Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsFrom student brawls to ‘klitih’: On the origin of teen gang violence

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

T

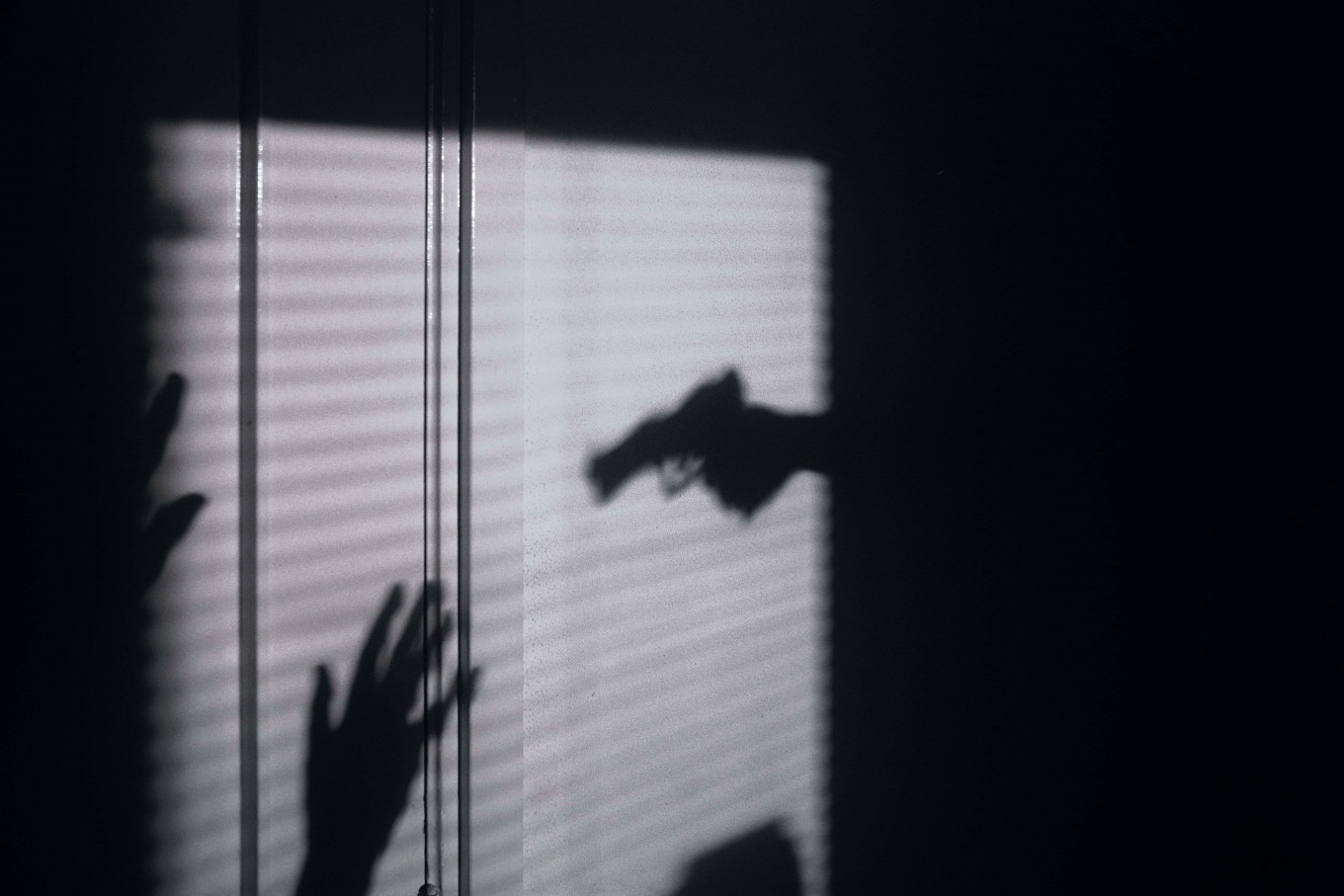

eenage gang violence is seeing a deadly rise recently in Yogyakarta’s ‘klitih’, to the surprise of even its ex-perpetrators. But what drove such acts from teenagers?

It was a breezy afternoon when Pacul (not his real name), a history teacher at a state high school in Yogyakarta, sat down for a talk with The Jakarta Post on April 15. He had no class to teach that day, but Pacul remained restless during the holiday.

“Klitih still goes on, regardless. Even when we had online classes, a lot of klitih still happened,” he said.

The reason he knew the teenage gang activity so well? Pacul was a former klitih perpetrator himself. And the school that introduced him to the scene was the same one he currently teaches at.

“One of the reasons I became a teacher, especially at my old high school, is to fix my ways,” the 26-year-old said. “As an older, wiser person who can think more clearly, I want to be an example for them.”

But in the last couple of years, the klitih cases looked more and more horrendous, even for Pacul. Last year alone saw almost 60 cases of the teen gang violence act in Yogyakarta, according to the local police, with several of them ending in death.

The drive

Klitih, traditionally, was a Javanese term for going out for some fresh air at night. That definition was long gone when teenage gangs claimed it for their downtime violent attacks on other students. But its recent sporadic attacks on random people baffled its past players because until some years ago, there were still some “ethical codes” that they needed to uphold.

“Back then, targeting women was very much forbidden. Or when she’s with her partner on a motorcycle, that’s also forbidden. It’s also not allowed to attack schools that you don’t have beef with,” Pacul explained.

But Pacul still saw the same old pattern in newer cases. ”As long as the case involved two motorcycles attacking one person, that’s still klitih. If it’s ten bikes against ten, that’s just straight brawl,” he added. “And these days, klitih perpetrator is rarely a student — just a nearby villager.”

