Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsInsight: Are democracies equipped to handle fast-moving economic crises?

Freedom House noted in March 2020 that we are entering the 14th year of consecutive decline in the health of democracy globally. Tracking the fate of the “third wave democracies”, Mainwaring and Bizzarro found that of the 91 democracies that emerged from 1974 to 2012, 34 experienced democratic breakdowns, while the quality of democratic practices stagnated in about 28 countries.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

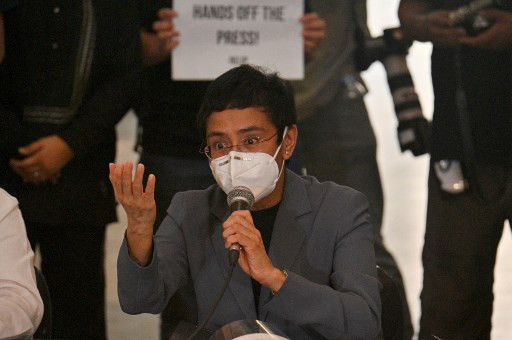

Philippine journalist Maria Ressa speaks during a press conference after attending the court's verdict promulgation in Manila on June 15, 2020. - Ressa was convicted on June 15 of cyber libel and sentenced to prison in a case that watchdogs say marks a dangerous erosion of press freedom under President Rodrigo Duterte. (AFP/Ted Aljibe )

Philippine journalist Maria Ressa speaks during a press conference after attending the court's verdict promulgation in Manila on June 15, 2020. - Ressa was convicted on June 15 of cyber libel and sentenced to prison in a case that watchdogs say marks a dangerous erosion of press freedom under President Rodrigo Duterte. (AFP/Ted Aljibe )

C

OVID-19 arrived not only amid a retreat of multilateralism and rising strategic rivalry between the United States and China, but also at a time of ongoing worrying trends for democracies worldwide.

Freedom House noted in March 2020 that we are entering the 14th year of consecutive decline in the health of democracy globally. Tracking the fate of the “third wave democracies”, Mainwaring and Bizzarro found that of the 91 democracies that emerged from 1974 to 2012, 34 experienced democratic breakdowns, while the quality of democratic practices stagnated in about 28 countries.

In fact, several of those regimes may now be considered democracies in name only. Illustrative examples include Putin’s Russia, Orban’s Hungary, Erdogan’s Turkey, and closer to home, Duterte’s Philippines.

Despite significant achievements since 1998, in recent years Indonesia appears to be catching up with this global trend. The practice of democracy in Indonesia has faced challenges such as violence and discrimination against minorities, arbitrary use of blasphemy and defamation laws to curb free speech, separatist tension in Papua and systemic corruption. Developments that have unfolded since COVID-19 appear to reinforce this trend, as shown, among other examples, by attempts to silence the strongest forms of government criticism during the pandemic.

We argue that while democracies have many different features that could both hurt and help during an ongoing crisis, democracy works better when there is a well-informed and open society. Now, more than ever, Indonesia needs guardians of economic policies to be critical citizens that help ensure that policies formulated to handle the crisis are truly in line with public interest.

In the context of COVID-19, if the balancing act between containing the disease and minimizing the economic costs is not tread carefully, a public health crisis could quickly wreak havoc on the economy, which in turn, would erode support for democracy

Recent public opinion polls suggest that something similar might be taking place in Indonesia, although we should note that correlations do not necessarily imply a causal relationship. Perceptions of economic deterioration moved in tandem with the slump in perceptions of democratic performance.

According to a survey by Indikator Politik Indonesia, respondents who stated the national economy was “bad” or “very bad” jumped from 24 percent in February 2020 to 81 percent in May 2020, during the lockdown. This mirrored the respondents who answered they were either “satisfied” or “very satisfied” with the way democracy works, falling from 75 percent in February 2020 to 49 percent in May 2020.

While theoretical conceptions of democracy highlight the maxim of free, fair and competitive elections and guarantees for civil liberties (e.g. freedom of expression and association), the aforementioned poll suggests that for Indonesian citizens, perhaps democracy is more closely associated with good governance, and the latter’s failings make citizens view the former unfavorably.

If we look at the history of modern Indonesia, there is a risk that economic dislocations could escalate into social and political instability. Understandably, a large part of the society has been suddenly thrown into poverty, especially with those working in the informal sector with weak social-safety nets abruptly experiencing income losses.

As such, the swift and comprehensive fiscal policy responses to the pandemic once the government realized Indonesia would not escape the coronavirus outbreak (around early to mid-March) should be commended. That is, the policies that come to about Rp 700 trillion (US$47 billion) correctly prioritize scaling up healthcare (including testing and health insurance) and ramping up social assistance to the poor and those vulnerable to “enter” into poverty.

With these programs estimated to widen the budget deficit to 6.3 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) in 2020, in a move unprecedented since 1998, Bank Indonesia (BI) is now monetizing the national government’s debt, providing direct financing (i.e. buying government bonds in the primary market) for Rp 397.5 trillion of the package, especially for spending related to health care and social safety nets. This is on top of executing the more traditional monetary actions such as lowering interest rates and intervening to strengthen the exchange rate.

It is too early to ascertain whether these policies — good on paper as they may seem — will be adequate for the challenges at hand. Like with any expedited large-scale programs, there are always risks on the horizon.

Under the 1999 BI Law, there are clear limitations on the ways in which BI can lend to the government. The limits are there for a reason: history shows that hyper-inflation episodes almost always originate from discretionary and excessive government spending that is accommodated by central banks printing money.

One could argue that this is a bold step and that the risks of runaway inflation seems low given the weak aggregate demand since COVID-19. However, it should not be dismissed that allowing BI to finance the government deficit constitutes a departure from economic orthodoxy.

Indeed, Regulation in Lieu of Law (Perppu) No. 1/2020, temporarily relaxes the above-mentioned limitations. However, it should be abundantly clear to the public that there be an exit strategy of just how long BI will continue to play a role in the financing of the COVID-19 response. Without it, the market will continue to be concerned about BI’s independence.

The credibility of the government and BI will be put to the test when the scheme period ends, the economic situation improves and whether these exceptions will be extended. Then we can clearly judge whether the moniker “guardians of good economic policies” is earned.

-------

Puspa Amri is assistant professor of economics at Sonoma State University and regular visiting fellow at CSIS Indonesia.

Rocky Intan is researcher at the Department of International Relations, CSIS Indonesia.

The original article was published in CSIS Commentaries.