Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsTwo female photographers juxtaposed in Paris exhibition

An exhibition shows the work of Martine Franck and Marie Bovo, presenting the contrast between portrait and still life, as well as black and white and color.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

A

gnes Sire, artistic director of the Henri Cartier-Bresson Foundation, is focusing on the work of two female photographers who also produce moving images. The two parallel exhibitions opened on Feb. 25 and will run until May 27.

The work of Martine Franck (1938-2012), a Belgian photographer whose black and white photography is featured in the “Collections Gallery” section, is always sober and classic. Daughter of a Belgian banker, she used inherited money to establish the foundation two years before her husband’s death in 2004.

Face à Face (Face to Face), also the title of one of her books, mirrors the direct, sympathetic attitude toward her subjects that was characteristic of Franck’s discreet photography. Franck, who was married to Henri Cartier-Bresson in the latter part of his life, took time to portray people, whether they were artists, fellow photographers or elderly people living in charitable institutions. These portraits were a mixture of commissioned work and personal research. Although rather timid, she nevertheless rapidly summed others up, never “stealing” an image against the will of her subjects.

Franck once said, “A portrait is always a renewed encounter. I am nervous just before a shooting, then gradually tongues start to loosen up. What I am after is to capture the light in the eye, the movements and the receptiveness and concentration – just when the model remains silent.”

'Elderly woman at La Maison de Nanterre nursing home, 1978.' (Magnum Photos/Martine Franck)Franck’s eye was trained by studies in history of art in Madrid and in Paris. Travels with her wealthy collector parents, Louis and Evelyn Franck, and younger brother Eric broadened her horizons, as they enjoyed painting, sculpture and encounters with people and landscapes. While writing her final paper for her studies at L’école du Louvre in Paris, she realized that she was drawn to photography rather than writing about art. A cousin gave her a simple Leica to begin learning photography.

After leaving two other photo agencies which she had helped found, Franck became a member of Magnum Agency, one of only a few women in the organization. Franck and Cartier-Bresson's daughter urged her to do so, despite Franck’s reluctance to be labeled the wife of one of the founders. Franck often traveled to Ireland, where she followed travelers and made a film about their lives. She accumulated many portfolios about the most varied subjects.

Even after being diagnosed with bone cancer, she courageously continued working, between her appointments for painful treatment, until her death in 2012 at the age of 74.

