Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsArnold Ap: Papua’s lost cultural crusader gets long-delayed recognition

Arnold Ap fought to preserve his people’s culture, celebrating it through music, humor and joyous performance. He paid for it with his life. Now, almost forty years after his controversial death, one of Papua’s most important cultural icons is being recognized by the wider public.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

N

obody knows precisely how it all ended, but we know what came after. On April 26, 1984, the body of Arnold Ap was found riddled with bullets and stab wounds on a beach near Jayapura. He had been mysteriously detained for four months. His family was in hiding, his friends forced into silence or exile and his legacy lost in a blazing inferno.

His crime? Singing and keeping his people’s culture alive.

Now, almost four decades after his controversial murder, one of Papua’s most important cultural figures is being recognized by the wider public.

“For his time, he was a groundbreaking curator and artist,” said Ayos Purwoaji, a curator and researcher. “He moved beyond the boundaries of the museum, which was unusual for his contemporaries.”

Through his work as an anthropologist, curator and bandleader in the highly popular group Mambesak, Arnold Ap celebrated Papuan culture at a time when such expressions of indigenous pride could lead to arrest, intimidation and death. His short but storied career was marked by persistence, unusual but effective cultural tactics and, above all, a boundless love for his land and people.

Before long, though, his story turned into one of tragedy, violence and exile.

Celebrating Papuan identity

After a violent and hotly contested military operation, the Indonesian government under President Sukarno seized control of West Papua from Dutch rule in May 1963.

Human rights activist Carmel Budiardjo wrote in 2008 that not long after the seizure, a “huge bonfire” was erected in the main square of Jayapura. Symbols of Papuan life, including cultural artifacts and Papuan flags, were thrown into the inferno, while over ten thousand Papuans were brought in from the valleys to watch the ceremonial burning of “their colonial identity”.

Soon, indigenous political activities were banned and a “political quarantine” was imposed. In 1969, after an internationally controversial referendum, Papua voted to join Indonesia.

This was the world Arnold Clemens Ap saw as a young man. Then a geography student at Jayapura’s Cendrawasih University, his interest soon shifted to anthropology and Papua’s diverse cultures. He was a talented guitarist and a gifted storyteller, but most of all, he was a tireless scholar and a charismatic leader of his peers.

