Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

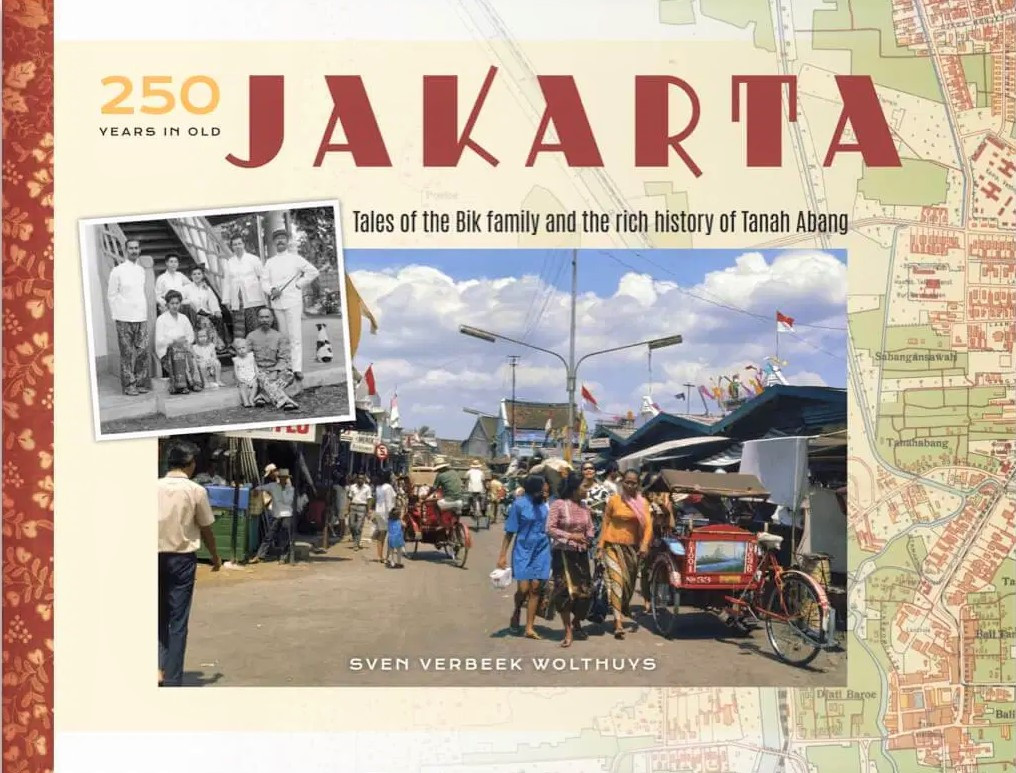

View all search results‘250 Years in Old Jakarta’: Tracing history, family and the Big Durian

Tanah Abang may be known by many as Jakarta’s transportation hub and home to Southeast Asia’s largest textile market. But for Dutch author Sven Verbeek Wolthuys, it is a walk down memory lane.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

L

ong before Tanah Abang in Central Jakarta was known for textiles and traffic jams, the district began life as a camp for the troops of Sultan Agung of the Mataram Kingdom – in 1628.

The first settlement in Tanah Abang dates to around 1650 and the market itself opened in 1735.

In 1863, a Dutch businessman named Jannus Theodorus Bik purchased a piece of land in Tanah Abang, which included a country house and most of the land of, and properties in, Pasar Tanah Abang.

Now, more than 150 years later, a descendant of the Bik family has successfully chronicled the history of his family, along with the records of Tanah Abang, over the last two centuries.

Titled 250 Years in Old Jakarta, the book is the brainchild of Sven Verbeek Wolthuys, who has been researching the history of Jakarta for more than 30 years. Though he was born in the Netherlands, he moved to Sydney, Australia, with his family in 2007.

During a visit to The Jakarta Post’s office, Wolthuys said he wrote the book as a result of the encouragement of people around him.

The journey started 30 years ago, when his grandmother told him stories about her childhood in Tanah Abang.

“After she passed away, I tried to find all the missing links, like where they lived in Tanah Abang, what the house looked like and its eventual fate. I started to research and discovered that my family used to live in Tanah Abang,” he said.

He was also interested in the history of the Arab and Chinese traders who settled there.

About eight years ago, Wolthuys was asked to speak about the history of Jakarta on tours of Tanah Abang. Around that time, he also created the Lost Jakarta page on Facebook, where he published historical photos and stories. The page now has more than 29,000 likes.

When he joined a tour of Tanah Abang as a speaker in 2015, he said many tourgoers asked him when he would write a book. He replied that he had never thought of it.

The book, which is available exclusively on lostjakarta.com, explores both the history of the city and this history of Wolthuy’s family. Family photos can be seen alongside historical maps. One chapter chronicles the rapid change of Tanah Abang after Indonesian independence.

