Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsEarly-childhood education: Ignoring present for future

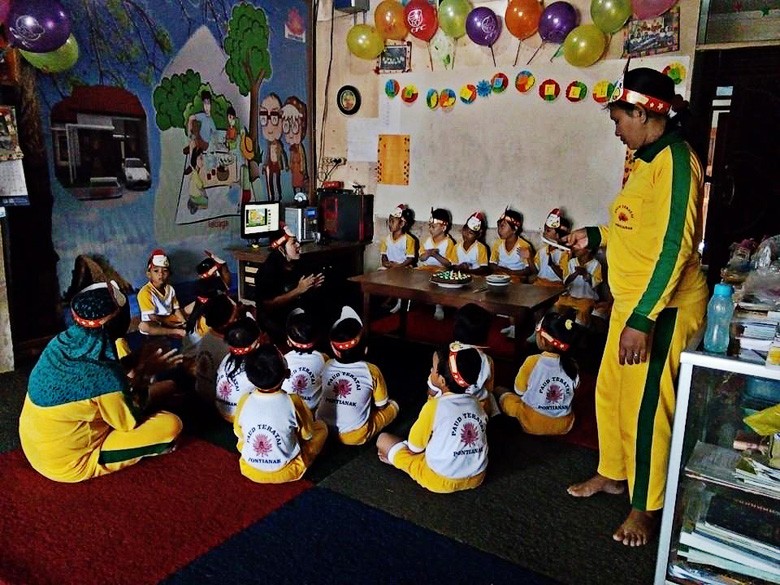

Early-childhood education (ECE), locally known as PAUD, has recently been included as part of the development strategy to suppress future inequality.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

M

any believe the early-childhood period is so critical and sensitive in shaping our future that it should be filled with the best learning opportunities. Early-childhood education (ECE), locally known as PAUD, has recently been included as part of the development strategy to suppress future inequality.

As a country suffering from a widening gap between the rich and the poor, Indonesia’s government, supported by development agencies, has been actively expanding ECE in poor regions and remote areas.

Here community mobilization has become the most popular method with communities running ECE centers using any available resources.

The aim is to minimize reliance on external resources to improve project sustainability. In Indonesia the results have been quite exceptional. With at least 100,000 new ECE centers built and managed by community members, the national preschool enrolment rate has jumped from 27 percent in 2007 to 73.50 percent in 2017.

My recent ethnographic research among poor families in eastern Indonesia finds that the relationship between the way ECE has been expanded and its power to reduce future economic inequality is unfortunately not a straightforward journey.

Instead, it reveals some paradoxes. In many regions, poverty is usually concentrated in particular areas, consequently, many ECE centers are run by no one but the community members themselves.

Along the way, the intention to make poor children flourish through preschool has contributed to the exploitation of poor families’ already overstretched resources and the perpetuation of women’s disadvantageous position as cheap labor.

Therefore, before joining the cheering crowd, we should shift away from statistics and macroeconomic pride, to first critically understand how the ECE project has operated, especially in poor communities. The following is a glimpse of a local story.

When Antonio, not his real name, heard about ECE for the first time in his hometown of Atambua, East Nusa Tenggara, he was fascinated with scientific explanations on young children’s rapid brain development.

As an eastern Indonesian, he was particularly excited about the promise of ECE as a powerful tool to tackle poverty. He always firmly believed that: “Eastern Indonesians are not poor people, we are just poor in terms of opportunities,” he said.

From that day on, he envisioned ECE as a critical stepping stone to break the intergenerational poverty trap that has haunted his home region for decades. Months later, Antonio decided to donate part of his land and his money to match the village-fund grants so an ECE center could be built for his village.

He recruited high-school graduates to teach, and worked with community health workers for routine health examinations and education.

Today, his school proudly caters to the children of 48 poor families, indicating the success of an early education development project.

Yet every day Antonio must think about how to feed his family, pay his own children’s school fees, and fund the center.

As the village largely relies on the informal economy, like other residents he does not have a stable job outside ECE; and never successfully collects monthly school fees of less than US$2 from the children’s parents.

In poverty-stricken areas like his hometown, many centers rely heavily on government funds or, if they are lucky, private donors, or whatever is available from their own income.

With his limited funds Antonio has also impoverished the teachers. He knows the money he pays them is insufficient. The teachers are all women from big families. Traditionally, their labor is needed at home and yet Antonio has managed to persuade them to stay by saying that teaching young children is the only respectable occupation for women, and teachers’ hard work will be rewarded in heaven.

Recently he has become increasingly anxious. He is now haunted by the government’s plan to reinforce the policy on teachers’ qualifications. “That [qualification] policy could crush centers like us overnight. None of us has the mandatory undergraduate degree. And if my teachers had one, how would I pay their salaries?” he asks.

Local elections complicate his situation. Instead of democratizing local development, his community has become so fragmented that nothing really occurs without suspicion and political consequences.

With his network, Antonio could have raised funds to help his teachers attain university degrees but he fears “unwritten” political consequences from potential donors.

His biggest fear is that the center will have to be closed, killing his dream of having the village children reach their full potential.

For some people, Antonio’s decision to open a center despite his own poverty might seem illogical. Yet, the power of discourse and the history of Indonesia’s development trajectory has been remarkably strong.

Development emits nuances of modernity, positivity and progressiveness, not to mention the magnet of “education” is often depicted as a tool to reach our dreams or to advance a nation. Reject either and we would be labeled as backward, conservative and irresponsible.

This current ECE expansion phenomenon also reverberates the critique of Xavier Bonal, a Spanish education professor, on the inverse relationship between education and poverty: If education is massively used to create a more equitable society, the same intensity should be deployed to address the impact of poverty on education.

In short, education is also a sector that struggles from the impact of poverty. Investing in ECE alone will never bear fruit without comprehensively tackling today’s many dimensions of poverty.

So, what does fighting inequality ethically mean when instead of easing inequality, we actually have added to the burden on poor people? We must be critically aware that campaigns to scale up and maintain ECE achievements also require sensitivity to poor people’s needs because they are not merely a means to an end.

***

The writer is a doctoral student from the Faculty of Education and Social Work, University of Auckland with the support of New Zealand ASEAN Scholars.