Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsIndonesia may need to ‘tread lightly’ with BRICS interest

Analysts warn of potential to alienate global partners.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

A

s President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo embarks on his Africa tour this week amid a polarized geopolitical landscape, any move by Indonesia toward joining BRICS, the emerging powers bloc, would raise concerns about the nation’s “free and active” foreign policy.

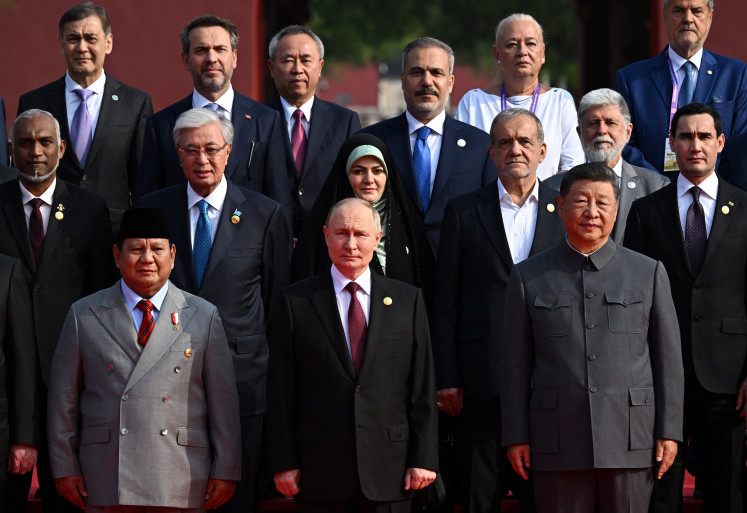

The question of expanding the group consisting of Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa was the topic of recent talks ahead of a summit in Johannesburg on Tuesday, where BRICS leaders were expected to decide on admissions criteria for new member states.

The BRICS pledge to become a champion of the developing “Global South” and offer an alternative to a world order dominated by wealthy Western nations has resonated with many around the world. South Africa even claims that 40 countries have expressed an interest in joining.

BRICS’ current five members account for over 40 percent of the global population and over a quarter of the global economy, surpassing the economic prowess of the Group of Seven industrialized nations.

Indonesian officials have acknowledged the merits of joining BRICS, while observers have also touted Indonesia as a “strong candidate” given its growing role in the global economy.

Yet, the decision to join could weigh heavily on Jakarta’s long-standing policy of nonalignment, at a time when it is often mistakenly regarded as being in league with China.

United States Trade Representative Katherine Tai said on the margins of an ASEAN-led meeting in Central Java that she would be interested in learning more about Jakarta’s motivations but that the US would respect Indonesian sovereignty.

President Jokowi, who is to attend the BRICS Summit at the invitation of group chair South Africa, has made vague remarks about Indonesia’s interest in joining, while the Foreign Ministry has been silent on the matter recently, reportedly due to the geopolitical sensitivity around it.

In a virtual address to the Friends of BRICS ministerial meeting in June, Foreign Minister Retno LP Marsudi bemoaned the breakdown in international cooperation on multilateral platforms to address global challenges, describing it as “unhealthy” and prone to propagating “economic injustice” on developing countries.

“We all have a responsibility to remedy this unhealthy global order. And BRICS has the potential to be a positive force for that,” Retno said at the time.

Meanwhile, officials from elsewhere in government have framed Indonesia’s interest in BRICS around the potential multipliers for Indonesian economic interests, which would otherwise be elusive in groupings such as ASEAN or the Group of 20 largest economies.

Jokowi has suggested that his tour of Africa is meant to “strengthen solidarity among nations of the Global South”.

The President was en route to Mozambique on Tuesday after state visits to Kenya and Tanzania. He is to conclude his trip in South Africa, where he is set to meet with other African leaders on the margins of the 15th BRICS Summit.

Jokowi is to deliver an address on the last day of the summit on Thursday.

Tread lightly

BRICS leaders met on Tuesday under the shadow of heightened global tensions provoked by the Ukraine war and a growing US-China rivalry, which have added urgency to calls to strengthen a bloc that has at times suffered from internal divisions and an incoherent vision.

But to say that BRICS is simply an economic coalition without any potential to alter the makeup of geopolitics would be erroneous, foreign policy analysts have said.

Some even go as far as to warn that Indonesia might not be fully prepared to face the implications of joining BRICS.

“We need to be crystal clear on the essence of BRICS, which is a revisionist grouping with a layered foreign policy designed to change the world’s order,” said Andrew Mantong, an international relations expert from the Centre for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) in Jakarta.

“Policymakers in Jakarta must be sober in considering the normative implication of signaling their interest in joining,” he asserted.

Andrew pointed out that as a middle power with a history of nonalignment, Indonesia has never wished to revise the status quo of global economic institutions like the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Trade Organization (WTO).

Instead, Jakarta has lent its diplomatic clout to the Mexico, Indonesia, South Korea, Turkey and Australia (MIKTA) grouping, a coalition of middle-power countries seeking to reform, not revise, the global order by strengthening its collective diplomatic and bargaining power.

“Indonesia has gained the reputation of being a power in the middle, not a middle power,” the researcher said.

“We cannot be dictated by great powers, but if we do join BRICS [without ample preparation], I fear that we will become norm-takers with a stunted free foreign policy.”

Alluring idea

Other analysts find it hard to deny that joining a group like BRICS would not be an enticing idea for Indonesia, whose domestic agenda is currently facing roadblocks imposed by Western powers and institutions under the status quo.

For instance, Jokowi’s downstream vision for the Indonesian critical minerals industry faces an uphill battle at the WTO, whereas crude palm oil, its top commodity export, faces the possibility of being banned from entering the European Union market over links to deforestation.

But as enticing as it is, CSIS executive director Yose Rizal Damuri said that aligning too closely with a group that serves as a counterpoint to the West, especially with the likes of China and Russia in tow, would make for a dicey undertaking considering current geopolitical tensions.

China, looking to increase its political clout at a time of trade tensions with the US, has long pushed to expand BRICS. Russia, isolated diplomatically over its war in Ukraine, is also embracing the chance to court allies.

Both actors featured heavily in debates that led to an impasse at one time or another during Indonesia’s G20 presidency and this year’s ASEAN chairmanship.

“If Indonesia joined BRICS five years ago, there would not have been any debate about it. But it isn’t the same now. Has Indonesia carefully considered the implications of possibly alienating its [other] economic partners?” he said.