Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsGlobal minimum tax: Complex tax incentive reform or another policy in limbo?

This is a groundbreaking yet daunting development for the country’s fiscal framework.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

I

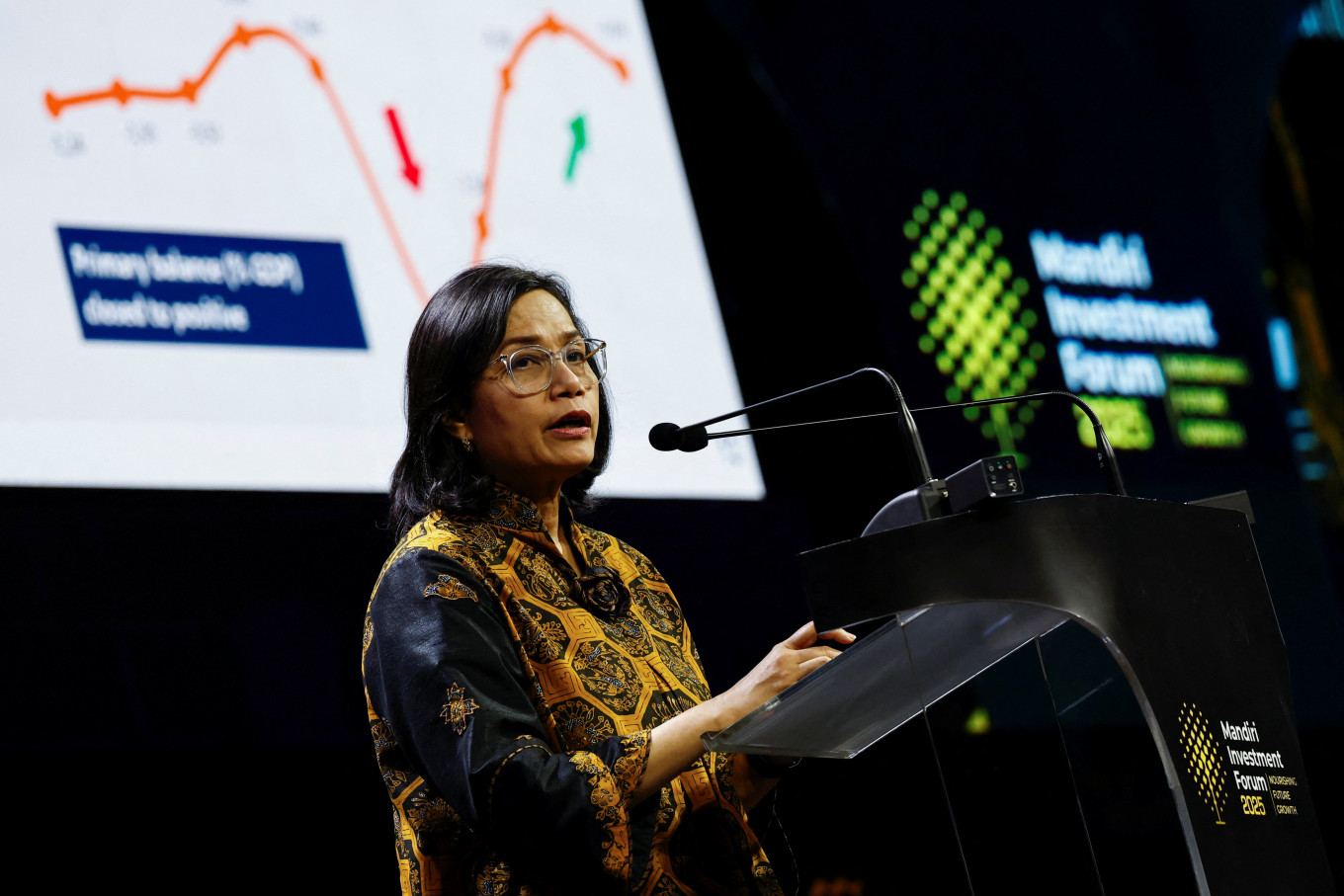

n mid-January, the government published the much-awaited Finance Ministerial Regulation No. 136/2024, officially marking the beginning of the Global Minimum Tax (GMT) era. As a tax professional, I find this a groundbreaking yet daunting development for the country’s fiscal framework. It represents Indonesia’s alignment with global tax reform but raises significant questions about its real-world impact, particularly for developing economies like ours.

GMT is a global initiative to curb tax avoidance by multinational enterprises, spearheaded by the OECD Inclusive Framework, of which Indonesia is a member. GMT acts as a safety net to ensure multinational companies contribute their fair share of taxes, no matter where they operate.

If a company pays little to no tax in one country, another jurisdiction, whether it is the parent company’s jurisdiction or the jurisdiction of other entities within the group, can step in to collect the difference, ensuring a global minimum rate of 15 percent. At first glance, the idea seems noble, particularly for medium-to-high-tax jurisdictions like Indonesia, as it promises to level the playing field. But a closer look reveals deeper complexities.

Developing countries like Indonesia have had little choice but to join the GMT. The message is clear: refuse to comply, and your tax incentives, designed to reduce tax to attract investment, will be neutralized by top-up taxes imposed elsewhere. I can’t help but recall the frustration expressed by Argentina’s Economic Minister Martín Guzmán, who described the situation as being forced to choose between “something bad and something worse”.

This raises a fundamental question: why were countries like ours backed into this corner? While the rhetoric of fairness dominates discussions, the reality often reflects unequal power dynamics. The so-called global consensus sometimes hinges on decisions by dominant economies. For example, progress on the GMT framework has, at times, stalled waiting for the US to give its approval (Vella, 2021).

Adding to this irony is the recent decision by new US President Donald Trump to sign an executive order withdrawing the US from the Pillar Two global tax deal. The US, once a key driver of the initiative, has now abandoned the framework it championed.

This decision exposes the fragility of the consensus and leaves countries like Indonesia grappling with its implementation. It is an obvious reminder that while powerful economies can opt out when it suits them, less influential nations bear the burden of the consequences.