Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsShort Story: Home Sweet Home

What seemed familiar about the place she grew up in was often lost on her.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

L

ike her name, Mega, which means a girl who is like the clouds, Edemi Mega loved the idea of flying, suspended somewhere, grateful for the little respite even though she was nowhere near the orbit of finding an answer to where her life was headed. She would figure out what to do next when she landed. In the meantime, she watched cairns of clouds giving way to achingly blue skies out there, the patches of green and blue anchored below telling her little about where she was.

Hours later, when the familiar necklace of mountains and paddy fields shimmering in the sun came into view, and as the plane approached Soekarno-Hatta International Airport, she shut the window flap tight, regretting her decision to come home. What seemed familiar about the place she grew up in was often lost on her. She had never understood it and probably never would.

As she wended down the glass-covered aerobridge, she felt the familiar tropical heat creeping up her skin despite the chill of the air conditioning. Too much sun in this country, she thought. Not being able to stand the sudden glare of sunlight, she fished out her sunglasses from her handbag and put them on quickly.

But it wasn’t just the heat that she hated.

By the time she walked over to the luggage collection belt, it was only just starting up. From behind black flaps spewed out contents of life stories safely tucked inside each and every suitcase and parcel box — waiting to be picked up, then unpacked in a hotel or home, the story continuing from where it left off. Swept along by the bustle of passengers coming and going, she could feel the magic she always felt at the airport — teasing with promises — where you couldn’t be sure what there was out there to embrace or how you would alter your life story with an inculpable stroke when you stepped into the busy node. It fascinated her how people from different destinations all over the world would converge in the same spot, as she was at this moment in time, yet never to meet again.

Her face fresh without a trace of fatigue, in her white skater dress that barely reached her knees and a pair of casual flats, she stood, her arms folded, watching for more contents spilling out onto the belt, then looping around the winding path and disappearing into the black flaps.

The unpicked luggage spewed out yet again like some reincarnations till the gods reached out to lift them out of their sorry plights. She scanned the faces of the passengers with whom she had spent the last 13 hours in the air from Munich to Jakarta via a stopover in Singapore. She had connected with the rest, following a short hour-long flight from Berlin, which had been her home for the last eight years. When she first left Indonesia, she hadn’t bought herself a return ticket.

She could have continued to call Berlin home had it not been for her mum who rang her up one fine Sunday evening after she had revelled with some friends in an open-air karaoke in the quirky Mauer Park. In her commanding tone, she told her to return home, at once, then for once, pleading with her when the former failed to work.

A stroke had crippled her dad. The family jewelry business was mired in a muddle of mess after their second uncle (her mum’s second brother) fought over control of the business with her dad who cofounded the business with her grandfather. Ibunya’s side of people, as her dad used to say. Edemi wasn’t keen to know more. She had walked out of her life back home because she didn’t want any part in the family drama. Life was much more fun-loving when she was younger.

Her parents were not as busy and they would often take her on short getaways to different parts of the country.

You can walk out of your life here for all I care was her dad’s last words to her on the night before she had left for Berlin. As the jewelry business lifted off the ground, Edemi couldn’t put a finger on why her genial dad would evolve into a monster of sorts, always picking on her, even though she had to admit that she could be willful and stubborn at times. I don’t want to disappear like you and everybody else into your own tiny life and not live it. It was her parting shot then.

When she spotted her suitcase with a rainbow ribbon tied around the top handle emerging around the corner toward her, Edemi hesitated for a moment before she pulled it off the belt.

Setting it on the ground as she gripped the handle upward to pull it along, she headed away from the exit that was steps away. She wasn’t ready to embrace what was out there. She found herself a seat in a corner not far from the belt, unsure about what to do next. It wasn’t lost on her that what the next step could change her life, irreparably.

Where she was seated, she took in the moving belt with the unclaimed pieces of luggage moving along like a joyride. There was a constant stream of people arriving at the belt, waiting for those things that were a part of their lives to appear on it. Once they grabbed their things they moved on with their life in tow to the next destination. Why had it become so hard for her to do the same, just like everybody else?

