Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPandemic showcases Indonesia’s systemic gender inequality

It is a rarity to find a conference or seminar in Indonesia with an equal number of men and women.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

T

he COVID-19 pandemic has required almost all events to go virtual, including in Indonesia. Information about conferences and seminars has been disseminated through digital posters containing the speakers’ photographs.

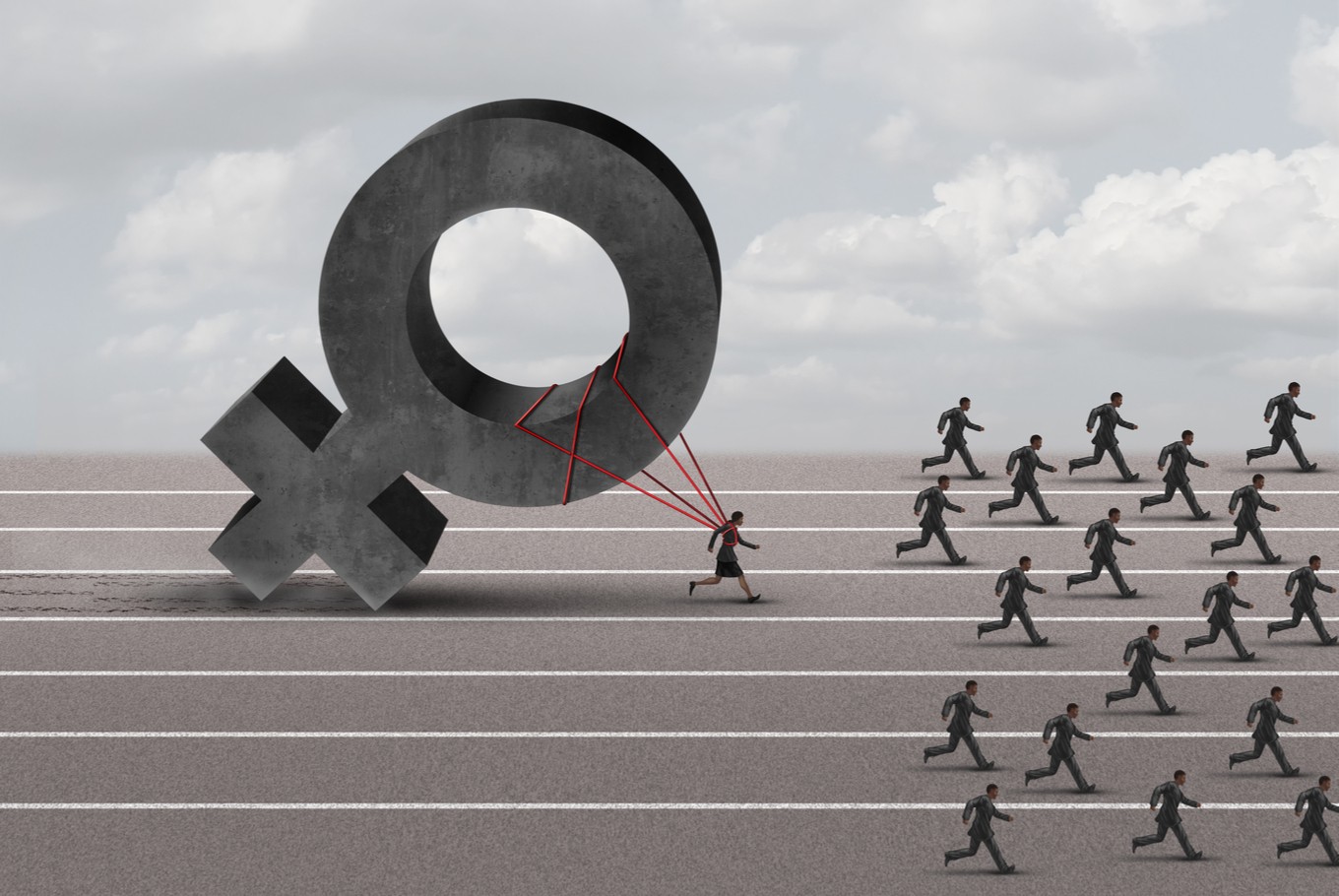

One cannot close one’s eyes to the male favoritism in Indonesia’s institutions. It is a rarity to find a conference or seminar in Indonesia with an equal number of men and women. Most strikingly, even those that do include women put them into gender-dictated roles, such as a chairperson.

Why is this the case?

Indonesia may have fewer problems than other countries with equal pay between genders, but the problem we currently have is no less systemic than the wage issue. Women need to receive the same acknowledgement for their leadership capacity and their understanding of issues within their field.

Some might argue that speakers are selected based on their knowledge – that these men are the brightest individuals in their respective fields. However, we must realize that in cases of high-level conversations, the speakers are almost always leaders in their institutions. So, it is not merely a “who to invite” issue; it is a leadership issue – something that is entrenched in our institutions.

Systemic gender inequality requires the attention of everyone – both men and women, regardless of their occupations or backgrounds. The argument that the central government and regional administrations have adopted the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which aim to achieve gender equality and women’s empowerment, might counter this critique by maintaining that we are actually progressing toward reducing gender inequality.

But how can one claim that progress has been made when male favoritism in leadership, as the most critical and systemic gender issue, has not been addressed?

In promoting women in leadership, developing countries mainly appreciate empowerment in terms of their ability to run their own small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). That matters.

However, gender inequality also persists in the formal sector – a sector that upholds the highest standards of giving decent wages and protections to its workers but does not actually have a clear vision when it comes to gender inequality in leadership.

In 1999, Amartya Sen wrote about “missing women”. Healthcare neglect caused 100 million women to die at birth or shortly thereafter. But newer findings have contributed to this debate and have concluded that the women were missing not simply because of health care. Building upon Sen’s work, Elisabeth Croll (2010) showed that cultural and economic factors contributed to female mortality. The missing women epitomize the inequality of opportunity between women and men and the reality of male favoritism. One might wonder what the cost of neglecting of women’s leadership will be. What will be the cost of stopping women from speaking their minds?

Sylvia Chant (2012) wrote that the current pursuit of gender equality through SME development might very well be the way to achieve “development on the cheap”. In a way, it is true. The linkage between women and development is always made through the growth narrative – that giving more opportunities to women in the labor force can elevate economic growth. The refusal to look at systemic gender inequality will not do justice to women.

Therefore, organizations that promote women’s empowerment and unions that seek to bring more women into the economy need to think about securing women’s rights in leadership as well. There is no written statement that women are forbidden to hold top leadership positions, but because there is no acknowledgement of male favoritism in leadership, everybody just treats the current leadership practice as normal. Therefore, women are unable to exercise their rights.

It is vital that policymakers use the pandemic as a time to reflect and change of the patriarchal nature of Indonesia’s leadership. Why do men dominate top-level positions, while women are merely deemed eligible for supporting roles, such as secretary or treasurer? Much like household patriarchy, in the existing leadership practices, women are mainly considered helpers instead of leaders.

Both the central government and local administrations need to open their eyes and establish a set of goals for promoting women’s leadership in the workplace. Both men and women have important things to say, and by putting on a blindfold regarding this matter, we allow the perpetration of gender inequality, which can produce unintended consequences.

But as much as it is the responsibility of policymakers, it is also our duty – that of individuals, men or women – to make a difference, wherever we dedicate our time and knowledge. If each of us passes on the acknowledgement of gender inequality in leadership to our friends, families and colleagues, a revolution will come.

The writer is a doctoral student at the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE)