Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsVoice of solidarity rises from Depok campus: Better late than never

The lecturers’ defense of the student board was especially surprising, given that Indonesian academics rarely contribute to unresolved issues regarding Papua.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

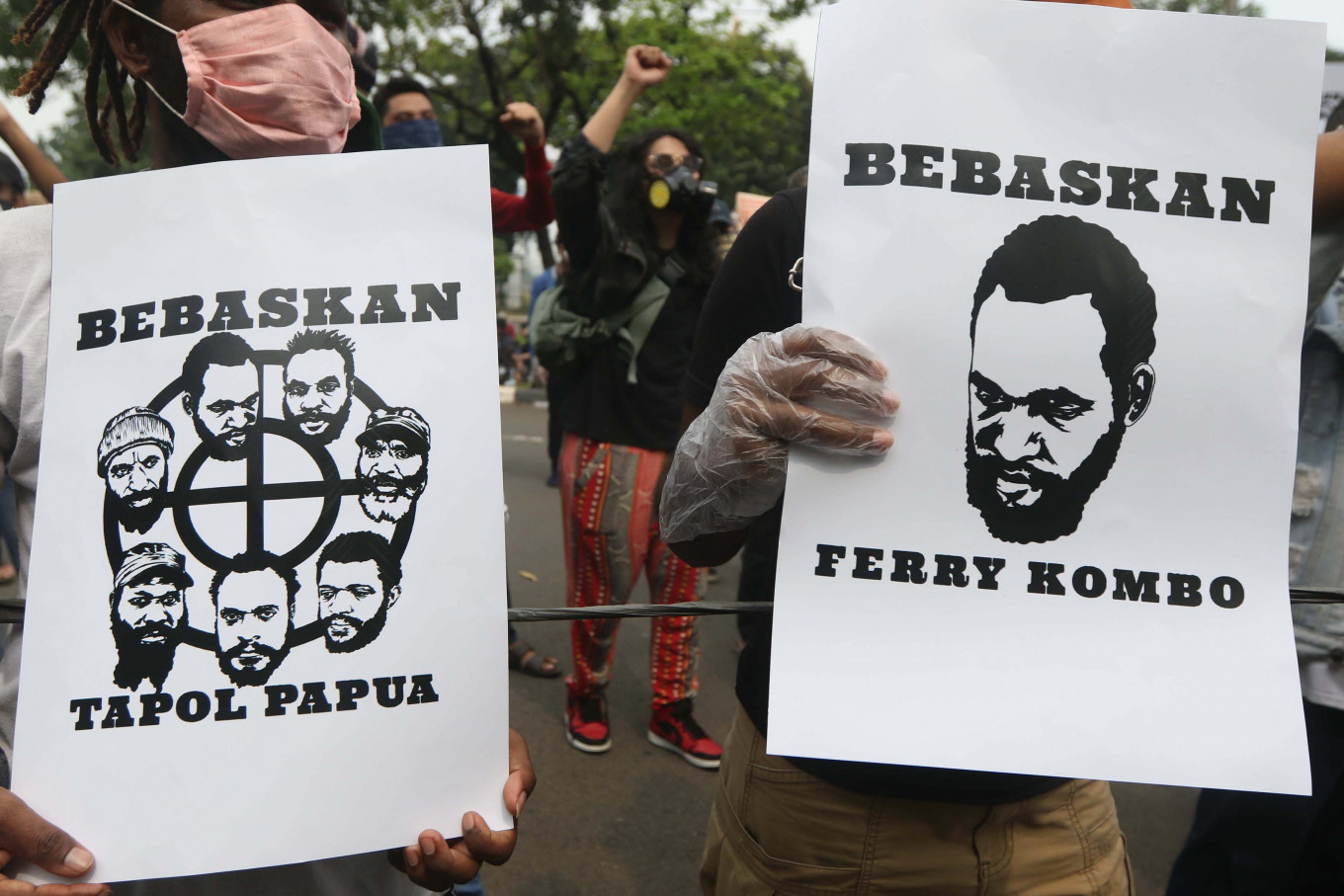

Protest for prisoners: Students and activists from the Papuan Political Prisoners Liberation Committee rally in front of the Supreme Court building in Central Jakarta on Monday, demanding that seven Papuans being tried at the Balikpapan District Court in East Kalimantan be cleared of all charges. (JP/Dhoni Setiawan)

Protest for prisoners: Students and activists from the Papuan Political Prisoners Liberation Committee rally in front of the Supreme Court building in Central Jakarta on Monday, demanding that seven Papuans being tried at the Balikpapan District Court in East Kalimantan be cleared of all charges. (JP/Dhoni Setiawan)

A

strange and solid voice emanated recently from the University of Indonesia (UI). After praising the student executive body (BEM-UI) for fostering free speech in its discussion on the sensitive subject of Papua, UI lecturers last week urged the university “to assume a more active role in disseminating diverse ideas [...] to avoid producing a [singular] truth”.

