Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsHow inclusive is financial inclusion in Indonesia?

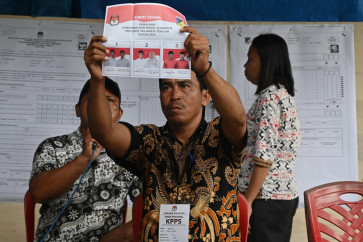

JP/Dhoni SetiawanThe clamor of fintech lending in recent years should not distract us from the various government outreach financial inclusion programs that help more Indonesians gain access to not just loans but also saving, insurance and payment services

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

JP/Dhoni Setiawan

The clamor of fintech lending in recent years should not distract us from the various government outreach financial inclusion programs that help more Indonesians gain access to not just loans but also saving, insurance and payment services. Laku Pandai (Smart Act branchless banking), digital financial services and the digitization of social assistance have contributed to the increase of Indonesia’s financial inclusion rate from 20 percent in 2011 to 36 percent in 2014, and further to 49 percent in 2017 (World Bank, 2018). Nevertheless, at roughly 5 percent of annual growth on average, the inclusion rate for 2019 is estimated at 65 percent at best, thus missing the government target of a 75 percent inclusion rate.

So, what improvements can be made to the running programs to accelerate Indonesia’s financial inclusion? Furthermore, if we compare Indonesia’s progress to that of India or Kenya, the difference is striking. Is there anything that the Indonesian government and authorities have missed so far in their efforts to provide financial services for the unbanked?

There are two categories of a global practice for financial inclusion: (1) bank-led financial inclusion and (2) telecommunications company (telcom)-led financial inclusion. Bank-led financial inclusion is mainly about using banks rather than telecoms to appoint (informal and formal) business entities as bank agents to provide financial services to the unbanked. Indonesia’s financial inclusion is bank-led, since the primary program is the agency bank (Laku Pandai) and Bank Indonesia Regulation (PBI) No. 20/6/2018 prohibits mobile network operators (MNOs) to appoint informal business entities as their e-wallets agents.

Kenya with M-PESA and M-Shwari is an outstanding example of a country with telcom-led financial inclusion. For India, although the Reserve Bank of India’s (RBI) stance has always been geared toward bank-led financial inclusion, MNOs are allowed to use their (informal) mobile money agents to deliver their financial services.

Most Indonesians over 15 years old have access to mobile phones with more than 50 percent of them having a smartphone or tablet. Mobile phone users must have access to MNOs’ (informal) airtime agents, which are ubiquitous even in the remote areas of the country, where a substantial share of the unbanked live. On the other hand, bank agents through Laku Pandai may be limited to where the bank branch exists. Also, as the unbanked are mostly low-income households with frequent and small value transactions, banks are not economically efficient when providing this typical financial transaction.

Thus, telecoms have an advantage over banks for the profitability and sustainability of agents. Nevertheless, in Indonesia, MNOs’ financial product is dedicated only to e-wallets with most people using it as a means of payment or transfer. Of course, people may use e-wallets as a saving account if they register their account, yet the number of registered e-wallet holders is minuscule — in 2018, there were less than 1.1 percent of them.

E-wallet usage that is limited to only payments is related to the fundamental drawback of using MNOs as the leading player of financial inclusion. MNOs are not financial institutions (i.e. run financial services that are not their core business). Thus, for the sake of consumers, the central bank, Bank Indonesia (BI), may have a valid reason to prohibit MNOs from using an informal business entity as their agent.

In India, however, rather than permitting collaboration between banks and telecoms, the RBI permits the telecommunications company to operate as a payment bank: a bank with a small-scale operation, with no lending activities, and limited value of financial transaction and savings. The payment bank is by no means similar to the telecommunication company’s (registered) e-wallet in Indonesia, yet without permission to appoint informal business entities as their agent.

The RBI may be very well confident with the prudency of the payment banks related to the existence of India’s national digital identity system, the so-called Aadhaar. The Know Your Customer (KYC) is not a problem since business entities on a customer-voluntary basis could access Aadhaar for only limited information of the person such as date of birth and gender.

Nigeria also embraces bank-led financial inclusion and has been experiencing a decline rather than an increase in the financial inclusion rate from 2014 to 2017. Nigeria decided to follow in the footsteps of India, as it will give a license to telecoms to operate as a payment bank later this year.

For Indonesia, such a move is doubtful. BI and the Financial Services Authority (OJK) may have put more significant weight on consumer protection and micro-macro-prudential as these are their primary objectives rather than financial inclusion. In line with the risk aversion of the authorities is the not-yet-established integration system between Indonesia’s national identity data and the KYC.

This condition, as mentioned earlier, may lead Indonesia to follow Kenya’s financial inclusion program by pushing collaboration between the MNOs and the banks.

The much similar M-PESA in Indonesia is LinkAja. It is indeed a result of a collaboration among state-owned enterprises, including telecommunications operator Telkomsel and state-owned banks. The partnership to pursue an M-Shwari-like product by LinkAja may very well depend on the structure of profit-sharing among entities and between telecommunications with and within banks.

It is important to note that Telkomsel may use its consumer due diligence as the database for the KYC system and further for credit scoring. For access coverage, it is a must that LinkAja appoints the informal business entity, especially Telkomsel airtime agents, as its mobile money agents. Such could be approved following an agreement between MNOs and banks to create an M-Shwari-like product for LinkAja. Another challenge for LinkAja advancement is on how to designate Telkomsel agents as inclusive agents. In the meantime, each of the banks could have their agents dedicated exclusively for their Laku Pandai services.

Lastly, I would like to remind that, so far, we have mainly discussed the supply side of financial inclusion. However, the backbone of financial inclusion ranges from ICT infrastructure to the financial literacy of the people. Therefore, as the supply side gains progress, the backbone needs to be taken care of. I hope soon it is not just the financial access that improves but also financial resiliency of the poor.

____________________

Head of Research Group for Digital Economy and Behavioral Economics at the Institute for Economic and Social Research — School of Economics and Business, University of Indonesia in Depok, West Java.