Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

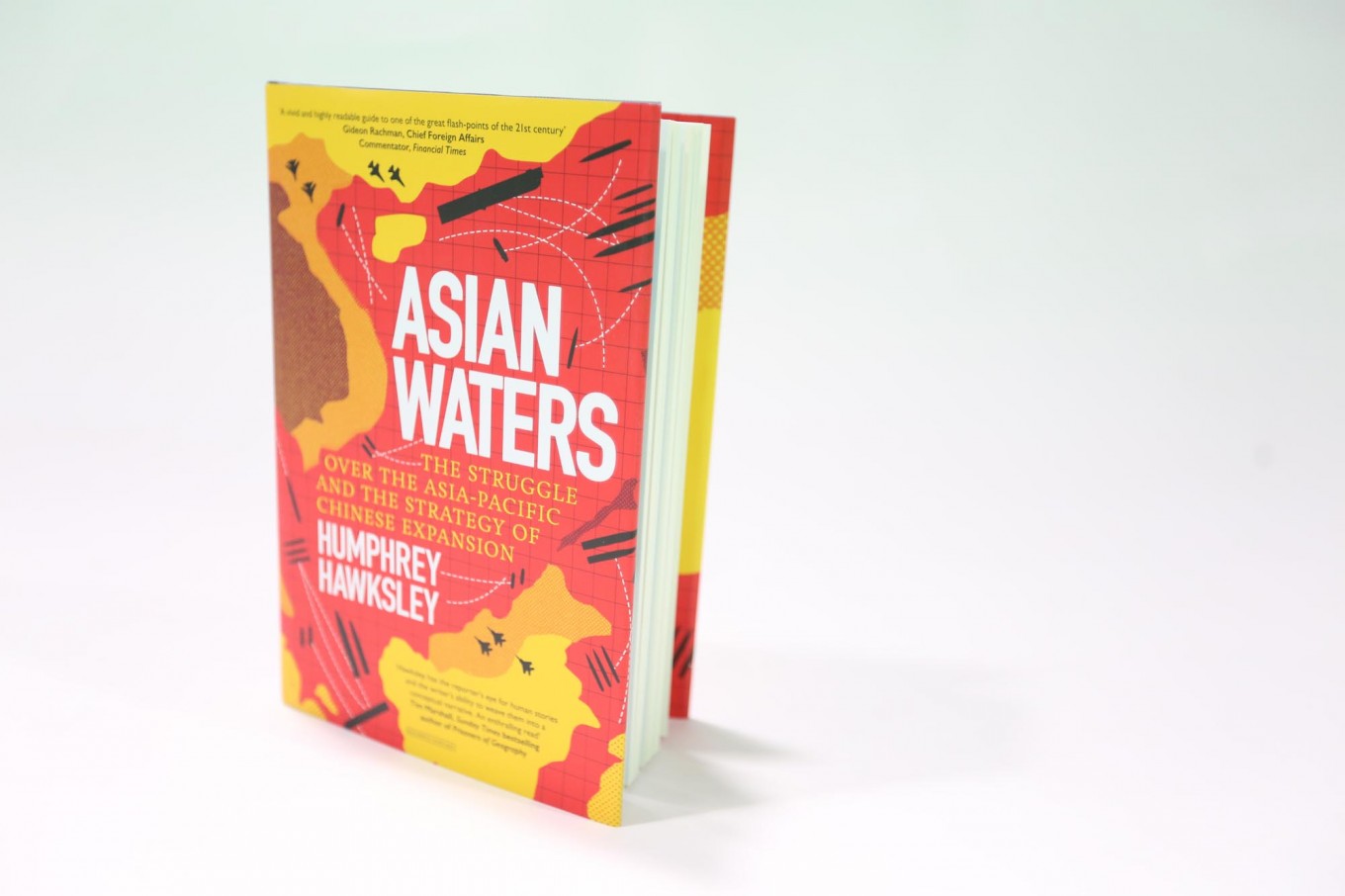

View all search resultsIn 'Asian Waters', Humphrey Hawksley sees Beijing with China’s eyes

"The most common mistake is the failure to see things through Chinese eyes, or indeed Asian eyes."

