Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsJung Chang: Bravely challenges China's history

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

C

hinese-born British writer Jung Chang published her landmark book Wild Swans: The Three Daughters of China almost a quarter century ago, but her touching and extraordinary story thrills and deeply moves people until today.

Jung Chang’s book Wild Swans: The Three Daughters of China continues to captivate readers with its story of brutal political turmoil in China over three generations of her family — from her grandmother via her mother to herself.

With more than 13 million copies sold and translated into nearly 40 languages,Wild Swans has become one of the most successful non-fiction books published in the 20th Century.

More importantly, Chang is a first-hand witness and survivor of the cruelty of the Chinese Revolution.

“I chose the title Wild Swans, because I am a wild swan. The Chinese character on the cover of my book means wild swans in Chinese,” she says.

She was given the name Er-hong, or second wild swan, the word “hong” meaning wild swan.

“When I was born, my step grandfather said: ‘Oh another wild swan is born.’ Wild Swan refers to my mother’s name, so I decided to use the word as the title of the book.”

While in the country for the recent Ubud Writers and Readers Festival in Bali, the 65-year-old author looked beautiful and glamorous in her long green silk dress.

“I love what is beautiful. I bought this pretty outfit made by a local designer during my trip to Cartagena, Columbia. Seeing beautiful things makes us happy, and it personally gives me pleasure.”

Beauty and happiness are two words that rarely came to her mind in her early life during Mao Zedong’s Cultural Revolution.

China, at the time, she recalled, was grim and barren, with people only allowed to dress in Mao’s dark blue or grey jackets and pants during winter and white clothes in spring and summer.

“If the Red Guards saw women with long hair and wearing high heels, they would slice them off. Anyone who showed any interest in his or her appearance was condemned as bourgeois and spiritually corrupt,” she recalled.

They did not have public parks or gardens. Entertainment was considered a sinful thing. Books, especially literature, were burned and writers were sent to jail or labor camps, she said.

For Chang, it was impossible to become a writer, as nearly all of them were jailed, sent to labor camps or even executed.

“Thousands of words and stories were cheerfully dancing in my mind while I was doing my labor job. I wrote them on my imaginary paper. With that, I survived the extreme hardship.”

Born in Sichuan province to prominent Chinese Communist Party members, Chang experienced the Cultural Revolution first-hand. Like other teenagers, she briefly joined the Red Guards when she 14.

Her father and mother, both respected and high-ranking officials, openly criticized Mao Zedong’s policies, which led to their imprisonment. Her parents also faced public humiliation with ink poured over their heads. Her father was sent to a labor camp, and her mother was held in detention and tortured.

Chang was exiled to the edge of the Himalayas, where she spent several years as a peasant, a “barefoot doctor” — treating people in rural areas despite only having basic training — and later in a factory as a steelworker and electrician.

After Mao died in 1976, Chang was given a scholarship upon graduating from Sichuan University and working there as a lecturer.

She was the first wave of students allowed to leave China in 1978. She became the first person from China to earn a doctorate in linguistics in l982 from the University of York. Chang met her husband, historian Jon Halliday, in London.

In l988, her mother came to visit her and stayed with her in London.

“I asked her for more details of her past, our family past, because I wanted to be a writer, and my mother knew that I had this unspoken dream.”

Chang said her mother was very brave in opening up her past, her wounds. “During my two years of writing Wild Swans, I felt great pain inside my body and soul, I had a lot of pain, because I consciously opened my wounds — mine and my family’s.”

Trauma caused by the Cultural Revolution haunted her, giving her nightmares, even after she had moved to Britain.

“But after writing Wild Swans, they disappeared,” she says. “During the writing process, the wound gradually healed. Once you open it, you can also heal the wound.”

