Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPertamina gets Rokan oil block from Chevron. What does this tell us?

Some have claimed that the decision lacked transparency.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

I

ndonesia’s decision that state-owned gas and oil company Pertamina will take over one of the country’s most productive oil blocks from US energy firm Chevron shows a push towards a nationalist agenda ahead of the country’s presidential election in 2019.

But despite this shift towards protectionism, Indonesia under President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo still practises a mixed model economic policy.

The precious Rokan block

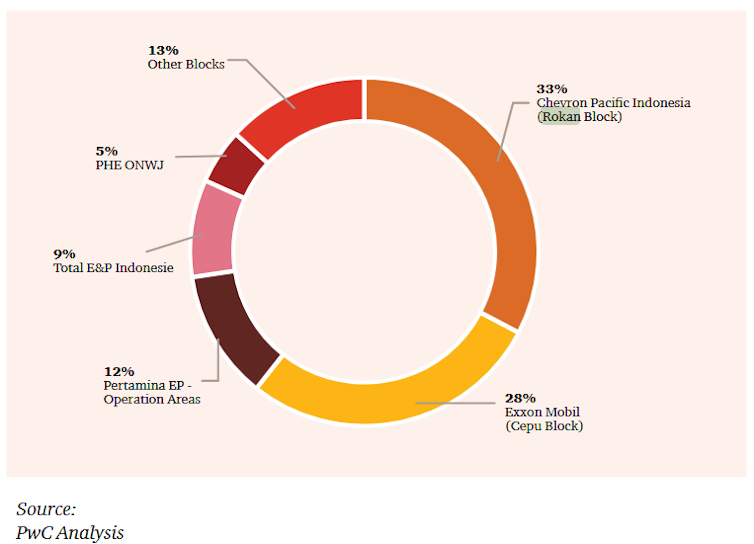

Chevron is a major oil producer in Indonesia and has operated the Rokan block in Riau on the island of Sumatra, one of the country’s most strategic oil blocks, since 1931. Its contract with Indonesia will end in 2021. Under a regulation, Chevron is able to request an extension. However, the government decided to reject the request and gave the block to Pertamina as the state company came up with a better offer.

Pertamina claimed that the deal could help Indonesia save US$4 billion a year in oil import spending and cut downstream costs in the long term. The acquisition will also improve Pertamina’s upstream and downstream businesses.

However, concerns are growing over the Indonesian government’s decision to give the oil block to Pertamina.

Some have claimed that the decision lacked transparency. Global financial services company Moody’s Corporation was pessimistic about the deal. It said the deal would become too much a burden for Pertamina as it required the company to spend $70 billion over 20 years.

The nationalist agenda

The Rokan block deal tells us that the Indonesian government is pushing for an inward-looking economic policy. Such a policy tends to limit foreign direct investment and to impose tariff and non-tariff barriers to support national economic interests.

Previously, the government, via its mining holding company PT Indonesia Asahan Aluminium (Inalum), clinched a deal with US giant miner Freeport-McMoran to buy 51% of Freeport Indonesia’s equity. The deal gives Inalum’s control of the world’s largest gold mine, the Grasberg mine in Papua. However, many have doubted its capacity to manage the mine.

For the Freeport deal, Inalum paid US$3.85 billion along with other costs for future exploration. Inalum had to borrow from 11 banks for the acquisition.

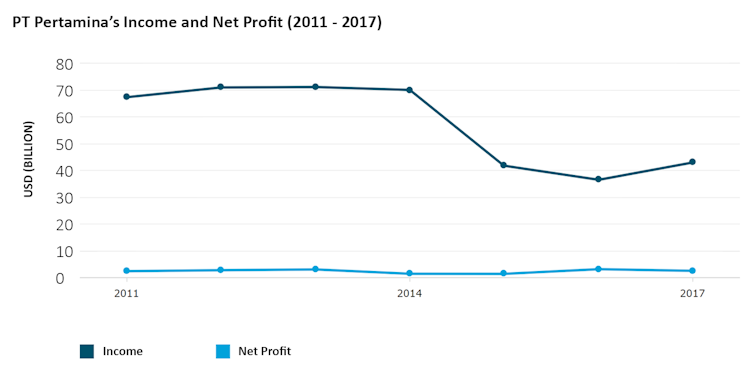

Many fear Pertamina may encounter the same problem as the Rokan deal will be a long-term financial burden on Pertamina’s performance.

In 2017, Pertamina’s net profit dropped by 19% to Rp33.7 trillion (US$2.3 million) on higher costs.

The return of the old model

The nationalist agenda behind the Rokan block and Freeport deals reflects the bigger picture of Indonesia’s current development strategy.

Analysts like Edward Aspinall, Eve Warburton and Jeffrey Wilson have argued that the Indonesian government is bringing its business sectors closer to its nationalist agenda of past decades.

The sentiment against liberal economy policy within Indonesia’s society and the global economic slowdown have motivated the government to implement such inward-looking economic policies.

This nationalist agenda is very strategic for leaders to secure votes. President Jokowi is seeking a second term in next year’s presidential election.

To support his candidacy, Jokowi seems to have promoted his nationalist agenda. The Freeport and Rokan block deals are examples of how he defended national interests in strategic sectors.

Political scientist Eve Warburton, from the Australian National University, said the nationalistic agenda under Jokowi was a “new normal”.

Indonesian leaders tend to come up with populist and protectionist agendas to secure votes. These agendas include fuel and electricity subsidies as well as cash for poor people.

These policies were adopted under Jokowi and former president Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono.

Jokowi’s mixed model

Jokowi’s economic policy, however, is not purely nationalistic. Some of his economic policies have been driven by an outward-looking strategy as well. An outward strategy promotes foreign investment and privatisation to spur economic growth.

While protecting national interests in Rokan blocks and Freeport mines, Jokowi also pushes for foreign direct investment in infrastructure projects. Having both strategies in place, Jokowi’s economic policy is a mixed model.

Jokowi’s mixed model is not a novel approach in Indonesia. Throughout the New Order regime, Suharto practically led Indonesia under a dualistic economy. In his early days, Suharto put his trust in prominent Indonesian economists who advocated outward-looking strategies.

Suharto implemented a series of economic reform packages. These included investment procedures that opened up some sectors to foreign direct investment.

Despite his liberal policies, Suharto was also known for his nationalistic policies. Under his administration, imports were decreased and the agricultural and energy sectors gained some protections. He also made local private businesses a part of national industrial policy.

Learning from the past

So what kind of economic policy works best for Indonesia?

The mixed economic policy may be best at the moment. While it serves the national interest, it also allows some space for reforms and opportunities for international cooperation.

Putting aside the continued debates over the Rokan block, let’s see what the government and the company will do next.

It is important to note that a nationalist agenda should serve the public interest rather than elites and particular groups.

The government also needs to be more careful in making any economic policy, because these come with long-term implications.

For example, Suharto’s bad economic policy against the background of the Asian financial crisis in 1998 led to political and social unrest that ended his regime.

Finally, the public needs to keep a close watch on the government’s commitment to economic reform and better corporate governance, including the transparency of state-owned firms.

***

Farahdiba Bachtiar, PhD Candidate, RMIT University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.