Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsA story in wax: When batik connects Indonesia and indigenous Australia

The batik-making environment in remote desert communities in Australia is often the chaotic outdoors, where children and dogs run about and the weather can range from freezing cold to above 40 degrees Celsius.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

I

ndonesian batik artist Agus Ismoyo recalled a chance meeting in Yogyakarta over 30 years ago that eventually led him to travel to the remote desert lands of Australia. That day, Ismoyo gave directions to the late Australian curator, Michael O’Ferrall, in Yogyakarta.

O’Ferrall was actually looking for another artist, but further conversations and meetings between him and Ismoyo ensued nonetheless and O’Ferrall’s interest in Aboriginal art struck a chord with Ismoyo’s preference for traditional arts over pure modern aesthetics.

“I was getting a bit bored with the aesthetics of art,” Ismoyo said in an interview.

“I wanted aesthetics to have a story behind them, so I was drawn closer to traditional batik art [...] I felt I can learn further with my ancestors and all that.”

Yet Ismoyo, founder of the Brahma Tirta Sari Batik Studio along with his wife, Nia Fliam, felt a certain alienation due to his preference.

“I was confused, because tradition is something that is considered to be in the past, in this modern age-something that needs to be left behind.”

Thus, both him and American-born Fliam were intrigued by O’Ferrall’s knowledge of Australian Aboriginal art.

“The conversations with Michael made me think that in this world with so many traditions, it would be very exciting for one tradition to meet the other [...] We started exploring the idea of collaborating with Aboriginal people,” Fliam said.

The meeting led to more introductions, including one with James Bennett, currently the curator of Asian Art in the South Australian Art Gallery, and Jenny Green, a linguist who has worked with indigenous peoples of Central Australia since the 1970s.

It did not take long for the plan to materialize. In 1988, Ismoyo and Nia had their first workshop, which included the Australian Aboriginal art community. They then went to the Northern Territory and held numerous workshops in communities there.

In 1994, 10 women from the Urapuntja Utopia community came to Yogyakarta for a workshop and to work on pieces for their joint exhibition, "Hot Wax". A year later, the couple traveled in the outback for three months, giving workshops in remote communities for the Northern Territory Department of Education.

In 1999, eight of the Urapuntja Utopia artists agreed to collaborate with Ismoyo and Nia for the Asia-Pacific Triennial. The experiences of living and working in Aboriginal communities made their marks in the couple’s hearts.

“I felt as if I was enveloped by nature,” Ismoyo recalled.

When he arrived in the communities, he often refrained from moving straight to business. Instead he took part in their cultural events, such as hunting and eating together.

“The Aboriginals had the sensitivity, evident in them singing the songs of their ancestors; they believe nature is their ancestor. It is such a delicate law,” Ismoyo said.

The couple described how they felt welcomed, even accepted as part of the family by the women they worked with in the communities, most of whom, sadly, have passed away since.

“They patiently introduced their laws to us. I think it was a life-changing experience,” Fliam said.

Desert patterns: A batik piece titled Red Dirt was born out of a collaboration between Indonesian and indigenous Australian artists. (Courtesy of Nia Fliam/-)Renowned Aboriginal artist Barbara Weir still remembered the trip to Indonesia when the writer visited her early last year.

Since the batik trip, Weir has traveled to other parts of Asia and Europe and her works. Most of them are acrylic paintings that have been displayed in a multitude of countries, including Japan, France and the United States.

Even before the collaboration with Brahma Tirta Sari materialized, several Aboriginal communities were already familiar with batik techniques.

Since the 1970s, a number of Aboriginal artists were already learning batik techniques, exhibiting their batik works and even going to Indonesia to learn more about the art form.

According to a chapter featured in the book Raiki Wara: Long Cloth From Aboriginal Australia and the Torres Strait, Aboriginal artists living in the Ernabella community, South Australia, have been learning batik since 1971.

