded excellence and editors debated viewpoints with their contributors.

Born in Western Australia, Grant won scholarships that took him to university and a world wider than the wheatbelt, where “space and heat […] the baked earth and lack of rain meant that growth was sparse and low. The hills were worn down.”

As an only son he could have inherited the family farm.

Instead, his inquiring mind lured him into a world of learning and adventure as a foreign correspondent covering the Hungarian Uprising and the Suez Crisis, both in 1956.

He worked for The Age, where his elegant style suited the quality Melbourne broadsheet.

He found journalism “a useful antidote to daydreaming” while deadlines helped sharpen his natural skills.

Covering Southeast Asia out of Singapore he became friends with the late Ananta Toer (they were the same age) and the Indonesian’s nemesis, journalist Mochtar Lubis.

Read also: 12 Indonesian books you should add to your reading list

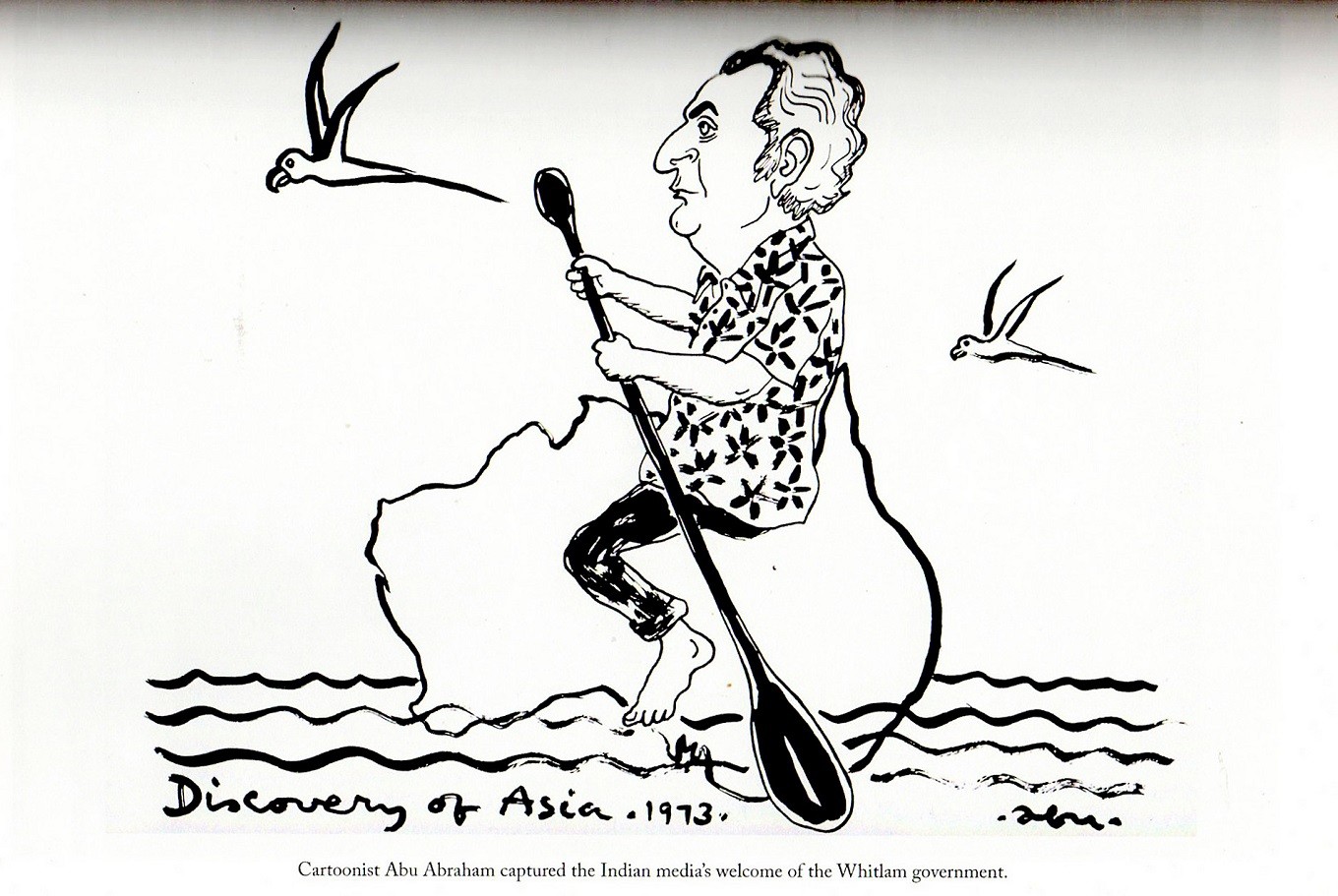

Later Grant was appointed high commissioner to India and was close to the then reformist Australian prime minister Gough Whitlam (1972 to 1975); the two men realized their country needed to refocus its interests from Europe to Asia.

Grant had studied “the sardonic, mocking, fatalistic message of Australian history” so he understood its fears and foibles.

As a public intellectual involved in statecraft, he took part in pivotal debates about Australia’s mates and neighbors.

He cites the joint Australian-Indonesian police co-operation approach to terrorism after the 2002 Bali bombing as a model to follow, rather than the aggressive military action taken in Iraq by the United States with Australia riding pillion.

This is a book that many important Indonesians will rush to read because Grant doesn’t shy away from details about his complex personal life — including painful correspondence from his son about remarriage.

After divorcing his Australian sweetheart Enid Walters he settled down with American poet Joan Pennell, but that relationship became “essentially an intellectual commitment to reforming the world.”

He then wedded Kompas correspondent Ratih Hardjono — they had worked together on assignment in Croatia. She wrote another essential volume, although this time for Indonesians: The White Tribe of Asia, an analysis of Australian history, politics and culture.

When the marriage started to crumble and his wife turned to Islam, Grant sought advice from Indonesia’s fourth president, Abdurrahman “Gus Dur” Wahid.

By then Hardjono was running the State Secretariat and had fallen for a much younger man in the Islamic organization, Nahdlatul Ulama.

After Gus Dur passed away in 2009, Grant wrote a newspaper obituary disclosing the Indonesian leader had asked for details of their correspondence to be kept confidential.

Now Grant reveals the intimate contents of this and other letters: “May God bless us together in finding our different targets in life although with the same aim: To make other people happy while we ourselves are suffering,” wrote Gus Dur.

Grant’s fiction includes a trilogy about affairs between older Australian men and younger Asian women, which start well but end badly.

As academic Alison Broinowski has noted: “The metaphor for the relationship between Australia and Asia is overt.”

Writes Grant: “The novels are hopeful in tone and neighborly in disposition, but in recognition of reality, none has a happy ending.”

In Crossing the Arafura Sea ( 2015 ) the principals are an Australian businessman hoping his nation will “count for something important in its region” while “she is the daughter of an Indonesian mystic whose secret hope is that she will become the country’s president.”

Grant parallels his autobiography, which he subtexts as Scenes on a Life’s Journey, with Australia seeking its international role.

He concludes his nation, first settled by Europeans in the late 18th century and only federated in 1901, is “still a kid” in its relationships with Asia as he said in a recent broadcast.

Adventurers heading to the archipelago who are concerned they might be seduced by Indonesia should consult this splendid book before jumping the next jet to Ngurah Rai.

__________________________________

Subtle Moments

by Bruce Grant

Monash University Publishing 2017

438 pages

(Cartoon from the book of Australian PM Gough Whitlam ‘discovering’ Asia by Indian cartoonist Abu Abraham.)