Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsOn the road with José Ramos-Horta

But that’s Ramos-Horta. He is neither Che Guevara nor Sukarno. He is a realistic man and leader who has experienced, endured and overcome many things – from gun battles in East Timor’s forests to negotiation wars against colonial powers to free his country, and from handling the delicate separation process with Indonesia to the nation building and development of his country.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

“Have you ever imagined, if only Indonesia didn’t invade Timor Leste in 1975, would everything be very different now? Would your country be much better than it is today?” I asked José Ramos-Horta during a road trip from Dili to Baucau, the country’s second largest town, earlier this month.

He drove his glamorous antique beach buggy, while I sat next to him. A car driven by his security guards followed behind us.

“It’s difficult to answer that,” he said. “Indonesia did many good things, especially in education.”

I didn’t expect that kind of answer to an almost rhetorical question, especially from Timor Leste’s founding father. I have always imagined that if Indonesia had not invaded Timor Leste – then known as East Timor – in 1975, the country would have been more prosperous. The small region connected by land to Indonesia’s West Timor would have been an independent nation for more than 40 years by now. With a longer period of nation building, I believed, Timor Leste would not have been one of the youngest and poorest countries in the world.

Moreover, I was talking to a man who has dedicated almost all of his life to fighting for the freedom of the country. I expected a more revolutionary and romantic answer. Something that made me feel bad as an Indonesian, but at the same time made me keen to talk about fighting for freedom, and struggling against colonialism, postcolonialism and so on.

But that’s Ramos-Horta. He is neither Che Guevara nor Sukarno. He is a realistic man and leader who has experienced, endured and overcome many things – from gun battles in East Timor’s forests to negotiation wars against colonial powers to free his country, and from handling the delicate separation process with Indonesia to the nation building and development of his country.

He was an exile, a Nobel prize laureate, a president, and now he is a leader who is finding ways to fulfill what the people of his country really need.

(Read also: Timor Leste looks to benefit from ASEAN membership)

José Ramos-Horta was an exile, a Nobel prize laureate, a president, and now he is a leader who is finding ways to fulfill what the people of his country really need. (*/Okky Madasari)

José Ramos-Horta was an exile, a Nobel prize laureate, a president, and now he is a leader who is finding ways to fulfill what the people of his country really need. (*/Okky Madasari)

Driving from the country’s capital to Baucau took me back to my childhood in an East Java village in the 1980s. Dusty roads, farmland, basic warung (food stalls). Old men, women and students were walking for long distances under the sun yet were happy and enthusiastic to see their president pass by. “Bom dia… bom dia!” People said as they greeted him and waved, meaning “good morning” in Portuguese.

Ramos-Horta happily waved back to all of them.

The trip also took me back to my childhood fairytale world. A story about a king riding his horse, greeted and waved at by his people along the road, in the middle a beautiful landscape: a cloudy blue sky, green paddy fields, hilly roads, mountains and beaches.

But no, it was not a fairytale. It was also not the 1980s.

Everything became very real when we stopped at a market, but not like the markets I was used to seeing. It was a row of stalls displaying fruits and vegetables. Ramos-Horta bought something from every stall: bananas, papaya, pumpkin, water spinach and cassava. The prices in the country, which uses US dollars as its currency, were higher than those in Indonesia. A big watermelon was $7, while in Jakarta we could buy the same watermelon for no more than $4. “People here still don’t know how to price products,” Ramos-Horta explained.

Still at the market, several women came up to me speaking Indonesian. They said Ramos-Horta always stopped by when visiting Baucau and talked to them. “He is the only leader who does that. I hope he will run again in the next election so I can vote for him,” said one woman. When I told Ramos-Horta what the woman said, he replied: “Terima kasih.”

Ramos-Horta doesn’t speak Indonesian. It is known as a working language in Timor Leste now, along with English. The country’s official languages are Tetun and Portuguese.

When we stopped at a warung, I could hear a television in a nearby house airing an Indonesian infotainment program. Indonesian TV channels are still a favorite for many Timorese people. They use parabolic antenna to get the channels. That’s why many kids who were born and grew up after 1999 can speak Indonesian even though schools don’t use it anymore. They learn the language from TV.

Returning to Dili after the trip made the capital seem like a real city, with its crowded roads, office buildings lining the main streets, various restaurants and stores — from Turkish and Indian restaurants to a shop with Indonesia’s “Sarimi” brand name on the roof and a Burger King. We also found a shopping center and a newly established cinema.

Yet everybody still greeted and waved at the former president and said “Bom dia” or “Boa tarde”.