Ernabella is also known as Pukatja. It is located near the South Australia and Northern Territory border and its latest population was recorded as 497 in the 2016 Australian Bureau of Statistics Census.

The chapter’s author, National Gallery of Victoria’s senior curator for Indigenous arts Judith Ryan, wrote how in the 1970s and 1980s, batik technique spread across Aboriginal communities in Australia, including Yuendumu and Utopia in Northern Territory.

The region of Utopia covers thousands of square kilometers of land located some 230 kilometers northeast of the town Alice Springs. The population has been quoted by the National Museum of Australia to be around 800. It is the birthplace of artist Barbara Weir.

Batik nostalgia: Artist Barbara Weir in Alice Springs holds up a photo of her younger self and a long batik cloth. (Courtesy of Dina Indrasafitri/-)Suzanne Bryce, who is currently living in Alice Springs and working in the field of nutrition, was one of the first art workers to be involved in the Utopia batik scene. Like many young women of her generation back then, she was fascinated by batik and the idea of traveling to places such as Indonesia, which, at that time, was seen as relatively new and unexplored.

She went to Indonesia to learn the craft before returning to Australia and traveling to remote communities.

“I started out as somebody who could [help] women to make crafts,” Bryce said.

“In 1974, I came from Melbourne with a box of naphthol dyes and a sewing machine and went to an aboriginal community. I've mostly been here ever since.”

Most batik facilitators in remote communities witnessed unique adaptations of the art form because of different climates and social environments. Most of the time, it was impossible to maintain the traditional Indonesian technique of applying the designs carefully using canting (a pen-like instrument consisting of a small copper reservoir with a spout on a wooden handle) and hot wax on stretched fabric.

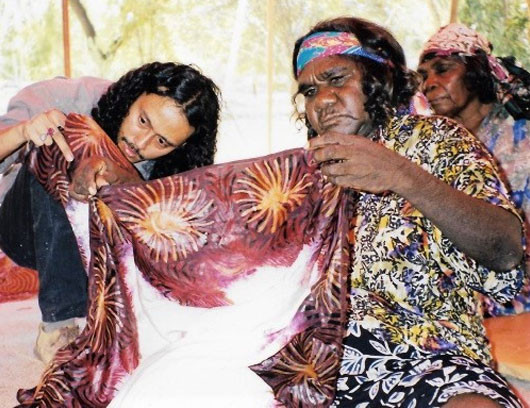

Indigenous Australian batik artists are known to be more spontaneous and bolder in their batik-making, applying the design using a brush instead of a canting, for example, or placing the cloth directly on their laps.

Sand might make its way into the wax, causing blots or cracks, yet these were incorporated into designs that can range from purely decorative or referring to ancient stories.

For some Aboriginal artists in the early days, batik equipment were simply one of the first introduced art materials, along with things such as brush, paper and paint. Some artists would simply take their inspiration from body paintings or marks for ceremonies or drawings on the sand, done when telling ancient stories or laws.

At Ernabella, inspirations for batik designs were partly drawn from children’s pastel drawings.

One artist from Fregon, as told in the book Across the Desert: Aboriginal Fabric from Central Australia, even humorously recalled how surprised Indonesian artists were when they saw how confident the Aboriginal women were in applying hot wax directly onto fabric without using stencils.

These days, most Indigenous Australian artists have moved on to acrylic on canvas as their main medium, due to the method’s practicality. However, Aboriginal Australian batik have succeeded in making a name for itself, at least from the 1970s to the 1990s, and many successful painters started out as batik artists.

Several notable exhibitions of Indigenous Australian batik include “Across the Desert” and “Raiki Wara” in the National Gallery of Victoria; “Hot Wax: An Exhibition of Australian, Aboriginal and Indonesian Batik” at the Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory; the collaborative work of Urapuntja Utopia and Brahma Tirta Sari for the Asia-Pacific Triennale and the touring exhibition “Utopia: A Picture Story”. (ste)