Resting her luggage flat on the empty seats, she scrambled the numbers to unlock it.

What she had on was no match for the artificial cold as she searched the luggage for her cardigan. Cobbled inside were a few pieces of summer clothes. She did not think that she would stick around long enough. Besides her large bag of cosmetics and toiletries, she had brought along a half-read novel, a story set in Berlin. She had left it unfinished intentionally, not wanting to break the bond with her Berliner life.

After putting on her cardigan, Edemi sat herself down beside her luggage. The hard plastic of the seats was no more welcoming than that found elsewhere. It was not meant for one to linger longer than needed, much like Tegel Airport in Berlin where she first boarded.

Built as a hexagonal complex to move passengers in quick time, all it took were a few brisk steps from the taxi stand to the ticketing counter, right past the security counters into the departure gate and out onto the aerobridge in a zip.

“Mbak, is there anything I can help you with?” A voice, politely helpful, broke her thoughts. Edemi looked up to see a lady in a smart suit, her name — Fatin, Airport Concierge — proudly emblazoned on her jacket.

“No, no,” Edemi replied hastily. “Saya baik-baik saja [I’m good]. Thanks for asking.”

“My pleasure,” she replied helpfully, a brilliant smile bracketed her face.

As she watched the lady walk away, Edemi could feel her heart racing hard. A wallop more to her chest would have rent her heart asunder on the spot. Too much sun, too much risk, she muttered.

Too willful maybe.

While wanting to stay defiant, Edemi regretted at the same time she had brought the pot (marijuana) stash along. The idea, conceivably irresistible before, now sat hollow in her heart. But how could she have resisted it? A puff was all it would take to suspend her somewhere, make the homecoming easier and the stay more pleasant.

She worked her memory for the penalty — How many grams for conviction? Do they still shoot people for drugs?

Perhaps it was all meant to be. The inconsolable unconscious part of her wanted to be caught and deported. This way, she did not have to go home and see her dad, in a state she imagined was no less broken than her granddad was a week after she came home from a holiday trip. Her granddad used to be a jockey before venturing into the family business. Edemi was taken on horse rides in the leafy enclave of Tangerang when she was a child. In a way, it was the experience of horse-riding at the spine of Tangerang, an area increasingly assaulted by urbanization that made Edemi wish to live somewhere else, out in the countryside where she could canter on the horse, not just watch a steeplechase on the turf club.

