Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsNowhere else to go: Safehouses for abused women

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

W

ith domestic violence cases soaring during the pandemic, safehouses have become the last refuge for abused women. However, they struggle to carry on.

This was Sasa’s life for several decades: She was routinely beaten, threatened and sexually assaulted by her husband. She was forcibly isolated from her friends and family. Her income was limited to such a degree that she would go to bed starving; that is, when the unceasing barrage of violence paused and she managed to get some sleep.

At the age of 52, she decided she had had enough. Something had to change, but where would she begin?

“After I managed to escape, I needed somewhere safe to figure out my next move,” she said, speaking on condition of anonymity. “That’s why safehouses are necessary. Without their existence, people in my position wouldn’t even contemplate fighting back against violence.”

Safehouses are the unsung heroes that fight back against Indonesia’s epidemic of domestic violence. Providing counseling, legal aid and mediating discussions with family members, they are a place of refuge for victims of violence and their families alike.

Some are well-oiled machines with secure funding and close relationships with government agencies. Others, though, are small, community-run houses staffed by volunteers and run more on hope rather than expectation.

Both have struggled since the pandemic. As violence against women and children soared, government services collapsed and COVID outbreaks loom large, their travails paint an increasingly worrying picture.

A worrying trend

“When the pandemic started, we were left in the dark,” said Defirentia One, director of Yogyakarta-based safehouse Rifka Annisa Women’s Crisis Center. “Hoaxes were everywhere, health protocols were incomplete and tests were still very expensive. If a client comes to the safehouse, how can we make sure they’re not a virus carrier?”

This put Rifka Annisa between a rock and a hard place. Operating since 1993, it has built a reputation as one of the country’s most trusted safehouses. But when the pandemic forced private enterprises and government agencies alike to move their activities online, Rifka Annisa found a concerning trend.

“We decided to open a hotline for victims of domestic violence and abuse, and our clients increased by 300 percent,” One revealed. “We would handle an average of 300 cases a year. In 2020 alone, we handled almost 1,000.”

The numbers speak for themselves. Recent data by the National Commission on Violence Against Women (Komnas Perempuan) revealed a shocking rise of violence against women during the pandemic.

In 2020, Komnas Perempuan received over 2,300 reports of violence against women, a 68 percent increase compared to the previous year. The trend shows no sign of abating. In the first half of 2021 alone, Komnas Perempuan received some 2,500 cases of violence against women, more than the entirety of 2020.

As layoffs became depressingly common and business shuttered their doors, economic woes pushed many families over the edge. However, another factor is the sudden, changing roles many had to take on in their daily lives.

“Many clients told us they struggled to help their children navigate remote schooling,” One revealed. “They had to accompany their children and work from home while under the threat of layoffs. The situation became untenable.”

Daily lives were upended and calls started flooding in from outside Yogyakarta, where Rifka Annisa is based.

“People from all over the country were calling us, complaining that government services for victims were closed,” One said. “We tried referring them to our contacts in their area, but it didn’t always work.”

Many victims, she said, simply had nowhere to go. As the pandemic raged on, government-run shelters for victims of domestic violence simply stopped operating. Reports began filtering through that government-run hotlines were overwhelmed with cases, while government agencies hurriedly reshuffled their decks after sudden, massive budget cuts.

“Services were shuttered and became cumbersome because the government allegedly diverted their funds and resources to battling the pandemic,” One said. “But these cases are consequences of the pandemic. This is part of the problem.

“It was a collective shock to the system. Even other community-run safehouses in Yogyakarta were closing.”

Whoever could still operate had to pick up the pieces.

“During the pandemic, government agencies in Surabaya and East Java were afraid to take on new clients and cases,” said Wahyu “Yayuk” Laili, shelter coordinator at Surabaya-based safehouse Yayasan Embun. “So, if any victims needed shelter, they sent them to community initiatives like us, practically sweeping the problem under the rug.”

Something had to give and safehouses like Rifka Annisa eventually relented to the ever-increasing demand.

“We can’t fight against their emergencies,” One said. “If a client is kicked out of their home or their safety is threatened by staying at home, they need a shelter. A pandemic doesn’t change that.”

Changing times

As safehouses were forced to forge on, smaller shelters like Yayasan Embun had to make do with what they had. Operating since 2012 out of a once-rickety house in Surabaya that was refurbished, it has always been a community-run enterprise staffed by a tight-knit crew of volunteers.

