Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsDesacralizing anticorruption agency does not defang KPK

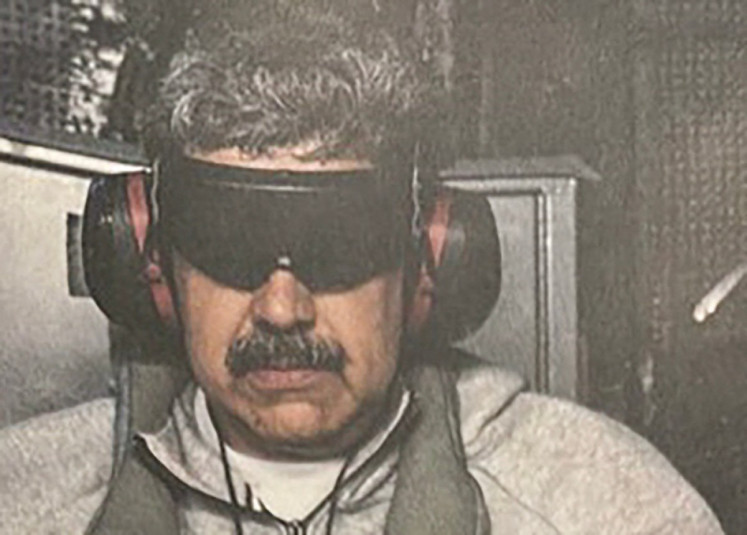

JP/Seto WardhanaIn the debate on the revised Corruption Eradication Commission (KPK) Law, which came into force on Thursday, we should look at the bigger picture through the lens of appropriate organizational principles

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

JP/Seto Wardhana

In the debate on the revised Corruption Eradication Commission (KPK) Law, which came into force on Thursday, we should look at the bigger picture through the lens of appropriate organizational principles.

As the state’s antigraft body that has made numerous breakthroughs, the KPK should operate under proper principles, including having control and supervision over its duties, functions, authority and performance. Implementing these principles does not necessarily intend to defang or even end the KPK but is an effort to prevent the sacralization of an institution. In other words, an institution with such centralized authority has the potential to abuse its power.

Revision of the law has been fueled by the belief that the revision would weaken its independence in implementing its tasks and functions. This belief drove the widespread recent demonstrations, which nevertheless ended in the passing of the new law in September, while deliberation of other controversial bills was delayed.

Advocates of the revision have expressed support for the changes in the KPK’s roles and powers to impede the commission from becoming an extraordinary state body. This revision actually attempts to normalize the KPK’s status in the constitutional law system. So if the KPK is granted the same legal status as other law enforcement agencies, would the revised law really threaten its roles, functions and independence?

There are three fundamental issues concerning the revised law from the perspective of constitutional law studies. First, the KPK’s independence under the executive power. Second, the controlling mechanism over its wiretapping authority. Third, the establishment of a supervisory council.

The questions raised include whether a supervisory council could effectively mitigate power abuse within the KPK. Further, would the controlling mechanism on the wiretapping authority prevent power abuse or contrastingly, will the mechanism actually hinder the KPK’s work in corruption eradication?

Control and power balancing are fundamental premises in the concept of the rule of law. State institutions should also be subject to scrutiny, because of the high possibility of power abuse, particularly as the KPK possesses such great powers, and scrutiny is in line with the good state governance principles.

Another consideration lies in a 1998 decree of the People’s Consultative Assembly; it contains a lesson for everyone on how centralizing power, authority and responsibilities of a state body risks absence of control, which can eventually impact its functionality. Preventing power abuse was a central factor in the democratic movement post-1998 to establish an effective controlling mechanism over the state institutions, especially for those with centralized power.

The KPK is considered an independent state body with centralized power, having authority to initial investigation, investigation, prosecution and even wiretapping.

Consequently, checks and balances should be formed to counter the potential of power misuse.

In addition, the revision of the KPK Law should be regarded as a stepping stone to reconstruct state power amid attempts to consolidate democracy. This is done by placing the KPK as a part of the executive branch, while still allowing it to retain its status as an independent body. With the KPK becoming a government body, it is hoped the KPK would be able to translate the legal vision of the president in preventing and eradicating corruption. The provision of six main duties attached to the supervisory council according to the revised law can also be seen as an instrument to control the use of such great powers.

One highlight of the debate is that the supervisory council would ultimately weaken the KPK; and that the KPK’s new status as an executive body would potentially be compromised by the president’s intervention. This discussion should instead be turned into preparations for a request for a judicial review of the new law at the Constitutional Court.

In conclusion, this KPK law revision only clarifies the status of the KPK, which should clear up the past controversy. On the other hand, however, the legislature’s failure to accommodate President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo’s recommendations of an internal supervisory body has led to more problems, as the new law places the supervisory function outside the KPK’s structure.

The court’s decision on the revised law would be able to restart this process to ensure the continuity of corruption prevention and eradication.

Another option to overcome shortcomings of the KPK is to pass a law on wiretapping, to guarantee proportional wiretapping practices, in which the KPK is one of the authorized parties.

Ultimately, wiretapping is akin to the brahmastra, the ultimate weapon of Lord Brahma in local legend, ensuring the effectiveness of law enforcers’ fight against corruption.

_____________________

Researcher for the politics and social change department, Centre for Strategic and International Studies Jakarta (CSIS Jakarta)