Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsTranscending light: Expanding cultural reach of ‘Damar Kurung’ lanterns

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

Evoking Masmundar: Novan Effendy poses with his installation at the Biennale Jogja XVI, held in October 2021 in Yogyakarta. The piece was a tribute to the late Damara Kurung master artisan, Sriwati Masmundar, and reproduced her bedroom. (Courtesy Damar Kurung Institute) (Courtesy Damar Kurung Institute/Courtesy Damar Kurung Institute)

Evoking Masmundar: Novan Effendy poses with his installation at the Biennale Jogja XVI, held in October 2021 in Yogyakarta. The piece was a tribute to the late Damara Kurung master artisan, Sriwati Masmundar, and reproduced her bedroom. (Courtesy Damar Kurung Institute) (Courtesy Damar Kurung Institute/Courtesy Damar Kurung Institute)

L

ight art and interdisciplinary artist Novan Effendy talks about his approach to preserving Damar Kurung lanterns and expanding the meaning of the cultural object native to Gresik, East Java.

Nearing the opening date of the Biennale Jogja XVI in October 2021, interdisciplinary artist Novan Effendy was making finishing touches to his commissioned piece, Masmundari Memoria (2021) in one hall of the Jogja National Museum in Yogyakarta: a steel-framed canopy bed, complete with a set of curtains with embroidered flowers, placed in the middle of the 9-by-14-meter room with black walls.

A number of electrical Damar Kurung, a type of lantern native to Gresik, East Java, were suspended around the room, while some that looked unfinished were placed atop and around the bed. Effendy was puzzled when one of the lights pointed at the bed suddenly stopped working.

“It was working before. All the lights use the same extension,” Effendy told The Jakarta Post on July 4 at Rakarsa Haus in Cibeunying, Bandung.

Unmet maestro

His installation, commissioned by the Damar Kurung Institute for the Biennale Jogja XVI, was one of the last pieces to be finished. On opening day, Effendy placed the work’s pièce de résistance: a penginang, a box containing betel leaves, areca nuts, tobacco and betel lime for chewing, and a glass of black coffee on a woven mat in front of the bed.

The penginang and the coffee evoked the presence of late maestro Sriwati Masmundari who died on Dec. 25, 2005, a humble yet complex figure in the Indonesian art world who was said to be the last remaining Damar Kurung artist of her era.

Bright celebration: Novan Effendy (center rear, in black top) and the residents of Cibogo, Sukawarna village, Bandung, gesture during the Sariak Layung Damar Kurung parade on April 6, 2022 to mark the start of Ramadan. (Courtesy Rakarsa Foundation) (Courtesy Rakarsa Foundation/Courtesy Rakarsa Foundation)Propelled into prominence in 1987 through her debut solo exhibition at Bentara Budaya Jakarta, Masmundari was known for her habit of chewing betel leaves as she worked on her lanterns, sometimes late into the night.

“[It’s] A habit usually [common] among descendants of the Majapahit kingdom,” Effendy noted.

Damar Kurung, a box-shaped lantern with illustrations and ornamentation resembling an “M'' on each side, are usually sold ahead of Ramadan in Gresik, Effendy’s hometown. Its origins can be traced as far back as the Majapahit era.

“The initial concept was that we wanted to build a narrative about a museum, Masmundari’s museum. But we didn’t want our approach to be trapped in the current museum [concept], which seems to be a place to gather artifacts that are products of colonialism,” said Effency.

“We decided on [reproducing] one of the rooms in her house that could represent her work process, where the ideas for the stories depicted in Damar Kurung were born.”

None of Masmundari’s original works, however, were part of the exhibition. Effendy used replicas of Masmundari’s Damar Kurung.

“Our concept is not to show the artwork as the main exhibition [piece]. That’s not where artistic needs lie,” he explained.

“What we wanted is for the knowledge to be transferred to the current generation, regardless of whether it inspired them in their works or not,” Effendy said, emphasizing that “women from today’s generation” must continue the craft.

Guided by light

Effendy, who identifies as an artist of budaya cahaya, or literally “light culture”, founded the Damar Kurung Institute in 2016, five years after he organized the first Damar Kurung Festival in 2012. The nonprofit institute was established to support the development of Damar Kurung, archiving data and providing resources and knowledge to anyone interested in researching the craft in exchange for a copy of their research paper.

The schemed allowed maintaining a clear record as regards the outputs and inputs. “From only three research titles, now there are 65,” Effendy said.

The development of Damar Kurung then started to diverge, “no longer constrained to the field of esthetics”. The decision to incorporate references to Masmundari in the biennale, according to Effendy, was also partly due to the comprehensive data on the master artisan held in the institute’s archives.