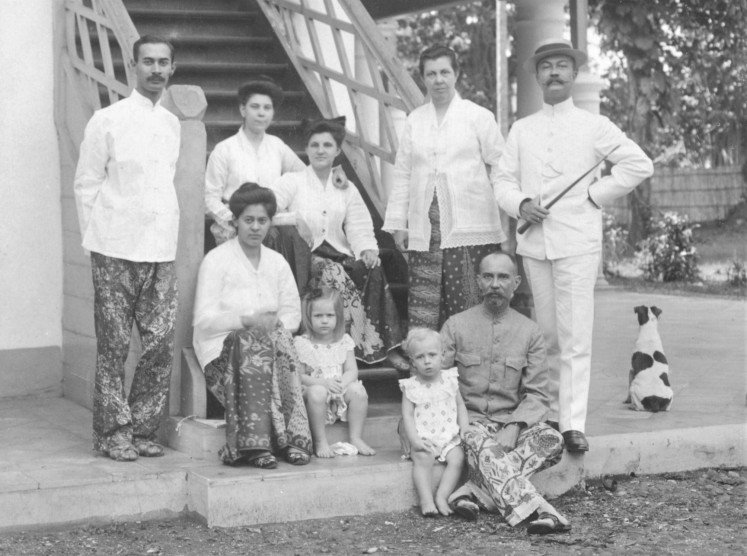

Generations: A photograph of the author's grandmother and great-great-grandparents in front of the Tanah Abang Bukit house in 1908. (Courtesy of Lost Jakarta Publishers/-)The Bik family first came to the city, which was then known as Batavia, in 1816. A 59-year-old grain merchant named Jan Bik left Amsterdam with his wife and nine children to find a better life after being appointed a civil servant in the East Indies.

Jan’s eldest son Adrianus Johannes Bik was the first to make the trip. He began working as a draughtsman for Caspar Georg Carl Reinwardt, the founder of the Bogor Botanical Gardens in West Java. Reinwardt also invited Jannus Theodorus, Adrianus’ brother, to work for him during his expeditions in 1819.

Jannus Theodorus, known as Dorus, was also active as a teacher. In 1819, a young boy named Saleh Sjarif Boestaman became one of his students. He was later known as Raden Saleh, one of Indonesia’s most prolific painters.

Dorus was one of the most influential members of the Bik family, not only for his estates but also for his connections to the Van Riemsdijk family, where the Tanah Abang estate likely came from.

After his passing in 1875, Dorus’ 9-year-old son Willem Frederik Butyn inherited his father’s wealth of 19 million Gulden, which Wolthuys claims is worth some US$250 million at today’s prices. However, Willem Frederik died five years later, and the fortune was divided between 32 of Dorus’ nephews and nieces.

Balancing family and historical tidbits was the biggest struggle in writing the book for Wolthuys, who said that, at one point, he wondered whether he was writing a book about the history of Tanah Abang or about his own family.

After finishing a chapter on Tanah Abang, he read it again and found it “boring”, in his own words, as it only discussed buildings and streets.

“There was no personal aspect in there, someone suggested that I start with – and that’s what I did – introducing how my family arrived in Indonesia, how Tanah Abang developed until my family settled there,” he says.

“And then there’s a period of nearly a century where my family was an integral part of Tanah Abang, and after my family left, Tanah Abang developed further.”

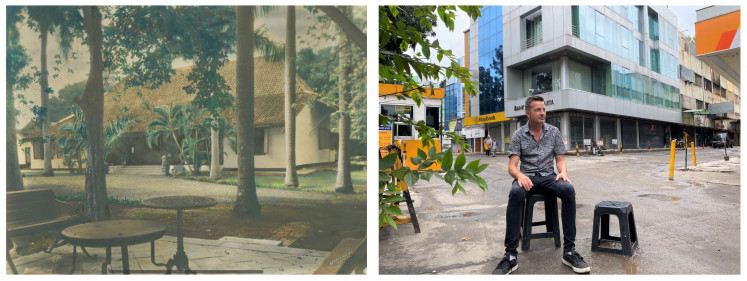

Then and now: The Tanah Abang Bukit house as seen in 1930, and the book’s author sitting in the same spot in 2020. (Courtesy of Lost Jakarta Publishers/-)Wolthuys first visited Jakarta in 1995, and he thought Tanah Abang had changed a lot compared to his grandmother’s recollections.

The change from 1995 to the present day, he says, was probably more drastic than the changes from 1945 to 1995.

“In 1995, I could walk from Taman Prasasti or Jalan Abdul Muis to the pasar [market] and there were probably 40-50 houses and buildings left from World War II or 19th-century buildings, but that all has mostly disappeared.

“The biggest transition, apart from the pasar of course, has been that Tanah Abang was a residential district. People used to live there with gardens and driveways, and that has changed. It is now very much commercial,” he said.

In doing his research, Wolthuys compared aerial photographs of Tanah Abang in 1945 with Google Earth images from 2018, where he found that about 98 percent of the buildings from 1945 had disappeared.

“What I do hope, of course, is that the remaining two percent at least remains – something to tell the people of Jakarta about the history of Tanah Abang.”

Regal: Paleis te Rijswijk, now known as the State Palace, in 1947 (Courtesy of Lost Jakarta Publishers/-)Wolthuys is already researching his next book. He said he was fascinated by the district of Menteng for its historical buildings and heritage.

However, he said the book on Menteng could be the last, as the research could take three to five years on its own. Plus, finishing the first book was quite exhausting for him, so the one on Menteng might be where he draws the line.

“I had hopes – but it’s probably too late already – but in 2027 Jakarta will commemorate 500 years, and I thought it would be great if by that time there’s a whole series of books on Jakarta over the past 500 years,” he said. “[The year] 2027 might sound far away, but I can only maybe write two books in that time.” (ste)