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

H

umphrey Hawksley is no stranger to Asia. As a foreign correspondent, Hawksley has reported from various crisis points on the continent since the 1980s. The air of acquaintance colors the narrative in his latest book, Asian Waters, published by Bloomsbury and now available at Periplus.

Asian Waters begins with the argument that the continent “is a story about contested water as much as Europe is one about contested land.” The story is, of course, now focused on China and how its rise in recent decades has influenced the dynamic of great power relations in Asia.

With only 264 pages, the book is a condensed read of Asian contemporary history. Asian Waters is divided into four parts, with China’s relations to the respective subregion or country as the anchor: United States, Southeast Asia, South Asia and East Asia.

In an email interview with The Jakarta Post, Humphrey Hawksley answers questions about Asia, now and the future:

In the early part of Asian Waters, you mention that maritime disputes are the defining feature of Asia, as opposed to land in Europe. But you also touch on several issues, such as India-Pakistan, Korean Peninsula and Taiwan, which do not really have anything to do with water. What drives this obviously much-intended inconsistency?

You are right. Some elements like the Sino-Indian stand-off on the Doklam Plateau and Pakistan’s long-running conflict with India over Kashmir are land-based. But, ultimately, power in the Asia-Pacific emanates from the sea. China’s Indian Ocean ‘string of pearls’ ports gives it influence in India’s backyard. Its building of military bases in the South China Sea has thrown out the challenge to the whole of Southeast Asia and from there to the United States and Japan.

The predominant focus of the Asian arms race is sea power, not armies, and for countries like Indonesia and the Philippines with 25,000 islands between them, keeping control of their seas is far higher on the agenda than any prospect of hostile land intervention. This is not the case in Europe, where Ukraine lost Crimea and NATO is actively bolstering defense capabilities in those countries bordering Russia.

It's interesting that you highlight the contrasting perspectives between the US and China, where one sees aggression and the other sees self-protection. What are the biggest mistakes scholars often make when it comes to China, especially when international relations is largely dominated by Western thinkers?

The most common mistake is the failure to see things through Chinese eyes, or indeed Asian eyes. Through Chinese eyes, the first taste its people had of the international order and rules-based trade was from British soldiers on gunboats to sell narcotics and turn the Chinese people into drug addicts. Seen from that view, there is little wonder China wants to secure its sea borders and international supply chains.

When the United States speaks about a free and open Indo-Pacific, Beijing views this as an attempt to stop its growth and, ultimately, force it to become a democratic nation. China has watched with horror as this US policy has been implemented in the Middle East. The more Western thinkers put themselves in China’s shoes, the more common ground they will find.

Read also: Yuval Noah Harari: '21 Lessons' from data, meditation to AI and 'Black Mirror'

China has largely benefited from the US-led international system, but it is now challenging rule-based international order, as evident by its aggressive stance on the South China Sea. What do you think has triggered this change?

Two things, mainly. First, China sees its illegal bases in the South China Sea as part of the essential defense of its southern coastline that was breached in the 1839 Opium War as referenced above. Over earlier centuries, China had secured its northern borders by taking control of regions such as Tibet, Xinjiang, Mongolia and the north-east that used to be Manchuria.

Second, it feels it has not been given the recognition it needs in organizations like the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund and has concluded that the current system is unfair. Therefore, it has set up parallel institutions like the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and earlier the Shanghai Cooperation Organization.

Having said that, China is cherry picking what it will and will not recognize in the international order, because much of it, like joining the World Trade Organization, has been extremely advantageous.

Vietnam and the Philippines are edging closer to China than the US now. Do you think that we are witnessing the slow, but peaceful rise of China's hegemony in the region? That starting with the SCS, China is building its own Monroe Doctrine?

Yes. This is exactly what China is doing, as rising powers like the US, Britain and Japan have done before.