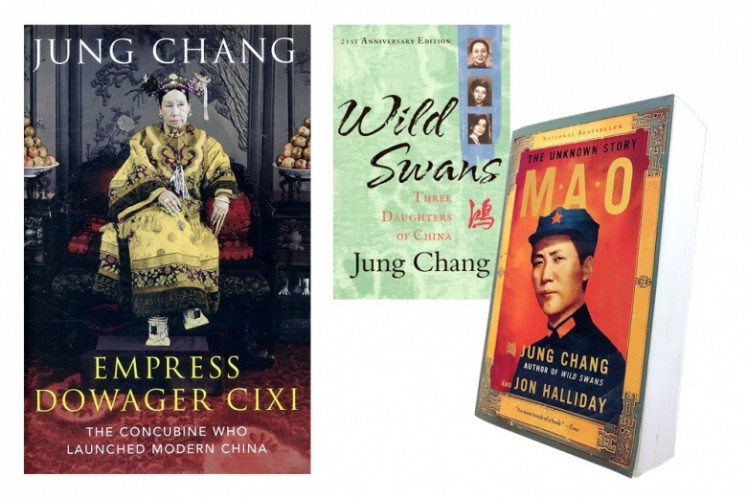

Books by Jung Chang. (Jung Chang/File)Indonesia is no stranger to the writer. Chang and her husband visited the country several times when conducting research and interviews for their book on Mao. They met with numerous people and families affected by the 1965 political upheaval.

“There must be many untold stories to be told. I think most people don’t want to open wounds, you don’t want to see blood, heartache popped up again in your life,” she says. “Women — mothers, grandmothers, sisters — play very important roles in this, because most women would find themselves very strong when they are thrown into harsh circumstances.”

Parents, she said, probably did not tell these traumatic experiences, because they wanted to keep their children away from these taboo subjects.

“Families affected by 1965 must tell their stories to their children, grandchildren and to the people of Indonesia, so they know the real facts — real history as it happened.”

In 2005, together with her historian husband, Chang published her other groundbreaking book: Mao: The Unknown Story — a 900-page account of Mao’s life, the result of 12 years of research. The book shows Mao as one of the most monstrous tyrants of the 20th century.

In the book, Chang and Halliday try to debunk all myths surrounding Mao. “He was not a great leader. He was right there with Hitler and Stalin.”

Mao, she said, dominated her earlier life. “I saw him bringing disaster to my family. Both my father and my grandmother died in the Cultural Revolution, and I saw him turning the lives of a quarter of the world population upside down, yet the world knew very little about him.”

The book also says that Mao was no orator and lacked both idealism and a clear ideology, driven instead by a personal lust of power. “North Korean leader Kim Jong-un is following in Mao’s footsteps. He really learned a lot from Mao,” Chang said.

Chang’s latest book — Empress Dowager Cixi: The Concubine who launched Modern China, centers on the empress, who ruled China behind the scenes from 1861 to 1908. While in China’s history the empress was portrayed as tyrannical and vicious, Chang presents her as a reformer and a feminist.

Chang says the empress actually started the reforms and brought the medieval China into the modern age. The word feminist first appeared in a Chinese newspaper during her reign, Chang pointed out.

“Most history books were written by men. My book on the empress is written from a woman’s perspective.”

Now, Chinese women are striving, and have gone so far as to become scientists, artists, doctors, lawyers and other types of professionals. “Yet, many of them do not know the door was opened for them by the empress.”

She attributes this lack of awareness to a failure to read about history. All of Chang’s books are banned in mainland China.

“It is so difficult to access my books in China, even in the digital era. Internet access is so strictly controlled, and worst of all, the language barrier prevents them from reading books written in English.”

She noted that the present government in China discouraged people from being interested in politics, history, creative writing or literature, instead encouraging them to become successful businessman. Many intelligent people have gone into business as the channel to express their talent, not the arts and literature.

“I love China, I love the people so dearly knowing what they have been going through,” she says.

Her utmost dream now is to translate all of her books into Chinese to allow people to read them. “I also hope my books become a window for the world to see China was like.”