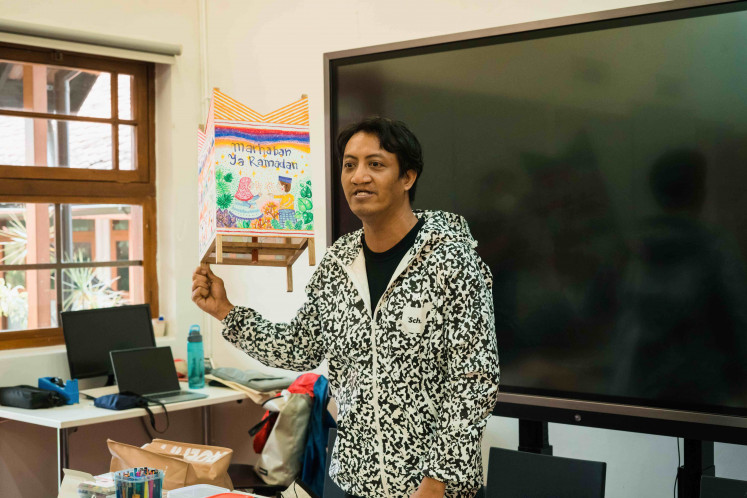

Inspiring light: Novan Effendy presents a Damar Kurung made by a resident of Cibogo, Sukawarna village, Bandung, during a workshop at the Goethe-Institut Bandung. (Courtesy of Rakarsa Foundation) (Courtesy of Rakarsa Foundation/Courtesy of Rakarsa Foundation)One of the key achievements of the festival Effendy initiated was lobbying the government to declare Damar Kurung as one of Indonesia’s intangible cultural heritage in 2017. Ultimately, the success of his effort widened Damar Kurung beyond a cultural object and shifted the perception of its “ownership” from Masmundari to the general public.

Effendy’s understanding transcends the confines of “Damar Kurung as Masmundari’s works”. What he sees is a much, much larger picture.

“When the term budaya cahaya is not used, there are two separate contexts involved: Tradisi lentera [lantern tradition] and budaya api [fire culture],” he said.

“They are two different things, actually, because lanterns nowadays use electricity, while back in the old days, they used fire. If we stretch back [further], not only fire, but even sunlight and moonlight can also be included in the context and that, I think, is something that is very primordial,” he continued. “The discovery of fire is quite complex in itself.”

In 2020, Effendy started independent research to map the traditions and cultures related to light and fire.

“I’m still working on it. It’s already there in terms of inventory and mapping,” he said, and all that was left was to produce a book.

Effendy also contributed an essay titled “Reconnecting the Lights of Southeast Asia” to an early 2022 edition of Down South, Outgazing Our Views by Further Reading Press, in which he discusses the use of light in a wider geographic context.

On dreams

His artistic brush with other “light cultures” in Southeast Asia came in parallel to the Biennale Jogja XVI. Effendy’s 2021 concept, A Home, was accepted and built on by the organizers of the Loei Art Fes 2021, held in Thailand’s Loei province. He noted that the province’s inherent values were taken into consideration, particularly its relationship with the concept of dreams.

According to Effendy, the belief of local farming families essentially prohibited youths from dreaming or having ambitions through a projected, established role as the families’ successors.

The final body of work was titled The Butterfly of Dreams and involved a series of hybrid workshops, including meditative theater. During the theater workshop, the members of the Mangkabia youth collective, named after the word for “butterfly” in the local dialect of Dan Sai district, western Loei, were asked to translate their dreams and ambitions through physical movements inspired by Damar Kurung illustrations.

Another involved making sculptures resembling butterflies, on which were hung pieces of bamboo with the participants’ dreams written on them, inspired by the illustrated frames of Damar Kurung. The sculptures were then placed in front of the maternity ward at Dansai Crown Prince Hospital.

“The hospital was fully on board,” Effendy said with a smile, noting that the sculptures’ placement lent them complexity. He said the concept was particularly inspired by his collaboration with Hong Kong artist Kingsley Ng at Surabaya Zoo in 2015.

“The concept of the work was how a traditional zoo transitions toward a conservative society, that a zoo is essentially a conservation [space] for endangered animals, not a community for animals.”

That piece also involved children, asking them to imagine the future of the animals living in the zoo. This was then translated into silhouettes installed on lanterns as well as stories that were performed in the evening.

It was then that Effendy realized that his artwork was more inclined toward activism.

“I think that it is time for us, if we want to revive Damar Kurung, to not [stay] trapped in its creeds or accidentally repeat history.”

Effendy is currently trying to encourage cultural discourse by introducing Damar Kurung in West Java through a pilot project in Cibogo, Sukawarna village, Bandung, during his fellowship with Goethe-Institut.