Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

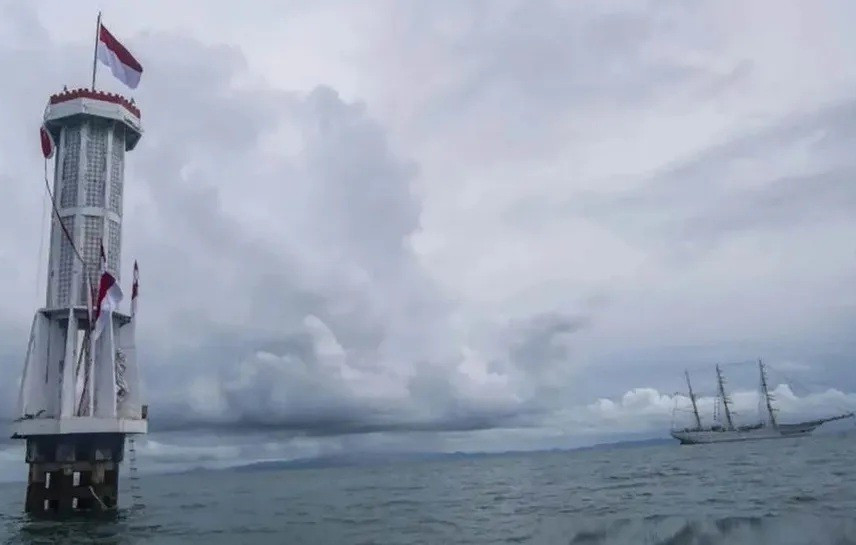

View all search resultsMaritime diplomacy and economic cooperation in Ambalat block

Indonesia and Malaysia's agreement to economic cooperation in the disputed maritime area of Ambalat is one way to keep all channels open, though it cannot replace maritime diplomacy in resolving the decades-long issue.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

T

he unresolved dispute over the border between Indonesia and Malaysia in the Ambalat area has resurfaced after Kuala Lumpur announced that it no longer recognized Indonesia’s long-standing name “Ambalat Sea”, and instead referred to the 15,235-square-kilometer maritime region between Malaysia’s Sabah state and Nunukan regency in North Kalimantan as the “Sulawesi Sea”.

According to Foreign Affairs Minister Mohamad Hasan, the name “Sulawesi Sea” better reflects Malaysia’s legal position and sovereignty.

The issue first emerged when Malaysia unilaterally claimed the mineral-rich waters as part of its sovereign territory on a map issued in 1979. Indonesia, along with several other Southeast Asian countries, protested the new map.

Malaysia’s claim is based on an 1891 agreement demarcating the territorial boundaries between the British and Dutch colonial administrations in Malaysia and Indonesia, respectively. That agreement only addressed land boundaries, however, not maritime boundaries.

Furthermore, Indonesia and Malaysia had agreed in 1969 on the delimitation of their continental shelves. The Ambalat area was already recognized in that ratified agreement as belonging to Indonesia.

Yet a decade later, Malaysia reneged on the agreement by publishing a new map that included the Ambalat block within its territorial waters. Its claim intensified after the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in The Hague ruled in 2002 that the disputed islands of Sipadan and Ligitan belonged to Malaysia.

Emboldened by the ICJ ruling and its 1979 map, Malaysia used Sipadan and Ligitan as base points to claim the Ambalat block, which was inconsistent with the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), ratified by both Indonesia and Malaysia. Under UNCLOS, small islands cannot serve as base points for delimiting a continental shelf. Moreover, Malaysia is a coastal state, not an archipelagic state like Indonesia, and therefore cannot draw its continental shelf boundaries from its outermost islands.