Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsBounded rationality in the ever-changing cooking oil policymaking

Three changes in cooking oil policy could be an empirical case of bounded rationality.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

O

ver the last three months, the Trade Ministry has changed its policy instruments three times to stabilize the cooking oil price within a range the government believes will protect domestic consumers from the skyrocketing price of vegetable oils.

The measures have included the draconian policy of imposing a domestic market obligation (DMO) on producers, which amounts to 30 percent of their export volume sold at the DMO price, half the international market price.

The ever-changing policy instruments mirror "bounded rationality" in policymaking. Policymakers are bounded by cognitive limits and choose to adopt a tolerable course of action, rather than seeking the best possible. The instruments are adopted without perfectly knowing the uncertainty or the consequences.

Bounded rationality was coined by Herbert A. Simon in the mid-1950s. Simon was awarded a Nobel Prize in economic science in 1978 for his pioneering research into the decision-making process within economic organizations.

In A Behavioral Model of Rational Choice (1955), Simon challenged the perfect rationality assumption of “economic man” who hypothetically possesses complete information and knows all the courses of action, as well as the outcomes. Simon proposed a different assumption by describing humans as bounded by their own cognitive limits due to the inability to obtain or process all the information needed to make fully rational decisions. Instead, humans seek to use incomplete information to produce a satisfactory result, or one that is "good enough."

In his Nobel memorial lecture, Simon hypothesized that bounded rationality was largely characterized as a residual category – rationality is bounded when it falls short of omniscience. And the failures of omniscience are largely failures of knowing all the alternatives, uncertainty about relevant exogenous events and an inability to calculate consequences.

Bounded rationality decision making is about searching and “satisficing” – a combination of satisfying and sufficing – or achieving a satisfactory outcome. Satisficing means the tendency of decision-makers to select the first alternative that meets the aspiration as to how good an alternative should be. Once a choice meeting the aspiration level is found, the search stops.

Three changes in cooking oil policy instruments could be an empirical case of bounded rationality. The policymakers formed aspirations, then searched for alternatives and satisficing. Once the government found a "good enough" alternative to meet the aspiration, it stopped searching for others. The alternative was chosen without full understanding of the uncertainty of exogenous events and the consequences of applying it. When the adopted alternative was ineffective, the second alternative was sought after and chosen. Alas, the second alternative failed, and the government searched for the third.

At the beginning, the aspiration was to reduce and stabilize the cooking oil price. On Jan. 19, a single price policy of Rp 14,000 (90 US cents) per liter was adopted with the support of Rp 7.6 trillion in subsidies but this measure was not effective.

The week after, on Jan. 26, the policy was replaced with the imposition of changes to the DMO and domestic price obligation (DPO) for crude palm oil (CPO) and olein plus a maximum retail price. This measure also was not effective because the government did not assign a special agency to manage the market control mechanism.

Those two policy instruments might have been the only available alternatives that the government could find. Constrained by such a limitation, policy instruments became sub-optimal. The government failed to discover the uncertainty about exogenous events, i.e. the volatility of the international CPO price. It was also unable to calculate the consequences of the instruments, i.e. a cooking oil shortage when supply fell sharply after the maximum price was imposed.

