Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsIndonesia must pivot from headline growth to quality job creation

Despite demonstrable resilience, as long as economic policy prioritizes headline growth over the creation of high-quality jobs, the country risks leaving an entire generation of educated youth behind in a cyclic trap of informal jobs and wasted potential.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

A

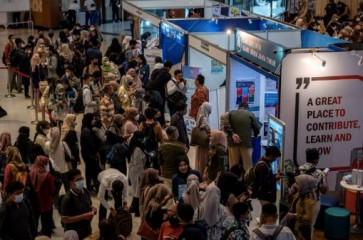

ddressing a sea of more than 9,800 new graduates at the University of Indonesia recently, Finance Minister Purbaya Yudhi Sadewa proclaimed that their commencement arrived at an auspicious time. With the national economy in an upswing cycle, the minister spoke of abundant job openings, even inviting them to apply for positions at the Finance Ministry for immediate processing.

However, for the graduates who preceded them, reality told a much starker story. Many found themselves adrift in a labor market that was either unable to absorb them or demanding skills fundamentally different from those taught in lecture halls.

For a growing number of university graduates in Indonesia, a new year does not mark a fresh beginning but rather another cycle of wasted potential. Each January, millions enter the market with high expectations, only to discover that demand for their specialized knowledge remains stubbornly stagnant. They are learning, quite painfully, that academic degrees no longer guarantee decent work.

National economic growth has been remarkably resilient for two decades, barring the pandemic years. Last year, the economy grew 5.11 percent, bolstered by agriculture, manufacturing and trade. Yet this expansion created only 1.9 million new jobs, a precipitous drop from the 4.8 million created in 2024. Furthermore, the majority of these were in agriculture and trade and consisted largely of low-skilled, low-paid positions.

Though the unemployment rate stood at 4.74 percent in 2025, this figure masks a deep structural imbalance. Unemployment among university graduates reached a troubling 9.6 percent, while the rates for elementary and junior high school graduates were significantly lower at 2.3 percent and 3.8 percent, respectively. This suggests that the economy is currently optimized for low-skilled, informal labor rather than the high-value roles a modernizing nation requires.

As of last November, some 85 million Indonesians worked in informal jobs, up from 71 million in 2019. In this sector, workers endure long hours with little pay, no job security and zero opportunity for upward mobility. This indicates that high economic growth has failed to produce high-quality jobs.

Perhaps most concerning is that youth unemployment (ages 15-24) has reached 16.3 percent, nearly 3.5 times the national average. This restless demographic represents more than 7 million people whose long-term exclusion from the workforce poses a legitimate threat to social and political stability.