Time for stringent standards for defamation

According to the recent report published by Smart Insight in 2016, in just one minute, there are 44.4 million message exchanges through WhatsApp, 3.1 million searches on Google and 3.3 million messages posted on Facebook.

Change Size

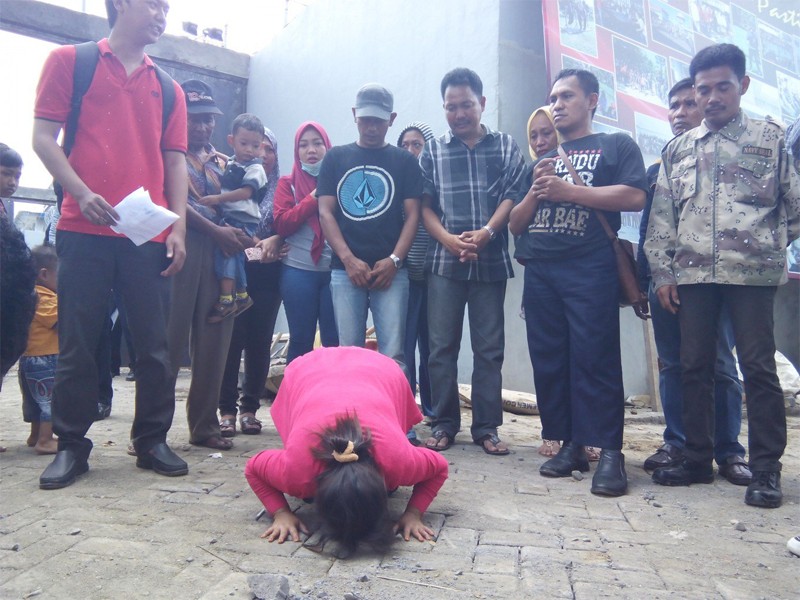

Yusniar, a defendant in a defamation case concerning a Facebook status, kisses the ground on Thursday after the Makassar District Court in South Sulawesi suspended her detention and changed it to city arrest. (JP/Andi Hajramurni)

Yusniar, a defendant in a defamation case concerning a Facebook status, kisses the ground on Thursday after the Makassar District Court in South Sulawesi suspended her detention and changed it to city arrest. (JP/Andi Hajramurni)

T

he use and misuse of the defamation clauses in the newly amended Information and Electronic Transactions (ITE) Law have reached an alarming level.

As most Indonesians spend at least four hours a day on the internet, as an active user of various social media platforms, one has to be more careful of the potential of becoming the next victim.

The defamation clauses arguably have become the most effective instrument for repercussion against any individual in any dispute, including the pretext for sending any individual to pre-trial detention.

During the ongoing race for the Jakarta gubernatorial post, for example, the misuse of these clauses has shifted into the political sphere, through which legal claims are extensively abused by the proponents of one candidate against the supporters of other candidates.

The abuse of the defamation clauses in politically sensitive situations will potentially increase as an exceptional volume of information is produced and exchanged through the internet with just one click.

According to the recent report published by Smart Insight in 2016, in just one minute, there are 44.4 million message exchanges through WhatsApp, 3.1 million searches on Google and 3.3 million messages posted on Facebook.

In particular, since the 2014 election, social media and the internet have become a major battle for canvassing votes in any election. In this context, the volume of information twisted and spun on the net is often much higher in volume than the reliable facts posted and disseminated by reliable sources.

The situation is made even worse as, according to recent data published by the Press Council, only 10 percent of total online active media outlets are registered under the council.

This means there are too many abal-abal (deceitful) news portals profiting from twisting information at the expense of the people’s right to information via the internet.

From the criminal jurisprudence perspective, the wording of the defamation articles contained in the ITE Law has substantial shortcomings. The drawbacks are twofold.

First, the wording of the articles is vaguely defined and lacks definite elements as to what constitutes defamatory action, both in terms of reputation and in the context of religion, ethnicity and race.

Therefore, there is huge room for subjective interpretation of the term, which in extreme instances can mean anything or nothing.

Defamation is very subjective, so anybody at any point of time can approach the police to instigate criminal charges against another party only based on his/her subjective feeling of being defamed or offended by another person’s expressions, with no evidence necessary as to whether, in fact, damage or potential damage to his or her reputation occurred.

The effect of such vague wording is evinced and was exploited in the recent case of Yusniar, a poor woman from Makassar who suffered from the disproportional use of pre-trial detention and was tried under the defamation clause of the (old) ITE Law for her comments about anonymous public officials on her Facebook account. We might not yet have forgotten the story of Dody, who was sentenced to 14 months’ imprisonment for news tagged on his Facebook wall.

There is a long list of cases in which the clauses have been jointly applied to a similar clause in the Penal Code as reprisal against those who are socially and/or economically weaker than those filing the criminal case with the police.

Second, the crime is considered a formal criminal offense under the Criminal Code (KUHP). This classification implies that any action, be it expression, gesture, written or verbal expression, can subjectively be considered defamatory by other parties.

In many cases, the trial hardly looks into the mental element of the crime (mens rea), that is, whether the intention of defaming exists. In other cases, which never reach trial, no remedy for suspects suffering from pre-trial detention is ever given.

As the hype for expressing everything online is there — thinking online reality as being not as real as the offline world — so “bad words”, which perhaps may never be said when offline, are posted in unprecedented volumes online, it is only time before more and more cases are fabricated under this charge.

This phenomenon is not specific to Indonesia. However, what makes it different here, perhaps, is the response to it. As the claim of defamation is considered highly subjective, various jurisdictions have begun to put stringent standards into place to prevent the abuse of the crime of obstructing the justice system.

Although in many countries defamation is still considered a crime, more rigid elements of crimes, as well as eligibility standards for exercising the claim, have been introduced.

The United Kingdom, for example, has introduced new requirements for any tort against action of defamation, such as the obligation to prove that reputation is seriously harmed. Also, to instigate a defamation case, the claimant has to prove financial damages occurred.

If the situation here goes unchecked, not only will the criminal law become a repercussion instrument against the socially and politically weak but also a serious threat to freedom of expression online. It is therefore timely to set more stringent standards on any claims based on the defamation clauses.

The responsibility rests with the police, prosecutors and particularly the judiciary powers to prevent the destruction of the justice system from massive abuse of these problematic articles.

---------------

We are looking for information, opinions, and in-depth analysis from experts or scholars in a variety of fields. We choose articles based on facts or opinions about general news, as well as quality analysis and commentary about Indonesia or international events. Send your piece to community@jakpost.com. For more information click here.