(Read also: Indonesia, Timor Leste agree cooperation in human resource development)

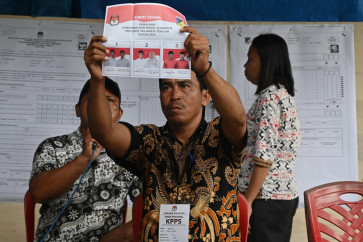

The prices in the country, which uses US dollars as its currency, were higher than those in Indonesia. (*/Okky Madasari)

The prices in the country, which uses US dollars as its currency, were higher than those in Indonesia. (*/Okky Madasari)

On one road in the city I saw a big banner announcing a Pride Parade, an event to celebrate and promote lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) rights in Timor Leste. I was surprised that the activity could be held openly in the country.

“Timorese don’t see LGBT people as a problem,” Ramos-Horta said when I asked him about the issue. “We don’t care about people’s private lives. Even in politics we never use religion, marriage, or sexual preferences as an issue.”

I laughed. Of course, I had compared the situation to Indonesia. What would happen if there was banner for a Pride Parade on a road in Jakarta? We laughed together, remembering a huge protest against the ASEAN Literary Festival in Jakarta that featured LGBT issues as a discussion topic. The festival in early May presented Ramos-Horta as the keynote speaker.

On my last day in Dili, I took a morning walk with Ramos-Horta from his house to Cristo Rei, a tall statue of Jesus that was built by Indonesia. We walked along the main road parallel to the beach. It was 7 a.m. or so, and many people were walking, running, or biking, and shouting “Bom Dia” as they passed by the former president.

At the time I could imagine what happened in 2008 when Ramos-Horta was shot by rebel soldiers. It took place in the morning, when he was taking a walk but decided to return home after hearing about gunshots at his house. He was then shot outside of his home.

The traumatic experience did not change Ramos-Horta at all. He has the same casual routine: a morning walk with one security officer, driving his car across the country, going to restaurants and watching the sun go down every evening.

(Read also: Reuniting Timor Leste children stolen by Indonesia)

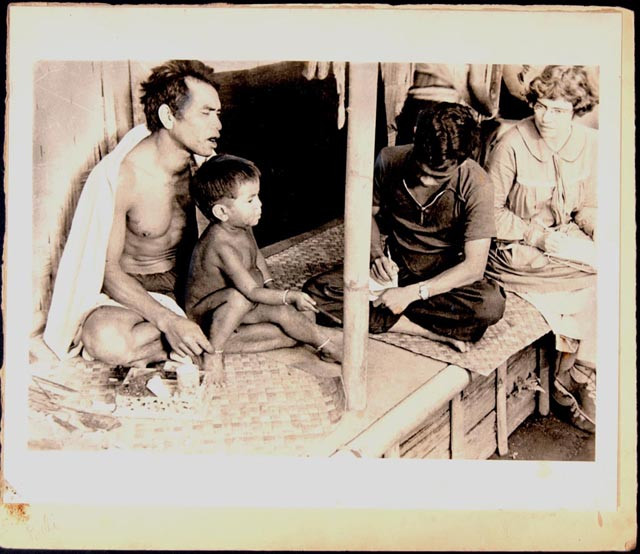

Old men, women and students were walking for long distances under the sun yet were happy and enthusiastic to see their president pass by. “Bom dia… bom dia!”(*/Okky Madasari)

Old men, women and students were walking for long distances under the sun yet were happy and enthusiastic to see their president pass by. “Bom dia… bom dia!”(*/Okky Madasari)

We enjoyed the last sunset of my visit in Timor Leste on the beach in front of the government building, near the Santa Cruz Massacre Monument, which depicts statues commemorating the 1991 shootings by the Indonesian Army that killed at least 250 Timorese.

The mass shooting was a key turning point in Timor Leste’s struggle toward independence as the incident raised awareness of the Indonesian invasion and brutality around the world and also within Indonesia itself.

During the morning walk, we by chance met and talked with one of the men depicted in the monument. He is now the only living survivor of the massacre.

I could not resist asking Ramos-Horta the most haunting question about Timor Leste and Indonesia’s relationship, on the possibility of an international war crimes tribunal, and efforts to open cases of gross human rights violations.

But Ramos-Horta said firmly: “We don’t need that. Many Timorese joined the pro-Indonesian integration movement and Indonesian Army at the time. Should we bring all of them to the tribunal?”

As the sun went down, I realized that I had fallen in love with the young country, inspired by its great man.

***

Okky Madasari is an Indonesian novelist. Her novels are Entrok (The Years of the Voiceless), 86, Maryam (The Outcast), Pasung Jiwa (Bound) and Kerumunan Terakhir (The Last Crowd). She is the cofounder of the ASEAN Literary Festival.

---------------

Interested to write for thejakartapost.com? We are looking for information and opinions from experts in a variety of fields or others with appropriate writing skills. The content must be original on the following topics: lifestyle ( beauty, fashion, food ), entertainment, science & technology, health, parenting, social media, travel, and sports. Send your piece to community@jakpost.com.