Discrimination haunts ex-Gafatar members

Years after the Fajar Nusantara Movement (Gafatar) was disbanded after being accused of blasphemy, its ghost continues to be a source of controversy

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

Y

ears after the Fajar Nusantara Movement (Gafatar) was disbanded after being accused of blasphemy, its ghost continues to be a source of controversy.

“We are stigmatized as if we are terrorists,” Adam Mirza, a former member of Gafatar said in a public discussion at the Indonesian Legal Aid office in Menteng, Central Jakarta.

Robi Sugara, a researcher at the Indonesian Muslim Crisis Center, said Gafatar is a non-violent organization that is easily misunderstood as a radical group because its founder was involved with several radical movements.

“Ahmad Musadeq, who founded Gafatar in 2011, was involved in a radical separatist movement called the Indonesian Islamic Nation. He was also involved in Al Qiyadah, a sect in which he claimed himself as the new apostle,” Robi said.

“However, before establishing Gafatar, Musadeq had undergone a philosophical transformation and renounced his apostolic claim.”

Adam Mirza said although the founding of the organization was based on a spiritual journey, its movement focused on social activities such as blood donor events and agricultural development.

“In Kalimantan, the Dayak community gave us land to develop. With our technology, we succeeded when farming on peatland and turning brackish water into fresh drinking water,” Adam said.

He claimed the organization had recruited 52,000 members in 34 provinces in less than four years.

Following its rapid growth, Gafatar faced resistance in many places. In April 2014, Aceh Ulema Council filed a report accusing three Gafatar leaders of blasphemy. Abdul Fatah, Gafatar’s leader in Aceh, was sentenced to five years in prison, while five other members were sentenced to three years’ imprisonment. Gafatar’s Aceh branch was subsequently disbanded.

Gafatar faced discrimination in other places across the country, which led to the organization being disbanded in August 2015.

“We decided to stop using the name and moved to Kalimantan to form an agricultural community under the name Negeri Karunia Tuhan Semesta Alam [God’s Blessed Country of the Universe],” Adam said.

“At that time Kalimantan was the place where we faced the least persecution,” he added.

In December 2015, Rica Tri Handayani, a doctor from Sleman, Yogyakarta was reported missing. She allegedly left to join Gafatar and the police found her in Mempawah, West Kalimantan.

Subsequently, the Indonesian Ulema Council (MUI) conducted a study on whether Gafatar’s movement was blasphemous toward Islam.

“Their recruitment practices involved people disappearing. Not only Rica, but also other people,” Ali M. Abdillah, a member of the MUI research team, said.

“A civil servant applied for early pension, sold his land and moved to Kalimantan to join Gafatar. A female student in Yogyakarta said to her parents that women do not need to wear the hijab,” Ali said, referring to past cases.

“These sudden and extreme changes in belief caused anxiety to the recruit’s families,” he said.

He also said Gafatar believed Muslims do not need to pray five times a day nor fast during Ramadhan.

“Gafatar is also known to mix Christian and Jewish teaching with its spiritual practices,” he said.

Regarding this, Adam said Gafatar members read the Torah and Bible as a supplement. There was also continuous interfaith dialogue among its members.

“But it does not mean we made a new religion by mixing them up. I am still a Muslim,” he said.

Regardless, MUI concluded the study by releasing a decree that Gafatar’s teaching was blasphemous and appealed to Muslims not to join the movement.

“In the decree we also appealed to Muslims not to discriminate against the members of Gafatar. We appealed to the government to guarantee their wellbeing,” Ali said.

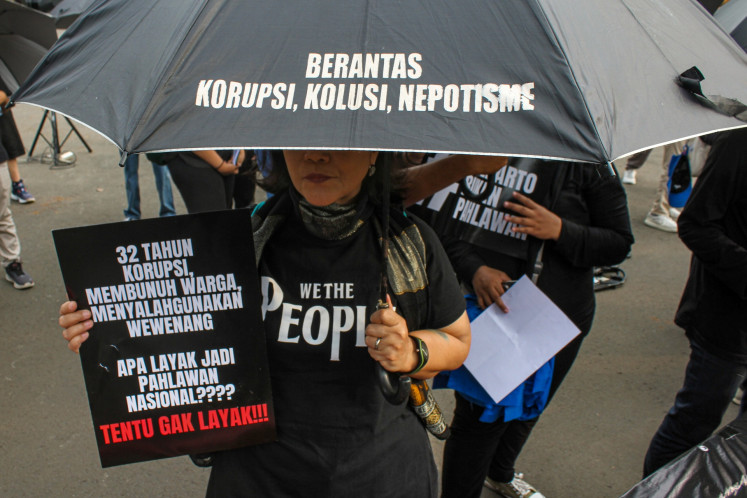

However, following the decree, in early 2016 around 15,000 Gafatar members in Kalimantan faced persecution and forced evictions from their agricultural settlements.

“People raided our community, burned our houses down and took over our properties,” Adam said.

No one was ever legally processed regarding the persecution and looting in Kalimantan.

Adam said the military facilitated the forced evictions, sending the members back to Java on military ships and airplanes “despite the fact that we had been officially registered as Kalimantan residents when we first moved there,” Adam said.

These displaced people are now facing stigmatization from their neighbors in Java.

An effort to move them to places such as Morotai, Maluku, that are open to the transmigration program to develop its natural resources also faced resistance.

“Morotai society wants to keep its region peaceful without deviant ideologies,” a Morotai public figure, Muhammad Salim, said as reported by Antara.

Three of Gafatar’s founders, Ahmad Musadeq, his son Andri Cahya and Mahful Muis Tumanurung were sent to court for blasphemy and treason “because we used the word ‘negeri’ [state] to name the organization. They thought we were a separatist movement,” Adam said.

Mahful Muis Tumanurung and Ahmad Musadeq were sentenced to 5 years in prison, while Andry Cahya was sentenced to three years in prison under the Blasphemy Law. They were found not guilty of treason.

Asfinawati, director of Indonesian Legal Aid, said the government failed to be impartial in this case.

“If Gafatar were criminalized based on MUI’s decree saying that they are blasphemous, why are the people who expressed hatred and discrimination against Gafatar not sent to court too?” she said.

“Intolerant acts also violate the same MUI decree.”

She added that this case adds to the long list of religious based persecution in Indonesia, such as the Tanjung Priok massacre in North Jakarta in 1984 and the Talangsari massacre in Lampung in 1989.

“The government washed their hands of these bloody incidents,” she said.

Bonar Tigor Naipospos, deputy leader of human rights group Setara Institute, said in such conflicts, the government will oppress the minority to prevent large scale unrest.

“It is easier to disband a small organization rather than control an angry majority,” he said. (gis)