Moralizer or pragmatist? Australia and human rights in Asia

In Asia, Australia has a self-interest in well-governed countries that contribute to security and growth in the region.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

T

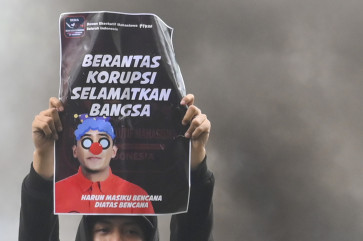

here are two negative stereotypes about Australia and human rights in Asia. One is that Australia is a moralizing Western country that lectures others on human rights despite its own shameful record. This view can definitely be found in Indonesia. The other is that Australia is an amoral pragmatist that stays quiet to cozy up to abusive governments. This can be found among human rights advocates.

Neither stereotype is completely true but neither is completely false. To make sense of this, we need to understand why, when and how Australia promotes human rights in Asia.

Contrary to the stereotype of being uncaring, human rights is an explicit part of Australia’s foreign policy. Australia is an original signatory to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and party to the seven core human rights treaties. It advocates for their consistent and comprehensive implementation and contributes to the multilateral human rights system, most recently through serving on the Human Rights Council.

Australia’s Foreign Minister Marise Payne explains this in terms of Australia’s own self-interest. Respect for human rights underpins global peace and prosperity and a stable international system. In Asia, Australia has a self-interest in well-governed countries that contribute to security and growth in the region.

That the minister is a true believer in human rights is evident throughout her career, but the national interests she describes are long-standing. Australia genuinely believes that the world is a better place if human rights are widely respected.

However, promoting human rights is not Australia’s only foreign policy aim. Australia has three core interests: in its security, its prosperity and in global cooperation. In pursuing its foreign policy, Australia has to balance these.

When dealing with a country where Australia has few other interests, it can decide to advocate strongly on human rights without fearing repercussions. This was the case with Myanmar prior to the (currently stalled) democratization process. With almost no trade and minimal security implications,

it cost little for Australia to denounce a pariah regime for its demonstrable failings.

By contrast, with a country like Indonesia, Australia has massive interests in security and stability that outweigh most other considerations. My colleague Dr Ken Setiawan has outlined how, over decades, human rights have been on the periphery of Australia-Indonesia relations. The Australian government remained quiet on human rights issues due to national security and geopolitical considerations, such as fears of communism or instability.

The reality of Australia’s different interests means that there will inevitably be some selectivity in its promotion of human rights, where it is tougher on some countries than others. It is lower cost for Australia to take a strong position on human rights in North Korea than in India. This means that Australia will sometimes fit the stereotype of a moralizer that lectures others, and at other times may decide to stay quiet due to other interests.

Australia may also sometimes seem to stay quiet when it is working behind the scenes. Australia runs programs aimed at improving human rights compliance, including judicial training, prison training and study tours. The calculation is that by engaging rather than simply condemning, Australia is more likely to get better results. In some cases this has led to significant new human rights infrastructure, such as Australia’s work with the Asia Pacific Forum on National Human Rights Institutions which led to the formation of Myanmar’s Human Rights Committee.

In recent years, Australia has also engaged in dialogue based on peer support. An example is the Australia-Vietnam Human Rights Dialogue where both countries talk about the challenges they face in implementing human rights and what they are trying to do about it. In the last dialogue,

Australia talked about its royal commissions into aged care, treatment of people with disabilities and child sexual abuse. Vietnam talked about its adoption of new legislation related to human rights and its plans to revise its Labor Code to comply with international conventions. Critics will say that the dialogue did not talk about the countries’ most egregious abuses, which is true. What’s interesting is the degree of openness to share what each government is grappling with and seek support.

Conceptualizing human rights promotion as including peer support potentially offers a way to break down both stereotypes about Australia. It shows that Australia is not a hypocritical moralizer; it engages in a two-way mutual process and accepts its own fallibility. It shows that Australia does not callously disregard human rights; it supports others to strive to meet their obligations.

Peer support could never be the only technique used to promote human rights. There will always be a need for declaratory denunciations and the imposition of sanctions, for example in cases of large-scale abuses where it is important to bear witness and to affirm universal support for human rights. But it is one way countries can try to encourage each other.

International human rights protection is only a very recent invention. For almost all of human history, most people were subject to arbitrary power. It was an enormous advance to agree on a set of human rights as a touchstone for judging states’ behavior. This does not mean that human rights are always respected: the norm is still that they are not. What we have achieved is a common aim, even if there may be differences in interpretation.

Understanding human rights as a shared aspiration—one that all countries are failing fully to achieve but should continue to strive for—can help create a sense of common endeavor.

***

Asia Institute research fellow; this article has been copublished with Melbourne Asia Review, Asia Institute, University of Melbourne.