Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsIndonesia can help repair ASEAN’s authoritarian drift

The fake election that took place in Cambodia in 2018 is the blueprint for the plan by Myanmar’s junta to devise a bogus electoral exercise to try to secure a fig leaf of legitimacy.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

I

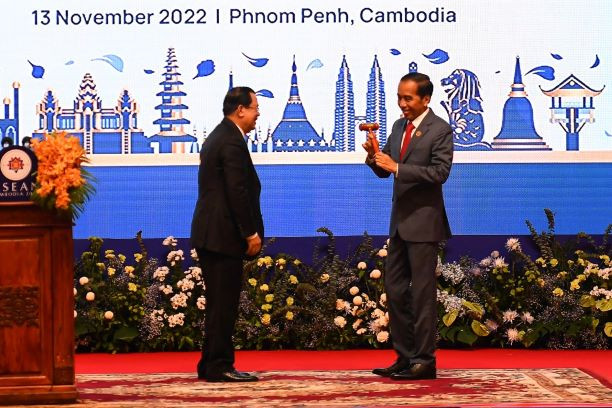

ndonesia’s chairmanship of ASEAN this year offers an opportunity to move beyond the sterile process of running down the clock witnessed under Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen in 2022.

ASEAN failed to achieve anything in regard to the illegitimate military junta in Myanmar last year as Hun Sen simply waited to hand the problem over to someone else. Hun Sen and his representatives failed to meet with National League for Democracy (NLD) leader Aung San Suu Kyi or any representative of the National Unity Government (NUG), which represents the will of the vast majority of Myanmar’s people.

Hun Sen looked on in passive acquiescence as Suu Kyi was sentenced to 33 years in prison, including three years of hard labor. The ASEAN doctrine of noninterference to which Hun Sen enthusiastically subscribes makes such monstrous behavior by Myanmar’s junta possible.

The only contribution made by Hun Sen as chairman of ASEAN that anyone will remember in the future is his gift of luxury watches, for which he has an enduring fondness, at a summit in November. Cambodia, in case you were wondering, does not have any tradition of watchmaking.

The fake election that took place in Cambodia in 2018 is the blueprint for the plan by Myanmar’s junta to devise a bogus electoral exercise to try to secure a fig leaf of legitimacy. In Cambodia, the opposition Cambodia National Rescue Party (CNRP) was dissolved by order of the politically controlled Supreme Court in 2017.

The ruling Cambodian People’s Party (CPP) won every single national assembly seat in the 2018 election, with not a whimper of protest from ASEAN and very little international reaction. Such timidity on the part of the international community encouraged Myanmar’s military in its calculation that it could overthrow a democratically elected government with minimal risk of repercussions.

Myanmar’s military “leader” Min Aung Hlaing has said he plans to hold an election in 2023. He expects to get away with it, just as Hun Sen expects to succeed in another bogus Cambodian election in July.

ASEAN was founded in 1967. Myanmar, Cambodia, Vietnam, Laos and were all late entrants. These countries tilted the balance of power within ASEAN away from Indonesia and Malaysia, which have historically been among the organization’s progressive influences.

Indonesia, as cochair of the 1991 Paris Conference on Cambodia, played a key part in the peace agreements of that year, which laid down a pluralistic system of multiparty democracy. This democratic system is also guaranteed by Cambodia’s constitution, but has long been ignored in practice by Hun Sen. Indonesia has consistently adopted a constructive leadership role within the bloc.

While other ASEAN members adopted a passive approach, Indonesia played a key part in defusing tensions between Cambodia and Thailand over the disputed Preah Vihear temple in 2011. Indonesia and Malaysia both criticized Hun Sen last year for going to Myanmar without consulting other ASEAN members.

Today, Indonesia’s chairmanship can be a catalyst in reestablishing the political will for democracy in Cambodia. The minimum standards for free and fair elections in Cambodia include the safety and security of voters, political parties, independent media and civil society. The CNRP must be reinstated and its leader Kem Sokha, the victim of an endless politically motivated trial on bogus charges, must have his political rights restored. The party must be free to choose whoever it wants as candidates at the election, including me.

Already in 2023, Hun Sen has publicly threatened anyone who criticizes his ruling party with violence. The people of Cambodia know that his words are not empty threats. Political assassination in Cambodia has remained a reality since the 1997 grenade attack on a peaceful protest march in Phnom Penh that killed 16 and wounded at least 150. Two of Hun Sen’s bodyguards are due to face trial before a French court for their role in organizing the attack. The involvement of the French court arises because I was the target of the attack and am a citizen of both France and Cambodia.

The great failing of the ASEAN doctrine of noninterference and of the piecemeal caution that the wider international community has shown in Southeast Asia is that the invisible encouragement given to violent or would-be violent authoritarians is not taken into account. This increases the dangers for all ASEAN citizens of having to live, like the people of Myanmar, by the law of the jungle.

The growing influence of China in ASEAN has made the concept of noninterference redundant. Hun Sen has allowed China to establish a naval base at Ream which violates Cambodia’s constitutional obligation to remain neutral and threatens the stability of the whole region.

Chinese money has also meant that Cambodia has emerged as a regional hub for cyber slavery. As shown in the Al Jazeera documentary Forced to Scam: Cambodia's Cyber Slaves, people across Southeast Asia and beyond are being tricked into coming to Cambodia on the promise of a well-paid job, and then being locked up and brutally forced to carry out scams online. It is estimated that as many as 100,000 have been held captive.

Human rights and security are shared regional concerns rather than the exclusive internal prerogative of member states. As a Group of 20 member, Indonesia is well placed to shape international approaches to Southeast Asian issues. The plan announced by Foreign Minister Retno LP Marsudi to create a special envoy’s office to coordinate ASEAN’s handling of the Myanmar conflict is a positive step that should have been taken last year.

The people of ASEAN thirst for genuine democracy, human rights and the rule of law as enjoyed in the free world. For many, these are aspirations rather than realities. The organization cannot afford a further year of drift. I am convinced that Indonesia can help chart a progressive future for ASEAN.

***

The writer is cofounder and acting president of the Cambodia National Rescue Party (CNRP).