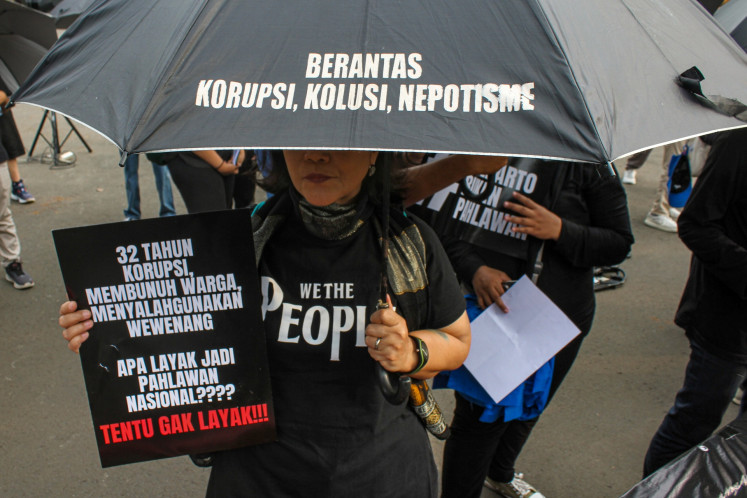

Understanding corruption and three simple lessons to prevent it

Corruption has plagued societies for thousands of years and its recurrence is rooted in human greed.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

T

o combat corruption effectively, we must first grasp the nature of the crime and how it operates, enabling us to draw crucial lessons that will help prevent its recurrence in the future.

Corruption can be analyzed from multiple angles, but let us delve into three fundamental areas: corruption throughout human history, corruption and government and corruption and law enforcement. By examining these aspects, we can extract vital insights for the fight against corruption.

Recent graft cases in Indonesia have raised serious concerns. With officials, even at the ministerial and Supreme Court justice levels, being involved, the sense of justice is coming under threat. Interestingly, corruption is not a new phenomenon. Its roots can be traced back over 4,000 years.

Around 2100-2050 BCE, in the ancient Mesopotamian city of Ur (present-day Iraq), King Shulgi issued the Code of Ur-Nammu, comprising 57 laws aimed at maintaining order and justice. Notably, it included a stern crackdown on corruption, bribery and abuse of power. Beside corruption provisions, the code also regulated property, wealth, marriage and trade laws. In a sense, it was similar to the omnibus laws introduced by President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo.

Fast forward a few centuries, around 1755-1750 BCE, King Hammurabi issued the Code of Hammurabi, in Babylon. It had 282 laws focusing on justice and protection of the weak. The code also specifically targeted corrupt judges who accepted bribes and delivered unjust verdicts. Like Ur-Nammu, the Code of Hammurabi served as an omnibus law.

The takeaway from these ancient histories is clear, that corruption has plagued societies for thousands of years and its recurrence is rooted in human greed. Our first lesson lies in strengthening anticorruption institutions, encompassing laws, enforcement agencies and supportive government policies. The leadership of Ur-Nammu and Hammurabi serves as a timeless benchmark.

One of history's most impactful corruption cases involving the government was the Watergate scandal in the 1970s, which led to the resignation of Richard Nixon as president of the United States.

This notorious scandal started with five individuals attempting to break into the Democratic National Committee headquarters at the Watergate complex in Washington, DC. The subsequent investigation unveiled a vast corruption network, encompassing illegal campaign funding, obstruction of justice, abuse of power and the infamous "White House Plumbers" covert group. Public vigilance, especially through media scrutiny, eventually led to the resignation of high-ranking officials, including Nixon.

A parallel can be drawn between this case and the current base transceiver station (BTS) corruption case in Indonesia, which is now being heard in court. The “corruption web” also involves many parties, mostly high-level, in this case.

However, unlike Nixon and his associates who resigned, some in Indonesia are attempting to regain their ill-gotten gains.

What is the next lesson we can learn? The second lesson is clear: corruption and power go hand in hand. The fight against corruption requires unwavering efforts to enhance government transparency, accountability and rigorous oversight. Public participation, especially through the media, is a crucial weapon in this battle.

The Code of Hammurabi contains intriguing provisions regarding corruption, witnesses and judges. Notably, Article 4 stresses the integrity of witnesses, imposing penalties if they accept bribes for their testimony. Translated by Robert Francis Harper's English (1901), Article 4 states: "If a man (in a case) bear witness for grain or money (as a bribe), he shall himself bear the penalty imposed in that case". So, if a witness is found to have accepted a bribe, he/she will bear criminal punishment for the case they testified in.

Similarly, Article 5 deals severely with judges altering their judgments, ensuring they face harsh consequences. It states: “If a judge pronounce a judgment, render a decision, deliver a verdict duly signed and sealed and afterward alter his judgment, they shall call that judge to account for the alteration of the judgment which he had pronounced, and he shall pay twelve-fold the penalty which was in said judgment; and, in the assembly, they shall expel him from his seat of judgment, and he shall not return, and with the judges in a case he shall not take his seat".

This brings us to the third lesson. It centers on law enforcement agencies' critical role in combating corruption. Deterrence becomes a powerful tool, suggesting heavier penalties for corruption committed by law enforcement agents, adding one-third to their sentences. In severe cases, as in the Code of Hammurabi, law enforcement agents who accept bribes should face 12 times the punishment imposed. Furthermore, they should be dismissed from their position.

Too harsh? While it may seem so, these pale in comparison to the sense of justice shattered in society and the suffering endured by hardworking taxpayers who see their money squandered. Additionally, such corruption can impede Indonesia's path to becoming an advanced economy, diverting funds meant for development to personal or group gains.

Understanding corruption's historical context and its intersection with government and law enforcement enables us to draw invaluable lessons for an effective anticorruption strategy. By strengthening institutions, enhancing transparency and fostering public vigilance, we can forge a corruption-free future for our beloved nation. Together, let us stand united against corruption's insidious grasp.

***

The writer is an extramural fellow at the Tilburg Law and Economics Center (TILEC), the Netherlands, and a senior financial sector expert at the International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC.