Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

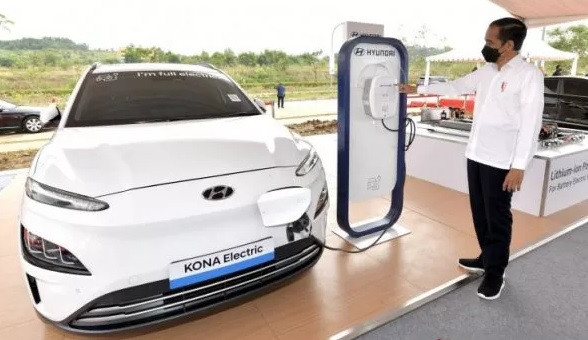

View all search resultsMake Indonesia’s EV metals truly green

The obvious market response has been to seek emissions reductions through plant efficiencies, buying carbon offsets or sourcing from smelters powered by renewables.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

T

he soul of electric vehicles is their promise of sustainability. The EV industry’s kryptonite, however, is not its carbon footprint, but rather it is the unnecessary loss of high-grade biodiversity associated with sourcing minerals for battery production.

Indonesia is leading the global race to supply nickel for electric car batteries. Net-zero policies and aspirations in the rich world have propelled the electric-vehicle transition, turning the attention of companies to securing long-term supply from Indonesia.

Traditionally, most nickel went into stainless steel for consumer goods, but the EV industry is pursuing battery-grade metal in far larger quantities. Previously, these metals have largely been sourced from sulfide ores in Canada, Russia and Australia. As these mines near depletion, Indonesia, with ample laterite reserves on its eastern islands, is in the EV value chain’s spotlight.

The sustainability downside for Indonesia's laterite ores previously was that they require a lot more processing, either through aggressive chemistry (HPAL) or through baking hot furnaces (RKEF) to become battery-grade nickel. As old, new and planned facilities transform deep orange ore into nickel- and cobalt-rich product, the ESG (environmental, social and governance) agenda remains stuck on the higher-than-normal intensity of carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions.

To process Indonesian ore takes a lot more energy and creates a lot more emissions than existing first-generation smelters and those in the pipeline. Processing sulfide ores typically generates around 10 tons of CO2 per ton of nickel. Processing Indonesian laterite ores with HPAL technology, using acids to leach out vital metals, sharply raises the carbon profile. CO2 emissions jump to approximately 60 tons of CO2 per ton when nickel pig iron, produced from blast furnaces, is put through another round of heat to make battery-grade product.

The obvious market response has been to seek emissions reductions through plant efficiencies, buying carbon offsets or sourcing from smelters powered by renewables. Indonesia’s nickel producers report success on meeting emission targets which now compete for attention in annual reports. So clean nickel is a problem that has been solved, right? Well, not quite.

Indonesia’s laterite mines are very often in areas with high forest and marine biodiversity. While relatively small areas are actually mined and restored, the vast majority of unmined areas of forest remain vulnerable to deforestation -- often by poor farming communities. This unnecessary loss of natural capital and the potential for land conflict could exert a drag on nickel sourced from emerging markets like Indonesia.