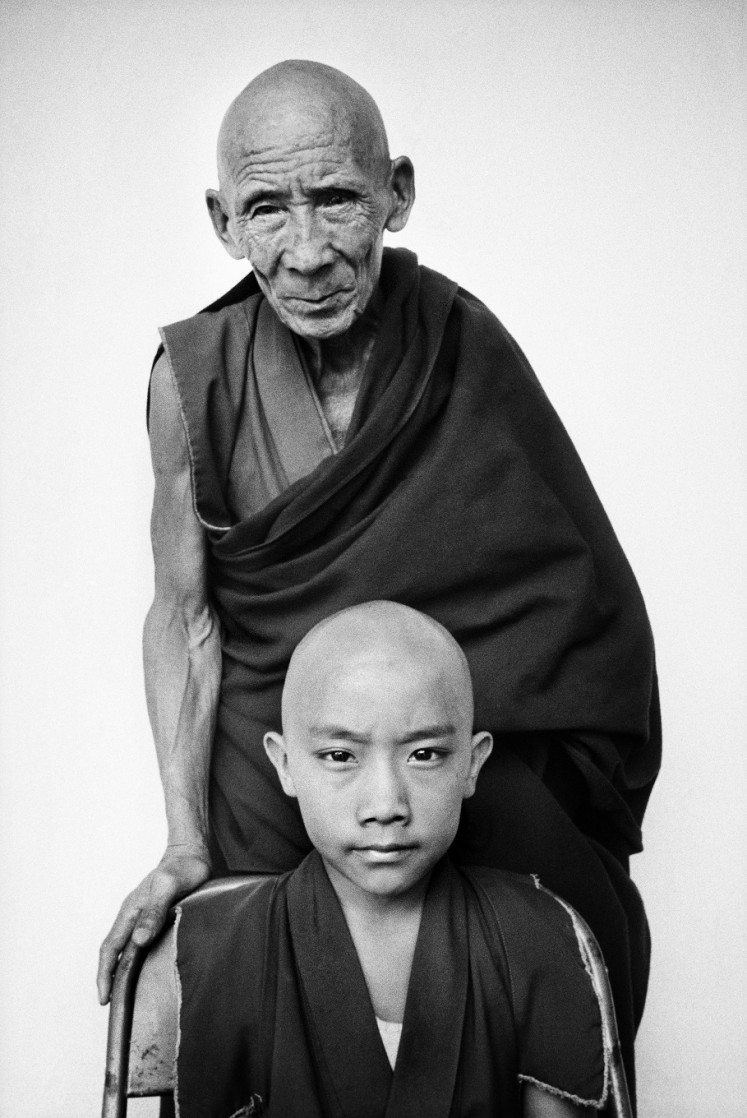

Martine and Cartier-Bresson were fellow seekers of Tibetan Buddhism, as the 1996 portrait of Tenzin Tosan Rinpoche with his monk tutor Gen Pagdo at Ratu Monastery in Karnataka State, India, in the show testifies. This was one of a series Franck undertook while traveling, after Cartier-Bresson ceased to travel outside Europe and concentrated on drawing while tending to their daughter’s education – and later their grand-daughter’s.

'Tenzin Tosan Rinpoche with his tutor Gen Pagdo, Rato Monastery, Karnataka State, India, 1996.' (Magnum Photos/Martine Franck)Marie Bovo was born a generation later than Martine Franck in Alicante, Spain, in 1967. She is now 53. In contrast to Franck, she mainly lives and works in Marseille – or occasionally across the Mediterranean in North Africa. Neither her grandparents nor her mother and Italian father, second-generation immigrants to France, could read or write. The tradition in her family was first and foremost an oral one where she listened to family anecdotes. Art, books and painting were absent, but a photograph in her grandmother's room of a Virgin Mary sculpture cradling the dead Jesus Christ on her lap, captured her attention early on.

During her workshop at Arles Photo Festival 2017, she said that when she was a child, she wanted to become a sculptor because of the poignancy of that image. Sculpture seemed to her as realistic as portraying a living human being. After primary school in Marseille, where her art teacher encouraged her to draw and gently guided her to study art history in high school, Bovo began her study of plastic arts and literature in Marseille. It was only when a friend gave her a simple camera that she began to learn to take photos, develop prints and capture light on film.

Influenced by her studies of art history, Bovo realized the importance of light in photography. She was drawn to capturing images at dusk or in early morning hours when light began to outline shapes and influence sensations. Bovo wished to portray the people who lived in impoverished surroundings in Marseille but realized that she had to take time to gain their confidence.

