Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsWhat do fintechs have to do with social justice anyway?

Studies have demonstrated unchanged gender dynamics after two and a half decades of microfinance, with some even pointing to increased domestic violence correlated to women’s access to credit.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

B

esides taking over 150,000 lives, the COVID-19 pandemic has plunged the most vulnerable into deeper destitution. An estimated 2.6 million people have lost their jobs causing unemployment rates to reach a record high within the last decade.

The economic crisis brought upon by the virus is also reflected in the relegation of Indonesia’s classification by the World Bank to a mid-income country from its previous upper-middle income status. Curiously, the share of rich and ultra-rich citizens soared during the pandemic with the number of individuals having a net worth of US$1 million seeing a substantial 62 percent increase, pointing toward an exacerbation of income inequality in the nation.

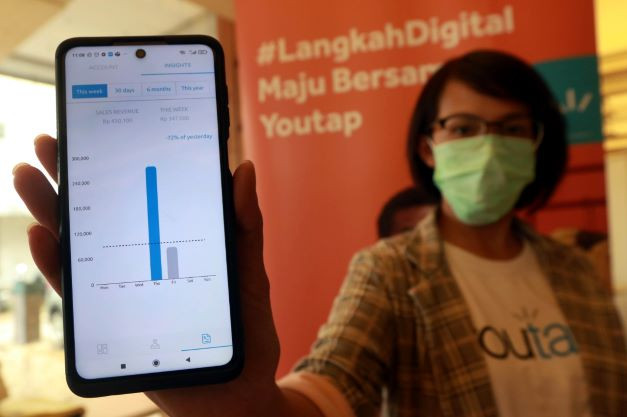

Not coincidentally, large private investments into fintech startups, one of the fastest growing segments in the startup scene, did not wane but rather rushed in. In particular startups targeting micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) have been met with fervor, attracting multimillion investments from the likes of billionaire investors such as Jeff Bezos and Peter Thiel along with some of the biggest international venture capital firms.

Digitalized interventions led by the fintech-philanthropy-development (FPD) complex purports to financially include the poor by offering financial services by selling “a vision that celebrates the possibilities for simultaneously achieving positive returns, philanthropy and human development”.

The timing of such investments makes sense. The financial strain placed on state budgets and citizens has proven to be a strong thesis for powerful investors to push the government to liberalize the financial services market, thereby making it competitive for a variety of financial institutions to enter a coveted space by betting on the economic growth of the burgeoning underclass.

Within such institutions that aim to render financial services more accessible to the poor, the term financial inclusion (FI) is rampantly used. For instance, The World Bank’s definition on its website claims that FI is a key enabler in reducing poverty and boosting prosperity.

When it comes to elucidating what exactly it entails, scholars have noted that FI’s scope is so broad that one would not be wrong to think that financial inclusion is nothing more than a feel-good term that evades specificity in its definition and consequently, opprobrium. After all, who would argue against reducing poverty and boosting prosperity?

Ideologically speaking, FI’s theory of change is that when traditionally excluded people have access to financial services, then they are able to clutch on to the rescue float that delivers them from the proverbial depths of poverty. This theory of change ties in to the ascendance of social enterprises, social ventures, social impact, all of which imagine new possibilities of solving pressing and complex social issues through market-based methods.

However, much like its predecessor, microfinance – once the golden child in development – the evidence that these solutions are bona fide transformative tools in poverty eradication have been mixed at best. To illustrate, microfinance initiatives have regularly provided loans to rural women with the assumption that upward mobility will empower them against routine patriarchal hegemony.

Regrettably, studies have demonstrated unchanged gender dynamics after two and a half decades of microfinance, with some studies even pointing to increased domestic violence correlated to women’s access to credit.

Phillip Mader, a researcher at the Institute of Development Studies, points out similarities in microfinance and FI, both of which are reliant on limited evidence and yet receive widespread endorsement. Desperate times brought upon by the pandemic also saw desperate measures.

The government has found itself playing whack-a-mole with extrajudicial pinjol (short for pinjaman online or online lending, many of them informal and unsupervised) terminating over 3,000 of them since 2018 alone. Much like microfinance, greater access to loans opens the floor for middle-income earners to become self-fashioned middle-men, siphoning capital into a black market and targeting borrowers with great barriers and greater need.

In Indonesia, where microfinance schemes are the most available in the world (along with Bangladesh) this practice is more commonplace than one would expect, entrapping the poor in perennial poverty and perpetuating systemic inequality.

A popular response to the lack of evidence that FI has tangible positive developmental and poverty alleviation effects is that it isn’t FI that does not work – the poor just do not make prudent financial decisions. They do not know how to maximize the use of financial services offered and remain poor because of the lack of attitudes, skills, behaviors and knowledge to make future-proof financial choices.

FI actors require individuals to chart their own trajectory out of poverty, thereby equating one’s inability to break the surface as a personal moral failing. The most compassionate rhetoric often cites the effect of poverty on cognition, how financial distress lowers IQ, or variation of such evidence.

As a solution, actors have argued for “financial literacy” as a core and integral component of FI. However, while over-indebtedness is seen as a marker of the individual borrower’s poor choices, rarely do unfavorable socio-market structures that distribute wealth inequality in the first place ever be evoked in the design and delivery of financial literacy programs.

It is perhaps paramount to go back to the beginning, against the grain of wide support toward FI and ask fundamental questions, as well as critically think of our base assumptions on what we are seeking to alleviate. In a society that takes market-based interventions for granted, it is equally imperative to examine how markets have historically engendered inequality.

Therefore, echoing Mader’s observation, keeping our fingers crossed that FI would solve unemployment, poor skills, income irregularity, poor housing, high crime environments, bad health and family breakdown is analogous to putting the cart before the horse. Despite global poverty alleviation being at the forefront of developmental agendas for decades, we must not eschew the formidable tectonic plates of political and power ideologies that structuralize the distribution of wealth and resources.

Failing to critique these ideologies, we risk suppressing, overlooking and contesting social justice theory and praxis that dream beyond alleviating poverty, but also fostering equitable, dignified and creative lives for everyone.

***

The writer is a senior associate at BukuWarung. The views expressed are his own.