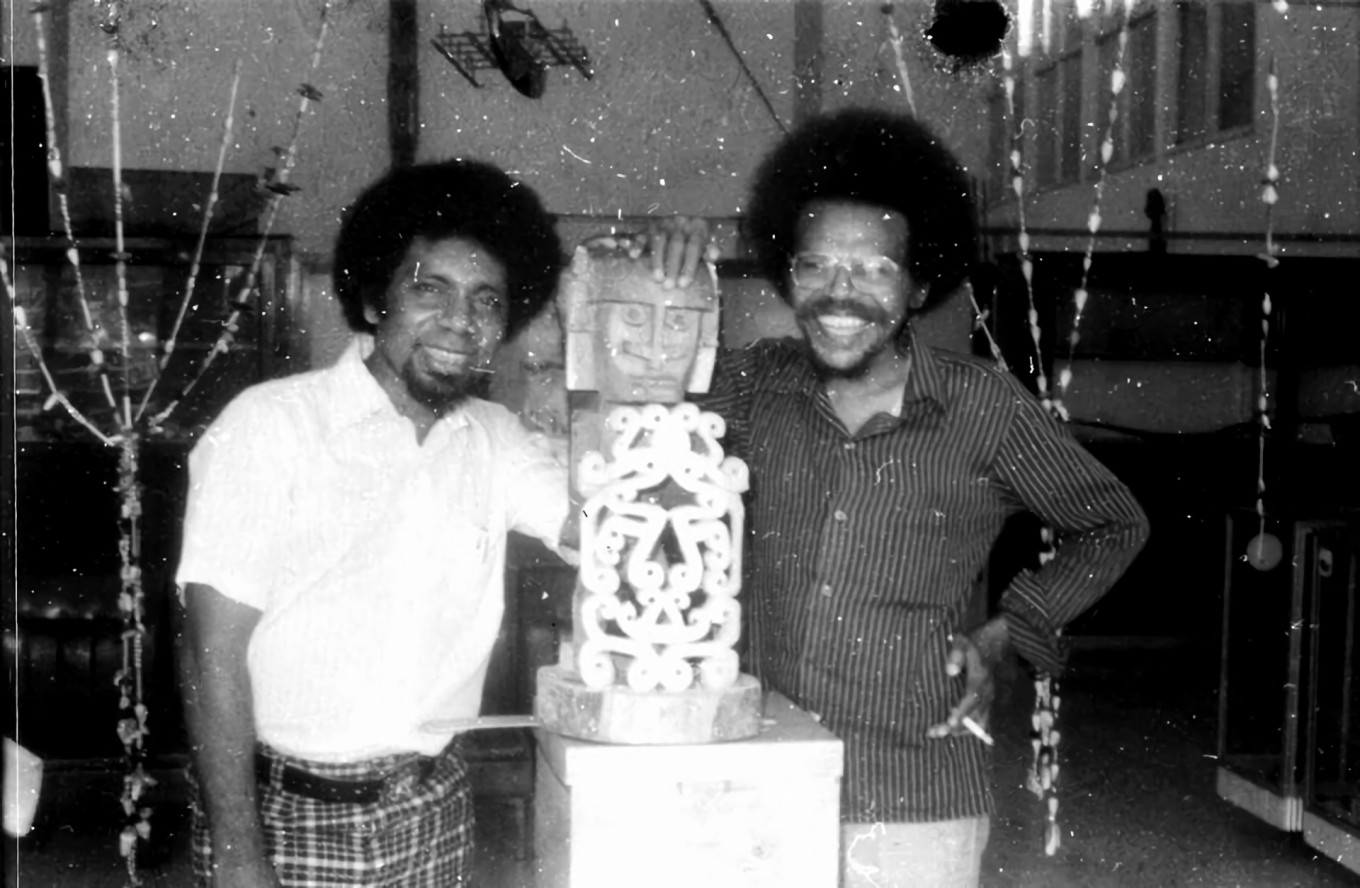

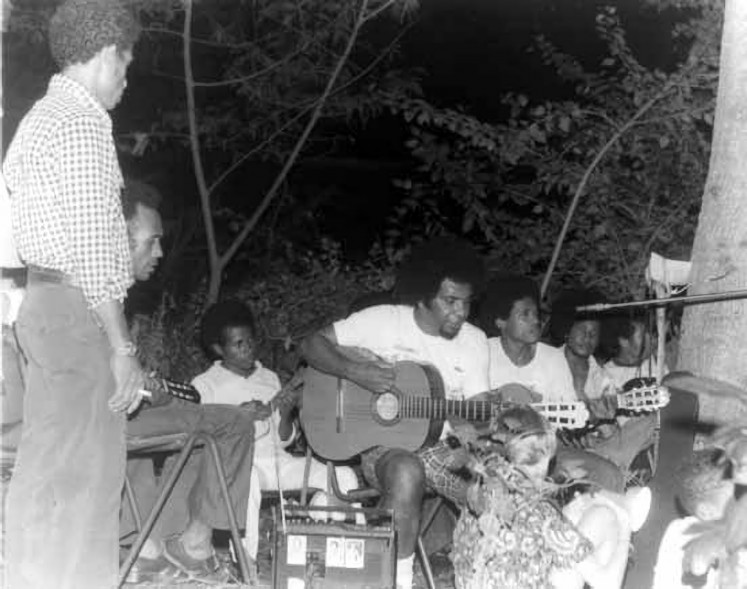

When Cendrawasih University opened its cultural museum, Loka Budaya, in 1973, Ap was quickly hired and eventually became its curator. In these early days Ap would depart to far-flung corners of Papua, sitting down with village elders and documenting each place’s traditional music, dance, sculpture and folklore.

