Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsBuilding a mosque in Japan

While the commoditization of religion is generally welcomed as it drives the economy, it becomes a problem when religion transgresses into politics

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

W

hile the commoditization of religion is generally welcomed as it drives the economy, it becomes a problem when religion transgresses into politics.

The arrangement of public life is the domain of politics and should be guided by civic principles, whereas religion concerns the inner lives of its adherents.

Everybody knows, however, that to disentangle politics and religion is a daunting task.

In this regard, an off-the-cuff statement recently made by Constitutional Court chief Mahfud MD on the guarantee of citizen’s rights to choose their religious and ideological beliefs should be greeted as a glimpse of hope in the darkness.

Mahfud is certainly not alone in his attempt to resolve the convoluted nexus between religion and politics in this country.

The domination of religion in public life is undeniably strong and we should work hard if the border between religion and politics is to be delineated.

Arief Budiman, our intellectual doyen, gave a very illustrative example of how futile it is to isolate public space from the intrusion of religion.

In his memoirs, published in Tempo magazine (July 29), Arief together with a group of young progressive lecturers at Satya Wacana Christian University in the Central Java town of Salatiga, rejected the university’s plan to build a church inside the campus.

They said it would be more useful for the university to allocate the money for educational facilities as Christianity would automatically flourish if the university produced good academic work.

Arief and his colleagues’ eventually failed in their attempts.

We know that erecting places of worship in offices, government or private, was very common under Soeharto’s New Order and it has unfortunately been accepted as normal.

As religiosity lies within the inner life of an individual, problems will arise if it is courted by power as a source of political arrangement in public life. The domination of power in the hands of a particular religious group threatens equal relationships in a pluralistic society.

The state has, since the Soeharto era, fallen into the trap of being unable to separate religion from politics, as it continues to court religion as the social basis for its political legitimacy.

The level of religiosity is not always in accordance with religious appearance in public life. Komaruddin Hidayat, the rector of Syarif Hidayatullah Islamic State University, in his article in Kompas on Nov. 5, 2011, said that the seemingly glittering Islam in Indonesia did not necessarily result in better practices in this predominantly Muslim society.

The Muslim scholar was responding to the findings of a comparative study “How Islamic are Islamic Countries?” which surprisingly revealed that the best practices of Islamic values were not found in Islamic countries but in non-Muslim countries, such as New Zealand, Luxemburg and Canada.

In order to get a better perspective, Japan is perhaps a good example of how religion is perceived and practiced in public life.

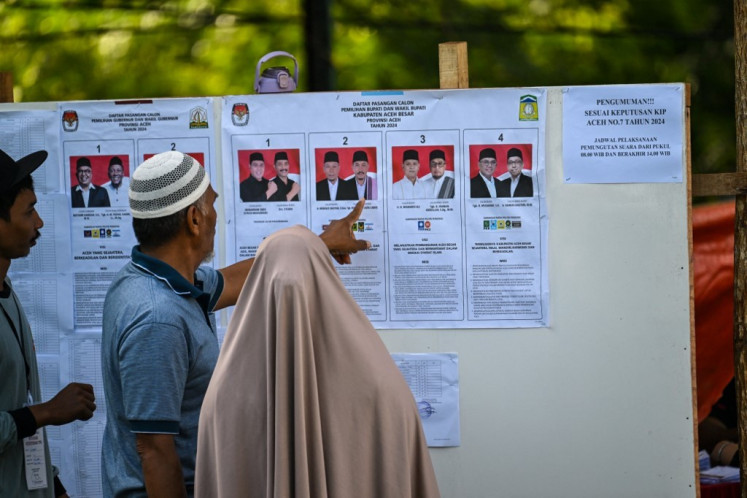

Last year, during my research on the life of migrant communities in Fukuoka, I observed how foreign workers and students, who were mostly Muslim, managed to build a small but beautiful Fukuoka Mosque.

Based on my interviews with the Muslim leaders who played an important role in the construction project, I discovered an intriguing phenomenon of how the Japanese actually perceived religion in their life.

The most difficult part of constructing the mosque, apart from raising the funds, was to gain support from the local people in the Japanese neighborhood where the mosque was going to be built.

In Japan, as a result of the US occupation following World War II, religion has to be separate from the state. The US knew well how strongly religiosity influenced nationalism in Japan.

In the case of the mosque construction, the Fukuoka government therefore could not interfere in whether or not a place of worship could be erected.

It only inspected whether the construction plan was in line with safety procedures, the land was legally owned and the building was located in the proper government zoning jurisdiction. As soon as all the requirements were met, the mosque construction could begin.

It was the approval of the neighborhood that was the big issue. I learned it took the Muslim community a long time to win the consent of people around the area where the mosque would be built.

As I wondered why the Japanese neighborhood finally agreed to the mosque construction, I interviewed several Japanese experts at the center for religious studies at Kyushu and Fukuoka University.

My endeavor revealed interesting findings. Among others, I discovered that the Japanese highly respect religiosity, while religious rituals can be adhered to more flexibly.

It is no wonder that the Japanese accept religious differences without any problems. What matters to the Japanese it seems, is how we foreigners should behave. They strongly trust their government to provide security to every citizen.

This is contrary to what happens in Indonesia. There is a tendency to let religious practices enter the public domain.

State officials frequently confuse the public by mixing up religious ideology and government policies in their statements concerning public matters.

I am not sure how long we can actually endure a public life so full of such hypocrisy.

The writer is a researcher at the Research Center for Society and Culture, Indonesian Institute of Sciences (LIPI), Jakarta.