Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsMonetizing poverty: How algorithms harvest human desperation

Financial inclusion was supposed to be a lifeline; instead, it has become a dragnet. From predatory lending apps to algorithms that harvest "poverty as spectacle," the digital economy is transforming human desperation into a high-growth market.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

L

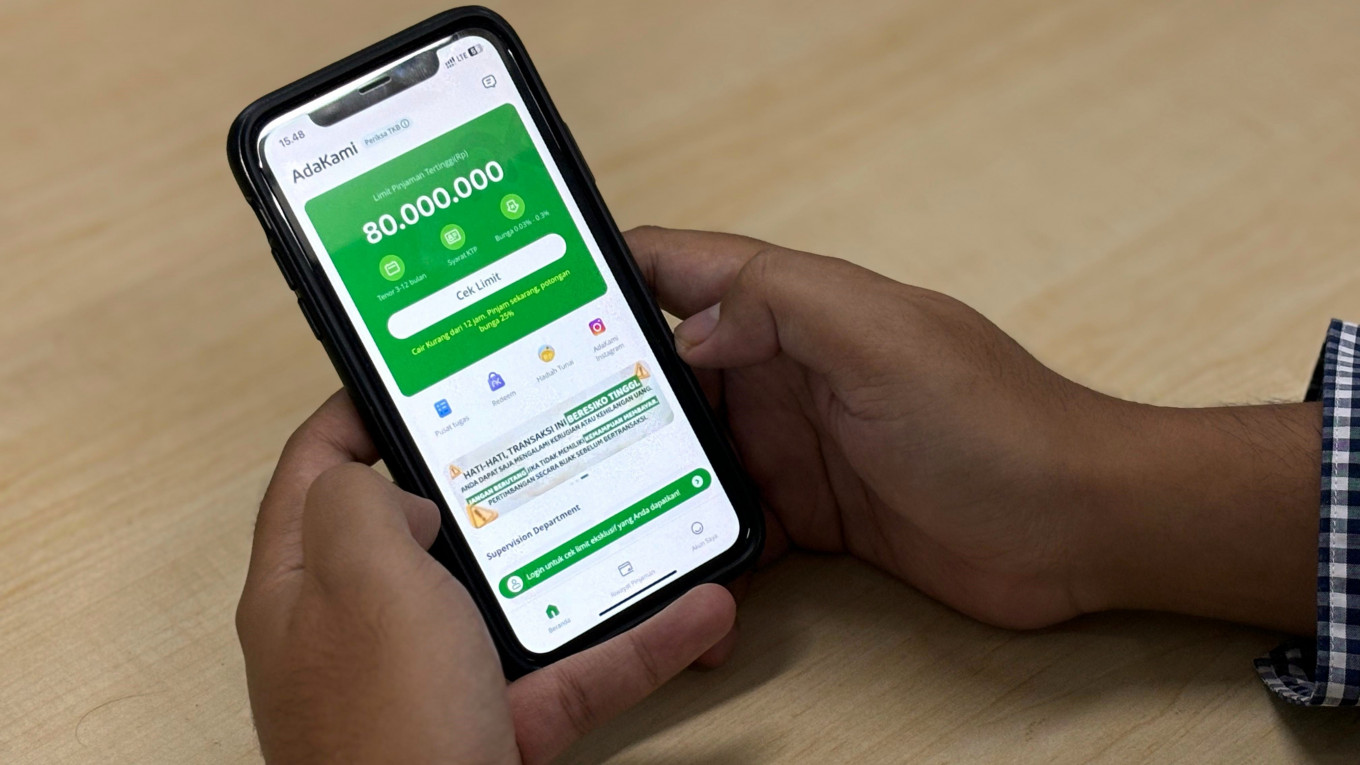

ate in the evening, an informal worker in the capital picks up his phone. Rice prices have ticked upward; his cash has run dry. With a few taps, he selects “disburse” on a lending app. There is no face-to-face judgment, no invasive questioning, only the sterile glow of a progress bar.

On that same screen, ads for “buy now, pay later” and “increased credit limits” appear like digital lifelines. Simultaneously, social media notifications provide a different kind of noise: viral clips of domestic strife, staged “survival” stories and people weeping for the camera, content engineered to hijack the viewer’s attention until the final second.

Hunger, anxiety and exploitation converge in a single space: a six-inch screen.

We often cloak this phenomenon in the sterile language of “financial inclusion”. But that term masks a predatory reality: poverty is being commodified. The daily shortages experienced by the poor are now raw materials, processed into streams of profit through service fees, penalties, commissions and the relentless pursuit of “engagement”.

Indonesia’s poverty rate stood at 8.25 percent (23.36 million people) in September 2025, according to the official data. However, vulnerability is not a binary state. It extends to the “near-poor”, those living on the razor’s edge, roughly 1 to 1.5 times the poverty line. In late 2024, this group accounted for over 68 million people.

This vast, vulnerable population has become the primary market for micro-digital credit. It is a market fueled by volatility. A minor shock, a medical bill, a slow week of odd jobs or rising fuel costs, is enough to force a shift from a “survival strategy” to an “emergency strategy.” In these moments of crisis, the digital economy finds its most effective conversion engine: urgent need. These borrowers do not lack “financial literacy”; they lack alternatives.

This is where the risk of inclusion becomes clear. Access without protective guardrails is not empowerment; it is a doorway to entrapment. When micro-loans are used to buy basic groceries rather than expand a business, default is not an accident, it is an inherent feature of the system’s design.