“He would document everything,” said Ibiroma Wamla, an anthropologist, “local words of wisdom, lyrics and poetry, the process of building traditional houses and even how they make traditional boats.”

His findings impressed his peers. His house in Abepura became a hub for budding artists, weary travelers and Papua’s burgeoning intellectual scene.

On Aug. 5, 1978, he and Sam Kapissa gathered their peers and formed the band Mambesak, meaning bird of paradise in his native tongue, Biak. Along with original compositions, they would perform some of the traditional songs Ap documented in his wanderings, along with stories of Papua and its people. Then, Ap would recount traditional jokes and humorous stories common in Papua’s highlands, before a joyous song and dance routine broke out again.

Their popularity were bolstered further by their weekly radio show, Pelangi Budaya dan Pancaran Sastra, broadcast every Sunday on a local Jayapura station and hosted by a rotating cast of Mambesak members.

Beginning in 1978, the group recorded seven albums, released regularly and distributed through the then-novel medium of cassette. In 1981, with the support of Cendrawasih University, they also published four songbooks documenting traditional music from various parts of Papua.

Perhaps wary of the political climate at the time, Mambesak was rarely overtly critical in its music.

“Their songs would talk about protecting the forests, preserving traditional culture and even something seemingly trivial like imploring Papuans to keep eating sago,” Wamla noted.

That is not to say, however, that their work lacked a political dimension.

Sago, a traditional starchy root vegetable, was traditionally the staple food of many Papuans. The transition to eating rice, a West Indonesian staple that was foreign to Papua, symbolized to many Papuans a loss of connection with their ancestral roots and culture. By writing a song about sago, Mambesak managed to criticize what its members saw as Papuan cultural erasure by simply singing about food.

Ap’s work in this vein was both groundbreaking and wildly popular. But before long, it landed him in hot water.

Death of a performer

Papua, at the time, was a hotbed for separatist movements. Guerilla fighters from the Free Papua Movement (OPM) ravaged the countryside, ensuring a steady military presence and a tense atmosphere. By the 1980s, the tensions were high enough that the military began tracking down independence sympathizers in cities.

Mambesak, with their popular performances and albums, were a natural target. “Soeharto’s regime thought Arnold Ap and Mambesak were dangerous,” Ibiroma said. “[They thought] these cultural performances could gradually revive Papuan nationalism.”

Mambesak, and Ap in particular, were accused of fomenting revolutionary fervor. The authorities cracked down hard.

On Nov. 30, 1983, a day after Mambesak performed at the West Papuan governor’s hall, Arnold Ap was detained by members of Kopassandha, a precursor to the Army Special Forces (Kopassus). The rector of Cendrawasih University, once Ap’s most ardent supporter, quickly dismissed him as curator because of his arrest “on suspicion of subversive activities”.

For the following four months, Ap’s fate remained a mystery. His peers leaked news of his arrest to international media, leading to sporadic protests and condemnation that was quickly stamped out by authorities and national media. Perhaps wary of reprisals, Ap’s family were smuggled out of West Papua in February 1984. Rumors began circulating that Ap, along with four other detainees accused of sympathizing with the revolutionary cause, were being tortured and maltreated.

As Carmel Budiardjo wrote in Inside Indonesia, on April 14, 1984, he was seen on the grounds of Cendrawasih University being escorted by an officer. Soon after, the authorities announced that Ap had escaped from prison with four other detainees and that a regional manhunt was underway. He was labeled “extremely dangerous”, and authorities began pushing for Ap to be sentenced to life imprisonment or even death.

On April 21, an officer unlocked Ap’s cell door and ordered him and the other detainees out. The special forces then reportedly drove them to a coastal base camp, where one detainee escaped and saw the rest of the story unfold from his hiding place.