As economic realities choked them, though, many found themselves wavering.

“Our volunteers stopped participating one by one, and now we’re only staffed by two people and their spouses,” said Joseph Lato, Yayasan Embun’s founder. “We’re working day jobs to support our operations. Finding employees is easy, finding dedicated people is difficult.”

At one point during the pandemic, Yayasan Embun’s small building housed 15 abuse victims at the same time, many of them children as young as 12. This put a massive strain on the small-scale operation.

Even more established safehouses like Rifka Annisa struggled. Frustrated by the ever-changing social restrictions and confusing health protocols, the Rifka Annisa team drafted its own health and safety protocol. Its staff was required to wear masks and protective gear at all times and offices were reorganized to allow for outdoor counseling sessions.

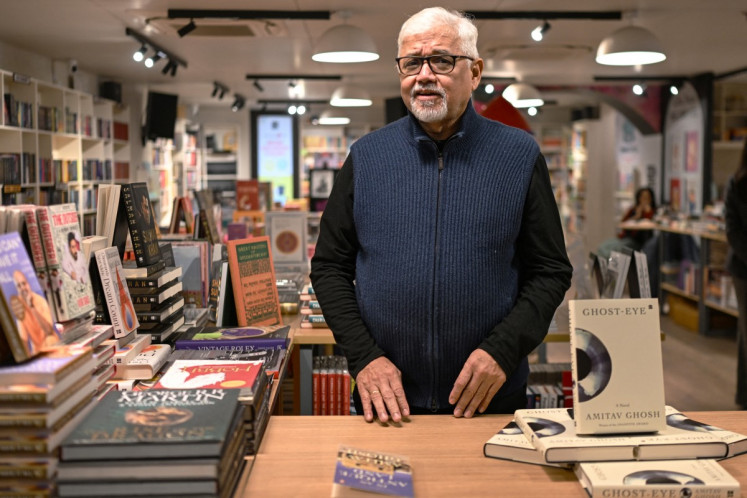

Keeping safe: Counseling at the Rifka Annisa Women's Crisis Center is now mostly done outdoors. (Rifka Annisa Women's Crisis Centre) (Personal archive/Courtesy of Rifka Annisa Women's Crisis Centre)Despite all this, danger still slipped through the cracks. Many clients escaped from abusive households with only the clothes on their backs, meaning they didn't have the economic resources to access proper COVID-19 screening and tests.

“There was a case where we found out too late that a client came from a red zone,” One revealed. “She lived in Jakarta but was abused in Yogyakarta and escaped with her baby. No family would take her in. This was dangerous to our staff, but she had nowhere else to go. What could we do?

“Clients also come to us while they are depressed and under a lot of stress. So, they’re in a bit of a mental fog. It doesn’t come to mind that they still have to wear masks and follow all these complicated procedures. We can protect our staff, but we can’t control our clients.”

The risks and consequences are obvious. Lato revealed that Yayasan Embun once had to implement a total lockdown after he and his entire family were stricken with COVID-19. Rifka Annisa also had to struggle with occasional COVID-19 outbreaks, forcing its staff to go into quarantine and halting most of its services.

Systemic failures

The consequences of Indonesia’s systemic failures during the pandemic have hit Yayasan Embun hard.

“One and a half years ago, we took in a 14-year-old girl who was pregnant. She had been repeatedly sexually assaulted by her father, who was then found to be suffering from a severe mental illness.”

To make matters worse, a neighbor who “came in like a white knight” sexually assaulted the girl as well, resulting in her isolation from her family.

“Because her father had neglected her for so long, she didn’t have a NIK [citizen’s identity number],” Lato revealed. “Because of this, when she entered our care, she couldn’t access public health services or even take PCR tests.”

Tragically, the child lost her baby because of a miscarriage. But when Lato attempted to take the child’s neighbor to court, the man “reportedly had a stroke” and returned to his family home — right next to the child’s own home.

“Now, she’s frustrated,” Lato sighed. “She can’t come home because it would only make her trauma worse. She can’t go to school because it's taking so long to sort out her NIK. She doesn’t know what to do.”

Lato rightly points out that slow civil services and law enforcement hamper any effort to heal and rehabilitate victims.

“Civil service is a human right,” he emphasized. “Even if she doesn’t have a NIK, she should be able to access health care and schooling. Victims should be given priority.”