Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsProtecting Indonesian fishermen

In the complicated maritime boundaries between Indonesia and Australia, educating fishermen residing around the border areas is now more pressing than ever.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

M

any in the country seem unaware that Australian authorities burned three Indonesian fishing boats on Nov. 8, somewhere close to the Rowley Shoals Marine (RSM) Park off the Western Australian coast, for alleged poaching. But it was not the first case of incursion into Australian territory by Indonesian fishermen.

However, let us observe at least five points before judging whether or not Australia’s recent action was acceptable. First, we need to understand the status of maritime boundaries between the two neighbors.

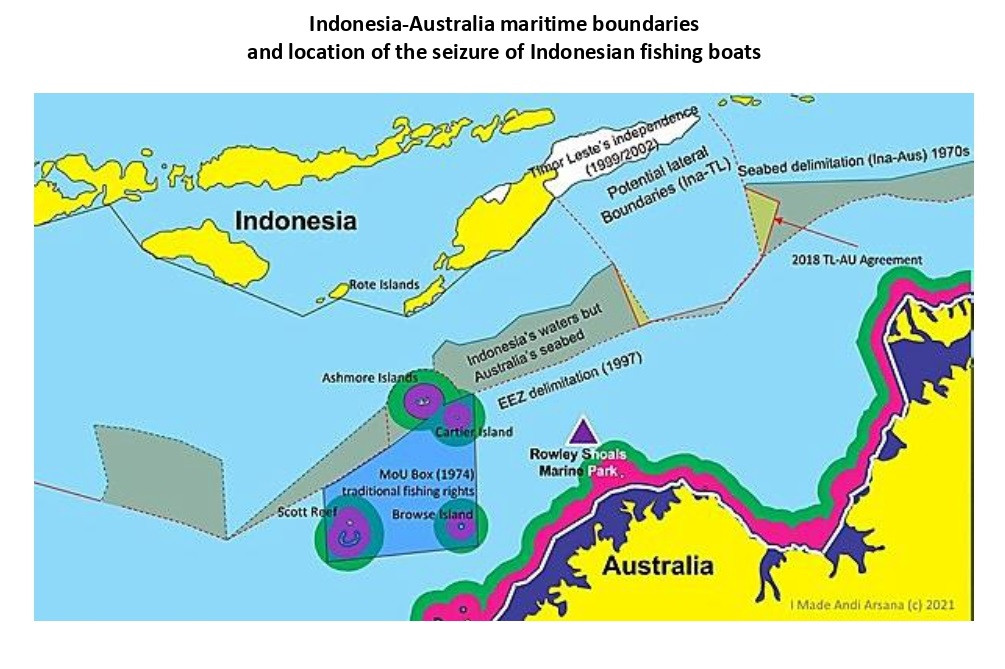

It is clear that Indonesia and Australia have established maritime boundaries between them. The border of the seabed, or the continental shelf, was established in the 1970s, while the water column -- for the exclusive economic zones (EEZs) -- was divided in 1997. With these established borders, it is easy to determine whether or not a fishing boat operates legally.

Second, the position matters. The question is whether the Indonesian fishing boats were operating in Indonesian waters or those of Australia. Unfortunately, information regarding the precise coordinates of the place where the boats were intercepted is not available.

Australia claimed the incident took place near the RSM Park. According to the coordinates on the official website of Western Australia’s RSM Park and a check on Google Maps, the position of the boats was clearly south of the EEZ boundary line between Indonesia and Australia, which means the incident took place in Australian waters.

Third, it is worth noting that maritime boundaries between Indonesia and Australia are complex, typified by differences between lines dividing the seabed and water column. Because of this, there is maritime space where the seabed falls within Australia’s jurisdiction but the water column above it is part of Indonesia. In other words, resources of the water column, including fish, are for Indonesia to harvest but oil and gas under the seabed for Australia.

Another point to note here, is that sedentary species like sea cucumber belong to the seabed. Sedentary species, according to the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) Article 77 (4), are “organisms which, at the harvestable stage, either are immobile on or under the seabed or are unable to move except in constant physical contact with the seabed or subsoil.”