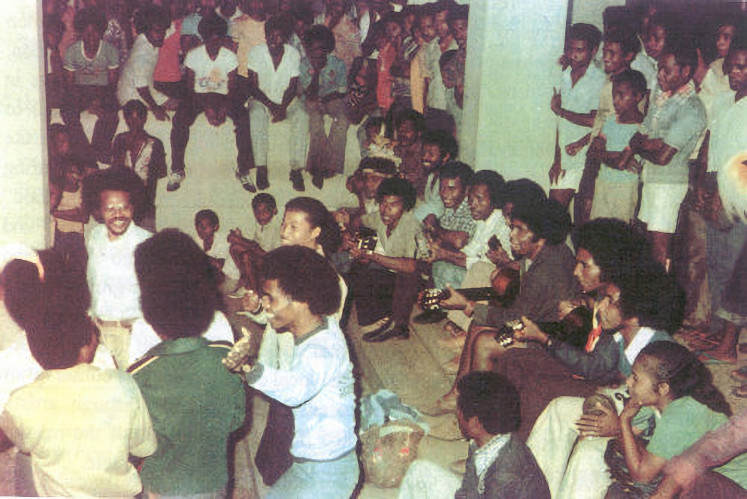

Mambesak performs in 1981. Arnold Ap (center, playing guitar) was the band’s leader and inspiration. (Personal collection/Courtesy of Ayos Purwoaji)Eddy Mofu, a member of Mambesak, was, according to the detainee, struck on the head, stabbed in the neck and thrown into the sea. The others were told to swim out to a boat and eventually found shelter in a cave. A few days later, Ap emerged from his hiding spot to urinate. He was soon surrounded by elite troops and gunned down.

According to Budiardjo, there are conflicting accounts of what happened next. Some say he died. Others claim he made it to a nearby hospital, where he asked a nurse to deliver his wedding ring to his wife in exile.

A legacy of fire

“After Ap was murdered, a source informed me that military officers burned down his house and a majority of his archives,” Ayos said. The remaining members of Mambesak were either driven into exile or intimidated into silence. Ap’s family remained in hiding in Papua New Guinea for a while, before seeking sanctuary in the Netherlands, where they remain today. Ap’s legacy, it seemed, had been lost to history.

But his story and work somehow persisted. Journalist George Junus Aditjondro, who traveled extensively in Papua and struck up a close personal friendship with Ap, wrote about Mambesak in his book, Cahaya Bintang Kejora. Scholars like Frank Hubatka studied his curatorial approach, Cendrawasih University eventually republished his cassettes, and friends and family members held on to their archives and memories in private.

“It was a bit difficult to piece together an accurate timeline of his life and work,” said Ibiroma. “A lot of former Mambesak members were still traumatized and would refuse to be interviewed. The archives were scattered and incomplete, and a lot of writings were lost. We had to approach each former member one by one and slowly recreate his story.”

Ibiroma’s research eventually caught the eye of Ayos, a co-curator in this year’s Jogja Biennale arts exhibition. “Our focus this year is on Oceania as a sociopsychological zone that encompasses East Indonesia to Hawaii,” Ayos explained. “This region doesn’t just share similar cultural genes but also common social problems and solidarity.”

Their attention naturally turned to Papua, where a group of scholars at Cendrawasih University were hard at work reviving Ap’s legacy. “Beyond his accomplishments as a musician, he was also Papua’s first true curator,” Ayos said. “His curatorial approach blended art and cultural activism, moving away from art museums and confined exhibitions. Instead, he expressed his findings through music and performance.”

Collaborating with Cendrawasih University as a “docking program” partner, the Jogja Biennale aims to finally celebrate Ap’s legacy as a pioneering curator in East Indonesia. “In Indonesian curatorial studies, people like Ap are neglected,” Ayos said. “The history of Indonesian art is dominated by Javanese curators. Having people like Arnold Ap in the narrative will expand our horizons.”

Annual vigils still mark the dates of Mambesak’s formation and Arnold Ap’s death. “Arnold Ap is a cultural icon, but he was also someone who united the Papuan people through music,” Ibiroma said. “For him, no culture was superior or inferior. Each culture in a country completed and enhanced the others.” If Papua was to be truly a part of Indonesia, Ap believed, then its culture needed to thrive, not be suppressed.

“I think he deserves respect,” Ibiroma said. “And the government must admit that they were wrong to kill him.”