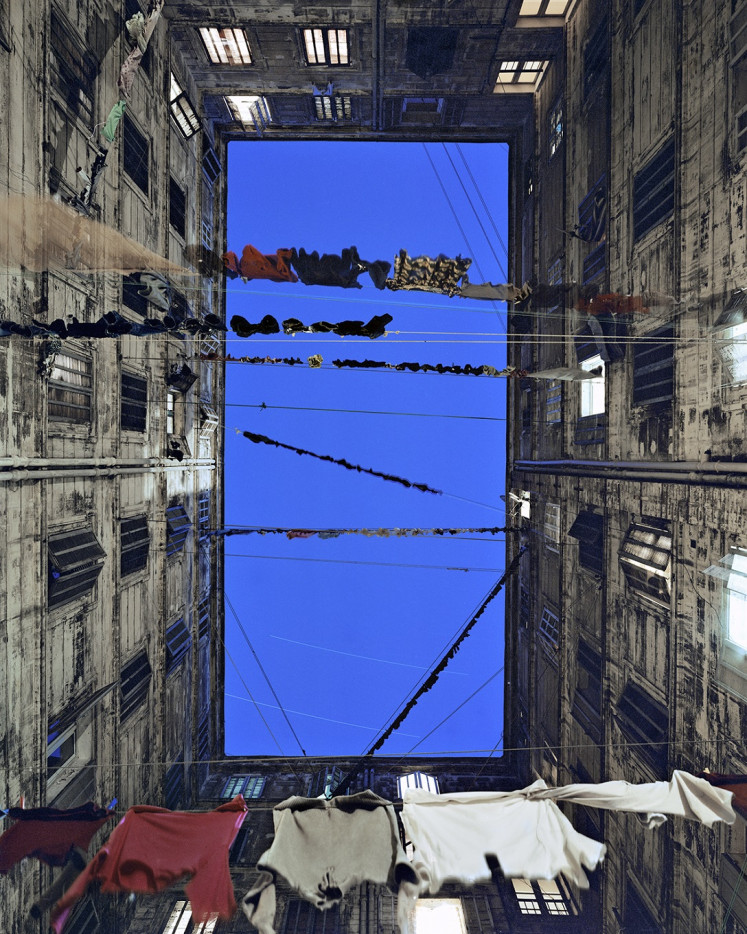

'Interior courtyard, Marseille, April 2009.' (Courtesy of the artist and kammel mennour Paris/London/Marie Bovo)A friend of hers lived in one of the common courtyards in Marseille where immigrants were crowded into small flats. This urban habitat fascinated Bovo but the inhabitants did not welcome a stranger with a camera barging into their lives. The photographer began introducing herself gently into these communities, often quite close to the harbor in Marseille. Her photography is in color, but she never introduced a voyeuristic aspect to portraying people living in slums as she usually restrained herself to documenting the evidence left behind by human lives.

In her color series, Marie Bovo emphasizes light in nocturnal scenes, as well as the architecture of old buildings, many of which were originally fine buildings situated on formerly grand avenues sloping down toward the harbor from the surrounding hills of Marseille. Bovo, holding her camera, often either looks down into the shafts of the courtyards or upwards toward the light streaming down to hint at the sculptural contours of buildings, courtyards and urban landscapes.

Bovo also takes photos horizontally, straight out of open windows of buildings she inhabits momentarily, like that of a female friend in Algiers, Algeria. Here the photographer spent some time on the other side of the Mediterranean. Otherwise she points her camera into inner spaces like former restaurants with remaining tiles to remind visitors of a more glorious past.

Bovo once noted that, “For art, night is essential. Our eye meets a strong barrier, the color black, which we cannot overcome, a withdrawal of light. It means accepting that certain things escape the eye like the voyeuristic and exhibitionist and basically violent impulses of contemporary society to try to push back the night by using harsh light.”

Later in her photographic experience, she traveled by train to Africa, Russia and Northern Europe. Always influenced by nocturnal experiences, the travels inspired her to come up with a photographic journal in the form of a book called Nocturnes. Bovo’s exhibition entitled "Nocturnes" presents 35 large-format color prints with two films of her travels. In Russia, the vast white spaces framed images with basic colors that cut across the purity of snow, while making it possible for Bovo to meet the people along the tracks. Otherwise, she has studied the different shades of grey which she encountered in her travels by studying Gerhard Richter’s paintings.

It was this fresh and innovative approach to color photography that caught famous Parisian modern art gallerist Kamel Mennour’s eyes. He immediately acknowledged her extraordinary talent and encouraged her work and research in Paris and in London, where he also has a gallery, in addition to introducing her to the art world in general.

Bovo’s personality seems always to be happy and inquiring, like when she follows a stream of milk winding down the cobbled streets of old Marseille, capturing the obstacles and stories so characteristic of the ancient harbor city. The video captures the daily adventure of living in a huge metropolis where life is never a simple story but teems with surprises. Over a century ago, Marseille also beckoned to a young Henri Cartier-Bresson but in black and white images. However, that is another story. (wng)