Come again?

The lecturers’ defense was unexpected, not only for my alma mater but for Indonesian academia. We expect silence from our lecturers, who have been wary of their job security and careers since the New Order, even after 22 years of Reformasi. Many academics don’t really care to seek what are likely to be uncomfortable truths beyond the one version we grew up with regarding Papua and other touchy issues.

Over 20 members of the UI Lecturers Alliance signed the above statement, which was issued in response to the rectorate’s criticism of the BEM-UI, that the June 6 talk lacked a “strong enough scientific foundation” and had invited “inappropriate speakers” (the discussion’s speakers included Veronica Koman, a renowned human rights activist and lawyer who has represented many Papuans, and Papuan activist Sayang Mandabayan).

Alliance member Shofwan Al-Banna told The Jakarta Post, “[...] we felt that it was crucial for us [to speak up] now, because the very essence of any university is to enable the search for scientific truths”.

We tend to romanticize the role of academics who, like journalists, are often challenged on their integrity. Yet if academics remain in their cocoons, they risk simply passing on many dominant, but not necessarily true, versions of Indonesia’s history.

The New Order survived as long as it did partly thanks to academics’ support for and the media’s reproduction of its “official truths”. Those lecturers who didn’t fit the confines of state universities sought positions at private Indonesian universities or went overseas, if they did not switch professions.

Leaving was better than enduring ostracization, the threat of dismissal or a stifling daily environment, some lecturers said. Thus, while state universities still struggle to reach even the top 100 in regional collegiate rankings, becoming a lecturer lack appeal.

The prevailing “truth” that relatively few Indonesian academics challenge include the “’65” – the mother of all taboo subjects referring to the failed 1965 coup, the subsequent witch hunt and massacres – and Papua’s unquestionable place in the Unitary Republic despite the Papuan people’s racial grievance.

Like other recent talks, the BEM-UI discussion on Papua and racism was prompted by the killing of African-American George Floyd by a white policeman in Minneapolis. The lecturers’ defense of the student board was especially surprising, given that Indonesian academics rarely contribute to unresolved issues regarding Papua.

Among their few contributions is the recently updated Papua Road Map by researchers of the Indonesian Institute of Sciences, which include their recommendations on addressing the fundamental problems of racism and the contrasting historical “truths” of how Papua became part of Indonesia.

Further, the chauvinism prevalent in higher education has led to institutional suppression of reports on sexual harassment and rape that involve respected male lecturers, while institutional conservatism has silenced gender minorities and efforts to promote interfaith tolerance.

Lecturers are not known for defending the outspoken student press, as in the case of Balairung Press at Gadjah Mada University (UGM). In 2018, Balairung published the results of its investigation into a female student’s allegations of sexual assault against another student, only to face denial, if not a cover-up, from UGM higher-ups.

Therefore, the lecturers’ support for a safe space to speak up comes better late than never, even as their integrity as scholars and educators continue to be challenged.

In 2016 for instance, UI lecturers joined in the fearmongering over the “spread of LGBT” that led to the closure of the Support Group and Resource Center on Sexuality Studies, which offered counseling for the university’s LGBT students.

In 2015, lecturer Rosnida Sari of Banda Aceh’s Ar-Raniry State Islamic University was suspended after publishing her experience in teaching students about interfaith tolerance, which included a dialogue with a local church minister. Her suspension, followed by public bullying, reflected the rising trend in intolerance, especially in the sharia-rule province.

Herlambang Wiratman, the president of the Indonesian Academic Freedom Caucus, said that academic freedom was no better today than it was under Soeharto, citing the new Science Law that requires permits for research on subjects deemed a threat to “national security” and “social harmony”.

Some academic discussions on controversial topics do reflect some progress, but their organizers must constantly take heed of the “who’s who” in the administration and their stance on non-mainstream views.

This means that all efforts to facilitate freedom count; although it would not restore what historians call the “lost generation” of Indonesia intellectuals.

Lecturers and students in 1960s Indonesia were targeted in the witch hunt against suspected communists led by university administrators and lecturers, as testified in 2015 at the International People’s Tribunal on 1965 Crimes Against Humanity in the Hague. This academic generation included thousands of exceptional students, the majority of whom never returned from their foreign scholarships in various countries, because the state revoked their passports and left them stateless.

The efforts of the UI Lecturers Alliance and others before them must grow and strengthen, as the hard-won freedom to speak one’s mind must never be taken for granted.

***

Staff writer at The Jakarta Post