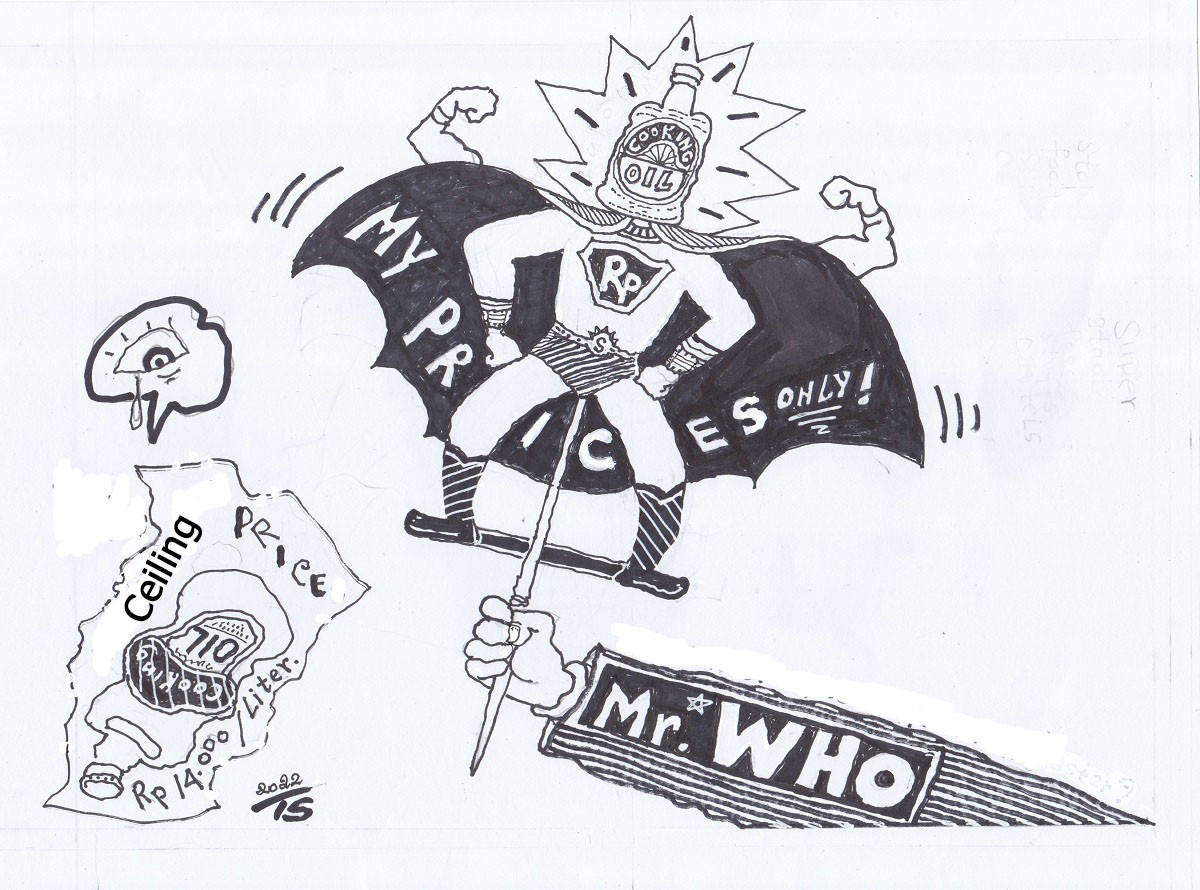

The government must also deal with an oligopolistic seller's market for cooking oil. A few producers who operate integrated palm oil plants dominate the domestic market, where demand exceeds supply and this empowers sellers to dictate prices. Any government intervention in the market would face strong resistance from the oligopolists. Unlike the government, which must balance the interests of producers and consumers, the producers and distributors have flexibility to act selfishly and rationally. They know how to choose alternatives, mitigate uncertainty and calculate consequences of strategies for profit maximization.

The DMO mechanism and the fixed range of prices for cooking oil was abolished on March 16 and replaced with the imposition on palm oil exports of a progressive windfall and export tax amounting to US$575 per ton. The price of bulk cooking oil was fixed at Rp 14,000 per kilogram and any gap between this fixed price and the production cost would be covered by the government with subsidies funded by the Palm Oil Support Fund Agency (BPDPKS). The government also abolished the fixed range of retail prices and freed the prices of packaged cooking oil on the open market.

As soon as the fixed retail prices were liberalized the shelves of retailers and supermarkets were overloaded with stock but at prices twice as high as the previously fixed retail prices.

There is a risk that the commodity-based subsidy scheme, provided to producers to enable them to sell at the Rp 14,000 maximum price, will not optimally reach the targeted beneficiaries. Higher-income consumers might shift to buying bulk cooking oil instead of the packaged product or traders might buy bulk cooking oil and repackage it to be sold at the free market prices.

Many analysts and even such multilateral institutions as the World Bank have suggested that instead of providing commodity-based subsidies (for producers) the government would be better providing cash transfers directly to low-income consumers and letting them choose where they will spend the money. This better targeted subsidy scheme would minimize the risk of misuse, given the inadequate institutional capacity of the government to effectively implement the market-control mechanism.

***

The writer is a managing partner at Trade-off Indonesia economic and business advisory services. The views expressed are his own.