Vietnam and the Philippines have been the strongest proponents against Beijing’s South China Sea claim. Vietnam has fought pitched sea skirmishes and the Philippines took China to the Permanent Court of Arbitration and won. But China’s economic leverage is too great, and many governments in Southeast Asia are realizing that the US will not or cannot offer the all-embracing security they want.

ASEAN, indeed all of Asia, has had many decades of opportunity to bind into a cohesive force aimed at seeing off any hegemon. But it has failed, which is why the Indo-Pacific is now seen as a theater of rivalry between China and the US.

As an Indonesian, I've just got to ask why you dedicate chapters for Vietnam and Philippines but not Indonesia -- especially when your book is titled Asian Waters. I do understand that Indonesia is largely left out of the South China Sea, except for Natuna. But this is the biggest archipelagic country in the world, in which three SLOCs are located. Is Indonesia not enough of a player in the region?

This is a tricky question and I wish I were asking you instead.

Indonesia is the world’s biggest Muslim nation. It is vast in size and lies on the strategic choke points between the Indian and Pacific Oceans. Yet, in global political terms it always seems to punch below its weight.

In Asian Waters I tell some of this story, but Indonesia is not, as yet, directly confronted by Beijing’s South China Sea claim nor, like the Philippines and Vietnam, has it put up open opposition. There are many very good books that concentrate on Southeast Asia and Indonesia itself.

Asian Waters deals with countries around the Indo-Pacific flashpoints and, at present, luckily, Indonesia is not one. It could, though, through size and leadership by example, become pivotal as to how events unfold.

Read also: Book Review: Neil Gaiman revamping old tales in 'Norse Mythology'

Do you think that another full-blown war is possible, or are the stakes too high now due to nuclear weapons and a more interdependent global economy?

A full-blown war is possible, but unlikely. We must remember while Western thinkers, in the comfort of their offices in Washington and London, talk about the Cold War, in Asia that war was very hot. Indonesia bore some of the brunt through the Suharto dictatorship. Full-blown war took place in Vietnam, on the Korean Peninsula, Cambodia and in 1958 President Eisenhower was one signature away from authorizing a nuclear strike against China over Taiwan.

This year’s National Defense Authorization Act in the US Congress is evidence that American policy against China is hardening. Asian governments are bracing themselves for that black and white American dictate: Either you are with us or against us. Asia has been there before and doesn’t want it again. So, not a full-blown regional war, but a proxy war of sorts is not out of the question.

Is the United States losing its grip on Asia permanently or is this just temporary due to the idiosyncrasies of Trump's presidency? If the latter, do you think the next leader can fix all of this?

The US has been losing influence, certainly since 2001 when its concentration became focused on the Middle East. President Obama attempted to claw it back with his 2011 Pivot to Asia which China viewed as a hostile policy of containment. Since then, China has built its South China Sea bases, set up embryonic parallel institutions, captured the global imagination with its Belt and Road Initiative and used economic leverage to dilute Asian loyalty to the US. Some of this was inevitable, given China’s rise. Some was because America took its eye off the ball. Beijing is now planning towards the 2049, the centenary anniversary of the Communist Party taking power.

Against that backdrop, Trump is an interlude and Beijing will deal him in the most pragmatic way that will allow it to achieve its goals. It is useful to remember that China is geographically located within Asia. The United States is not.

You close your book by calling for a peaceful resolution for all the disputes in the Asian Waters. But in a time where China freely bends international law to its own will, the question is: how?

China would lose badly in any economic or military war, which in turn would risk deflation of the Communist Party’s myth of supremacy. Civil unrest could then usher in the end of the Chinese dream. Beijing knows this and is careful about how far it pushes. The key problem is that there is no mechanism to enforce international law, which is why China has gotten away with its South China Sea bases. (How could the US and China contemplate military confrontation over a fishing reef when there’s North Korea and a global financial crisis to sort out?)

On its own, the South China Sea dispute resolution would only be a temporary bandage. But settlement there could lead to wider, rolling negotiations that end up writing a new rules-based order reflecting the world view less through American and European eyes and more through the eyes of China, Indonesia, the rest of Asia and the wider developing world. (kes)