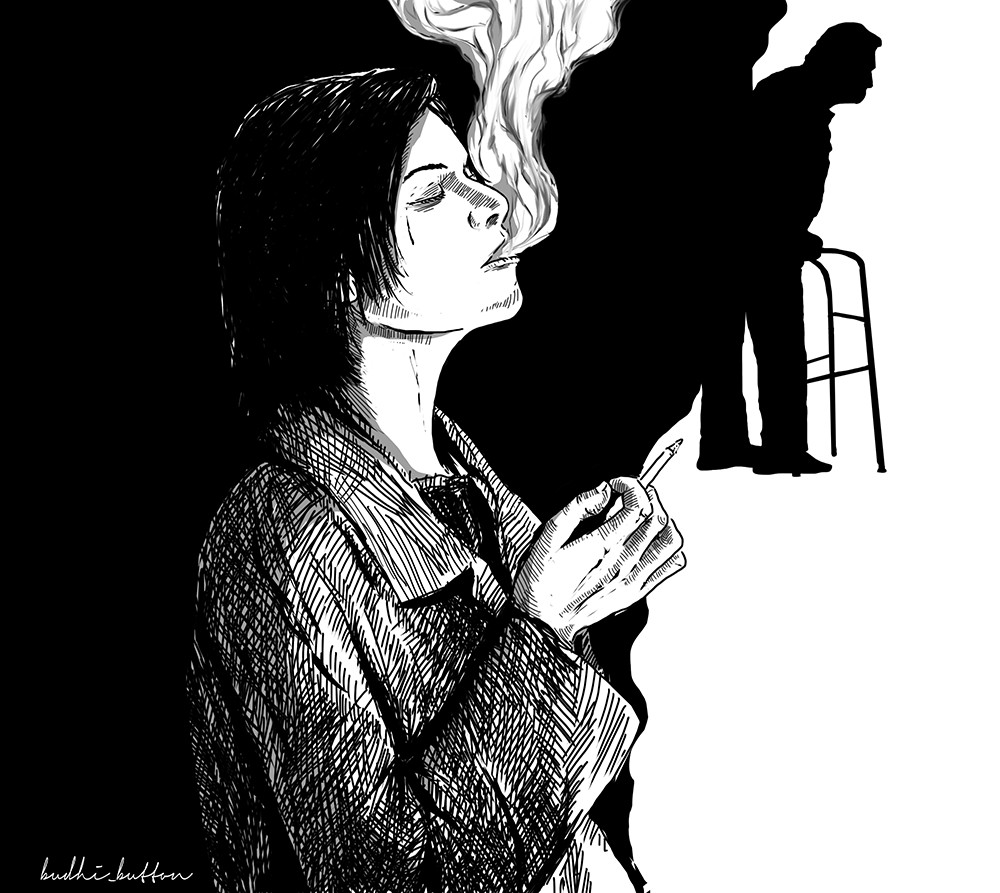

After the stroke, her granddad’s hair turned sullen white overnight, barely able to speak, mouth looped sideways, eyes retreated into somewhere that was not quite him anymore. For the rest of the two years he was alive, he was mostly confined to the bed in his study on the ground floor of the house, because he could no longer make his way up the stairs to his bedroom. Now, Edemi could not reconcile the image of her dad — who always thrived on picking a good fight — now sitting defeated on the edge of the bed; the dare in him leaking into a kind of resignation or surrender. At this thought, it saddened her that it had come to this: Wouldn’t it be such a fake to make up with her dad at his most feeble?

Standing her luggage on the ground, Edemi pulled it along as she headed toward the washroom. Just a puff, perhaps that would clear the head, then she would know what to do next.

Latching the door behind her, she lifted the luggage onto the toilet seat and unscrambled it as she searched for the pocket penknife in flap pocket. Using the blade, she carefully unstitched the seams behind the flap and took out the small packet of pot stash concealed there.

With the seams torn, Edemi suddenly felt a sense of relief. Now, she could no longer conceal it back where she put it, so she would have to dispose of it.

The right thing to do.

She rolled a little of the stash deftly on the tobacco paper and lit it, filling her lungs to the brim before she exhaled the anguish and all that was locked inside her.

As the high kicked in, Edemi felt it was somebody else’s experience she was having, like an actor in character — smoking pot, living life.

Edemi was vaguely aware of the rapid knocks that came raining hard onto the door, as she sat slumped on top of her luggage above the toilet seat. Her mind had descended into a swirl of cotton.

“Madam, can you please step out of the cubicle?” A voice, firm and steely, ringed on the other side of the door.

Edemi could not make out whether it was a woman or man standing outside. Moments before the rattling stopped and the latch gave way, there was a quiet few seconds where her mind trailed off. Then, just like that, the seconds were gone: the door sprang open and there were faces staring at her before she got dragged out of the hole. Edemi finally realized why she loved flying — you never really knew what there was to embrace until you embraced it fully.

***

The writer is currently working on a novel in his spare time with mulish determination and self-doubt. His stories have appeared in the Quarterly Literary Review Singapore, New Asian Writing and Azuria Australia, among others, and has been made into a short film, as well as appearing in educational textbooks.

________________

We are looking for contemporary fiction between 1,500 and 2,000 words by established and new authors. Stories must be original and previously unpublished in English.

The email for submitting stories is: shortstory@thejakartapost.com

We are no longer accepting short story submissions for both online and print editions. New submissions to shortstory@thejakartapost.com will not be published.