Many student gang members often unite with villagers from their area as well — at least that was the case for Hadi, now an IT staff at a private university in Jakarta.

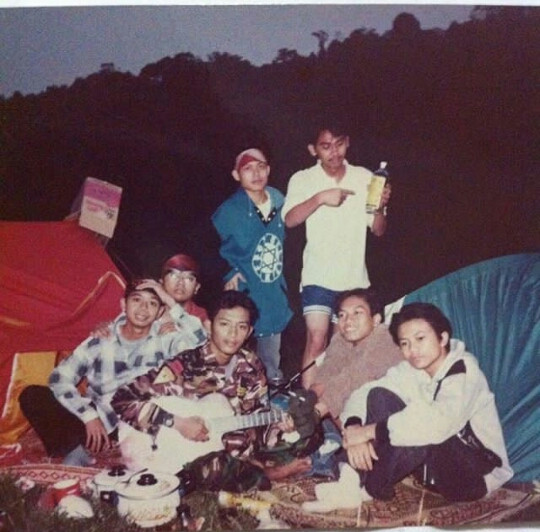

“Our reason for brawling was always a territorial thing,” he told the Post on April 12. Hadi and his gangmates, being from Bogor, usually targeted kids who “trespassed” their territory in the 1990s. “If there’s a Jakarta student going on our train, man, he’s done for,” he said.

Together forever: Hadi (blue shirt) is pictured with his close-knit schoolmates during a trip in 1996. (Courtesy of Hadi) (Personal Collection/Courtesy of Hadi)Gang brawls' motivation shifted a decade later for Bintaro-based graphic designer BRQ, going by his gang initials. “We usually go for man-to-man fights, so it’s like boxing,” BRQ said to the Post. It was even treated as an (illegal) sports club at his high school in South Jakarta in 2009, taking place every Friday.

But in whatever form the gang activity took place, and despite its fatalities, all of them agreed that the brawls were done in the name of pride.

“I didn't do it for the sake of hurting others, it’s just merely for honor and popularity,” BRQ said.

And surprisingly, Pacul even saw the positive in klitih. “It trained me mentally and taught me leadership values,” he said. “I don’t regret a thing because I was still a responsible student in the end. Although, yeah, the ‘hurting others’ part is negative…,” his words trailed off.

Students after all: Pacul (left, white-pink shirt), a name he prefers to be called, stands together with his schoolmates for a picture in 2011. (Courtesy of Pacul) (Personal Collection/Courtesy of Pacul)Never-ending cycle

Most students in an unfortunate environment have never had a chance to get out of the gang circle.

“We alone got into gang brawls because of the pressure from our alumni,” RAM, going by his initials, confessed to the Post. He is a fresh graduate of a vocational high school (STM). “If we weren’t brave enough [to go brawling], we really can’t go to school,” he said.

BRQ painted the scene more vividly. “You’re a new kid in school, looking for friends. When you hang out, the seniors will act tough, abuse you during orientation and push you to brawl. If you lose, they’ll either step up or constantly kick you so that you can’t back down. That’s the cycle,” he said. “These freshmen will then be the seniors and use the same violence during orientation.”

This was what Pacul experienced and eventually did to his school’s freshmen in 2013. The repetition also happens whenever someone gets killed in a brawling.

“That’s when the cycle shifted into endless revenge. An eye for an eye,” BRQ said.

Before the action: BRQ (right, green shirt), going by his gang initials, sits tight with his gangmates on the side of the street in late 2009. (Courtesy of BRQ) (Personal Collection/Courtesy of BRQ)Socioeconomic factors

From schools’ lack of attention to children’s access to a motorcycle at an early age, the blame has been put on one too many things.

“From a psychological perspective, there’s a lot of factors to [teen gang violence]. But one of them is the culture of violence that surrounds the teenagers, meaning that since they were little, they have been exposed to and are familiar with it,” said professor of psychology and social work at Bhayangkara University Dr. Adi Fahrudin to the Post on April 14.

This exposure to violence, he said, usually comes from the overcrowded, densely populated, and slum-like area in which they live. Studies have shown that children from such areas tend to be involved in delinquency and crime due to the tough economic competition and education access.

"These incidents of youth violence always happen in the same area. The fights are also unique, first between villages, between districts, then it leads to gangs,” Adi said. “In some cases, it involves adults as well, [which shows] that this culture of violence in the overcrowding environment was passed down, shaping them,” he explained.

Pure economic reasons also motivate a lot of teen gang members, especially non-students. Hadi said that the kids he met next to the Depok train station got into brawls and robbery to make a living. “They said 'If I didn’t do this, I wouldn't make any money,’” he shared.

But the problem becomes more complex due to another factor: the youth’s attempt in finding their identity.

“If you didn’t get into the gang, you won’t have friends. You’ll just be friends with the losers at school,” BRQ confessed at one point in the interview.

To fight this reasoning, the concept of self must be introduced by parents early on. “So early education within the family about norms, values of friendship and healthy competition are very important," Adi said.

But even if a family does little in this nurturing phase, a good social environment can help the kid grow, which is why Yogyakarta-based artist Yahya Dwi Kurniawan felt glad he moved out of Magelang.

“Even after I graduated from high school, I used to still do klitih,” he said to the Post on April 13. But after moving to Yogyakarta, he met new people and fell in love with the world of arts. “From that point, there’s no conversation about violence anymore, only ‘Artworks! Become an artist! Drawing!’ I got a new perspective,” he shared.

Yahya presented an art exhibition about klitih in 2021, educating the masses and inviting klitih perpetrators themselves to write, draw and make arts together.

“At least they found a new reference in life, like, ‘Oh, so I could do some drawing or do this kind of exhibition,’” he explained, hoping he could help break that vicious cycle of violence.