Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsRehabilitation for Soebandrio: A reconciliation with history

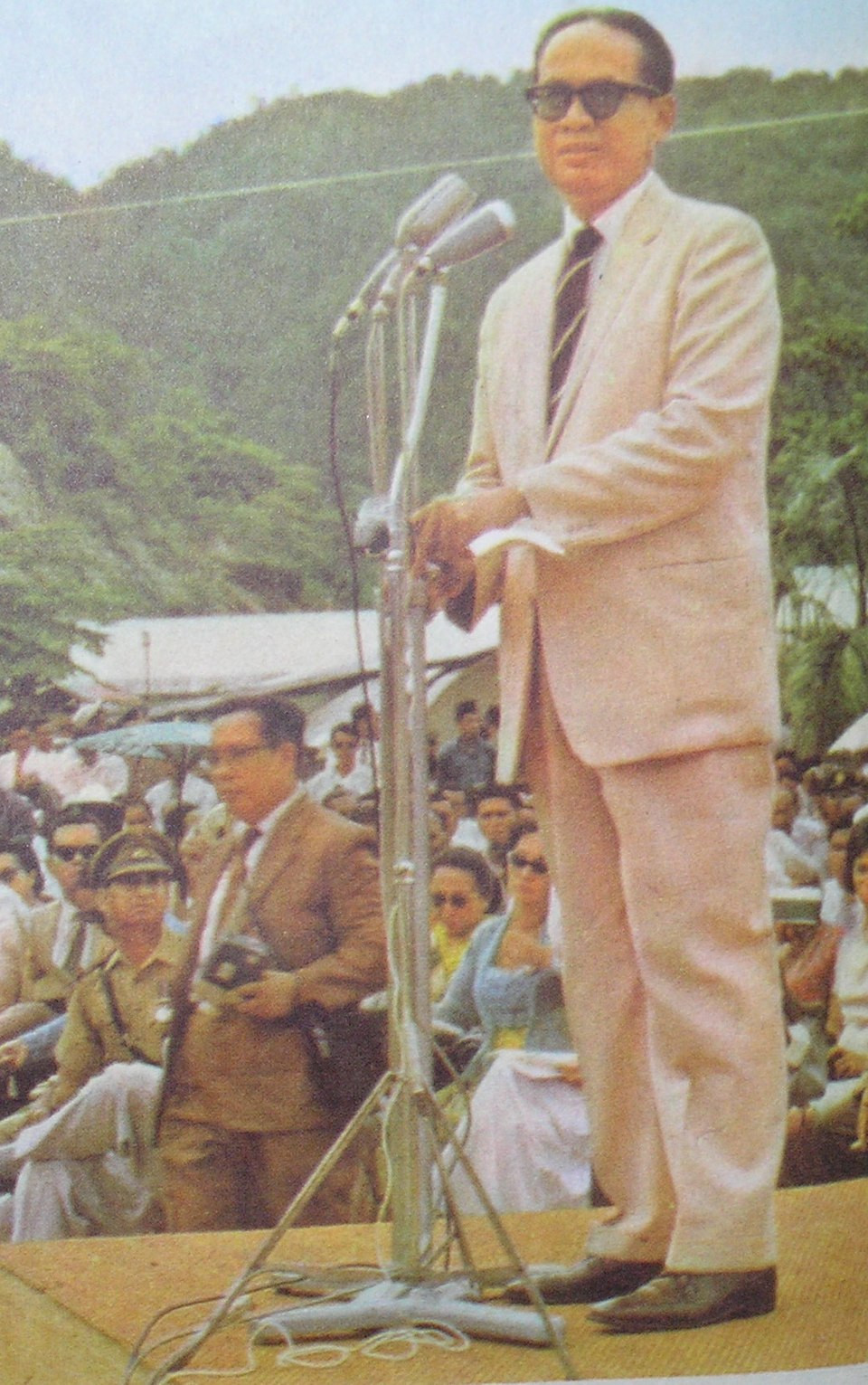

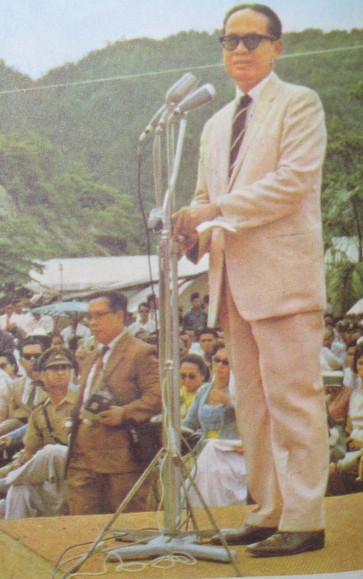

Soebandrio was a stalwart advocate for Indonesian sovereignty during the revolutionary period.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

T

omorrow’s launch of eight volumes commemorating the 70th anniversary of Yusril Ihza Mahendra, the Coordinating Law, Human Rights, Immigration and Correctional Affairs Minister, serves as more than a personal milestone.

These works, comprising biographies and testimonials, offer a window into the intersection of personal lives and national history. Having shared a residence with Yusril at the University of Indonesia’s Daksinapati Student Dormitory in Rawamangun, East Jakarta, about 50 years ago, I contributed a piece reflecting on our time there and his interactions with seminal figures such as M. Natsir, Syafruddin Prawiranegara and Soebandrio.

The connection between Yusril and Soebandrio is particularly poignant regarding the unresolved issue of legal rehabilitation. On Dec. 21, 2000, Soebandrio, the former deputy prime minister and foreign minister under president Sukarno, met with president Abdurrahman “Gus Dur” Wahid at the Presidential Palace to formally request the restoration of his rights.

While Gus Dur instructed Yusril, then the justice and human rights minister, to process the request, the administration's premature end following Gus Dur’s impeachment in July 2001 left the matter hanging in the balance. Now, 25 years later, the question remains: Will Yusril, in his current capacity as coordinating minister, propose this rehabilitation to President Prabowo Subianto?

Soebandrio’s life was defined by a profound tragedy: he spent nearly one-third of his ninety years behind bars. Imprisoned for 29 years following the aborted coup of Sept. 30, 1965, he became a primary target of the New Order’s effort to dismantle the Sukarno era.

Despite his long incarceration and subsequent death on July 3, 2004, the evidence supporting his involvement in the coup remains nonexistent. He was neither a member of the Indonesian Communist Party (PKI), which Soeharto blamed for the coup, nor associated with its affiliated organizations. Nevertheless, he was tried before the Extraordinary Military Tribunal (Mahmillub) and sentenced to death on Oct. 25, 1966.

The atmosphere of the trial, held in the building that now houses the National Development Planning Agency (Bappenas), was one of palpable oppression. As Soebandrio faced execution, international intervention arrived in the form of a protest from Queen Elizabeth II. Her Majesty’s plea was rooted in Soebandrio’s diplomatic history; he had helped establish the Indonesian diplomatic mission in London in 1946 and served as ambassador to the United Kingdom from 1950 to 1954. Consequently, his capital sentence was commuted to life imprisonment.