Lessons learned from the 1997 Asian financial crisis

The disappearance of the “iron curtain” or the harsh borders between socialist and capitalist economies raises the number participants in and the of fierceness of global competition.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

G

rowth is a required element for the improvement of the standard of living, whichever way it is defined. Even for Singapore, Japan and South Korea growth is still needed to allow citizens to enjoy a greater diversity of goods and services as a way of raising an already high standard of living.

This brings us first of all to the short-term challenges of safeguarding economic growth despite the lingering effects of and scars from the COVID-19 pandemic; the inflationary pressures, external shocks and years of easy money and related policy reversal and the exacerbation of pressures following the Russian-Ukraine war.

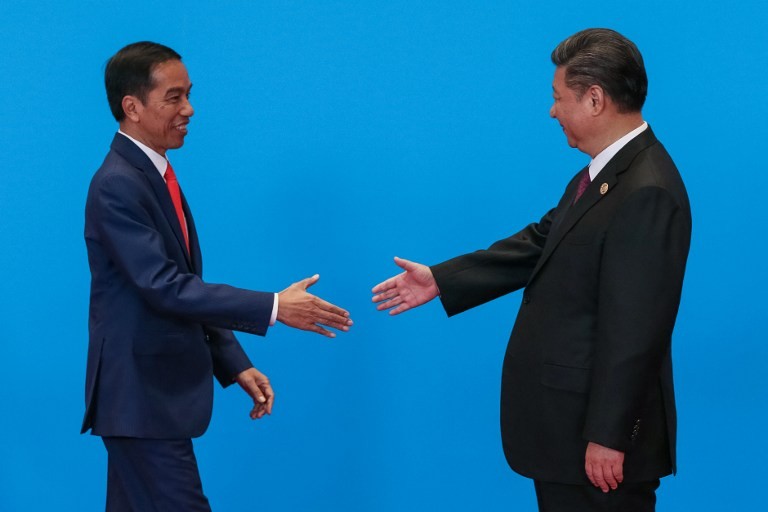

Even though ASEAN, China and the rest of East Asia are projected to suffer a milder downward correction of growth this year and in 2023 than the developed economies of Europe and North America, an East Asian concerted policy of recovery is needed. Countries in which inflationary pressures are softer and government resource positions are more favorable should agree to do more in terms of stimulating aggregate demand. Secondly, recognizing that ASEAN and China have a long way to go before they arrive at an advanced stage of development with adequate resilience to possible retrogression or Sisyphean development cooperation is indispensable to generate and continuously renew sources of growth.

Consistent implementation of the myriad agreements on strategic partnerships with the focus on market sharing, such as the agreement on the three ASEAN communities, the ASEAN+1 agreements, the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) and the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) can open new growth opportunities of both a static and dynamic nature.

We have spent years negotiating these agreements and we should care even more about their consistent implementation. Yet, we need to go beyond existing agreements in order to maximize our probability of success in the emerging, technologically new world.

Openness alone is insufficient to craft durable international competitiveness. The diversification of products and services that a country can offer to the rest of the world requires at least a little push from governments. To an important degree, the story of East Asian successes is one of market-conforming industrial policies.

When it finally saw the imperative of concrete economic cooperation, ASEAN also agreed on a coordinated industrial policy in the form of the ASEAN Industrial Projects (AIPs). While the AIPs largely failed to deliver, the core idea was pursued further in the 1980s through the ASEAN Industrial Joint Ventures (AIJVs) and ASEAN Brand-to-Brand Complementation, but this private sector industrial cooperation also largely failed to deliver.

We were not determined enough to walk the talk. Obviously, member economies were doing well with shallow intra-ASEAN economic cooperation, particularly thanks to expanding trade with the fast-growing economies of East Asia and the preferential access to Australia and New Zealand (ANZ), West Europe and North America provided in those years under the Generalized System of Tariff Preferences (GSP).

Those privileges are now gone. Global competition has been redefined with the rise of complex technology propelled by digitalization that has helped transmit progress in one field to another much more easily than was the case prior to digitalization. At the same time, the disappearance of the “iron curtain” or the harsh borders between socialist and capitalist economies has raised the number participants in and the fierceness of global competition.

Two of the most successful of these metamorphosed economies are our partners: China and Vietnam. The rise of digital technologies and the migration of socialist economies to capitalism combine to result in a truly global economy starred by truly global companies. A competitive edge, usually rooted in technological innovation, can now be upscaled in the blink of an eye to the entire world as we experience every day with digital machinery and equipment.

It is time for ASEAN to wake up and reinvent its economic cooperation. Needless to say, it should do so together with its strategic partners in East Asia, including, and probably in particular, China. The best way of celebrating our successes of weathering the financial crisis of 1997, insulating ourselves against and getting out of the global financial crisis (GFC) of 2008 better than West Europe and North America and recovering stronger from the severe impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic is to lay the platform for reinvented regional cooperation in our part of the world.

In doing so, we reaffirm our commitment to open regionalism. The reinvented design should also serve as a “second best” solution to global governance, in recognition of the deeply entrenched constraints facing global institutions like the World Trade Organization.

In addition to pushing ahead with the implementation of existing agreements, a vast area of novelty is open for cooperation in East Asia. I would like to mention a platform for science and technology cooperation in particular. In technology-intensive East Asia, technological capabilities determine the ability of countries and their people to benefit from cooperation and integration.

The platform should help mobilize collaboratively the science and technology capabilities of the government, university and corporate research and development centers of excellence of the region with the aim of allowing the region to originate, rather than copy, next-generation technologies.

Communities of scientists and policy researchers know better which areas of the immense frontier of progress should be attached top priority. Just to illustrate, I can imagine such a list to include next-generation semiconductors, next-generation computing, next-generation genome editing and next-generation renewable energy.

The platform should also include the social dimensions of cooperation such as: (i) next-generation food security regimes; (ii) an East Asia disaster management fund; (iii) concerted intellectual property protection regimes; (iv) An East-Asia-wide education program, somewhat akin to the European Union’s Erasmus Program to enable institutions in the region to supply scientific and applicable ideas on human progress as well as to ensure that East Asian citizens are equipped with literacy and hard and soft skills that are required to thrive in the science-intensive landscape and (iv) concerted competition policy aimed at minimizing the abuses of market power by global corporations. This illustrative list can easily be extended provided a sense of urgency for deep cooperation is sparked among leaders.

I do see the logic for the centrality of ASEAN to a reinvented open regionalism in East Asia. In that sense, we in ASEAN are challenged to come up with policy ideas commensurate with our privileged status of being central to the evolving East Asian open regionalism.

However, it should not matter much where the policy ideas originate from. Given China’s success in elevating almost one-fifth of the world’s population to the upper-middle-income group in a matter of a little more than one generation, China is equally challenged to generate ideas on reinvented open regionalism in East Asia on top of the major initiatives that it has launched recently such as the Belt and Road Initiative and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank.

Our success in a transformed East Asian open regionalism should be even greater than what we have accomplished in the 25 years after the Asian financial crisis of 1997.

***

The writer is vice chair, Board of Trustees, CSIS Foundation. This is the second of a two-part article.