Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsJokowi’s foreign policy comes late, but internationally impactful

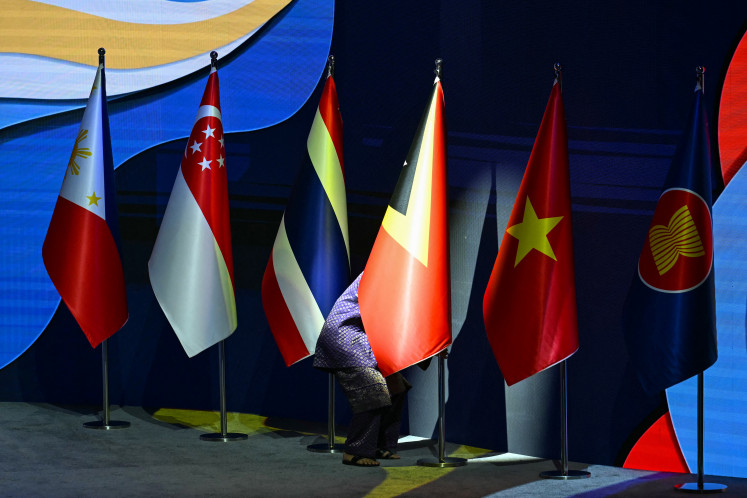

Indonesia’s turns at the presidency of the Group of 20 this year and ASEAN chairmanship next year have forced Jokowi to devote much of his time and energy to foreign affairs.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

When ending his second five-year term in October 2024, President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo will likely be remembered as a president who only got serious about foreign affairs in the last three years of his tenure. It is not because of his ambition to appear on the world stage, but because of the leadership role he has had to play in two global-level organizations.

So what kind of legacy will he leave?

Compared to his predecessors, President Jokowi is a latecomer in the foreign-policy arena and prefers to entrust Foreign Minister Retno Marsudi to deal with the matter on a daily basis. The most extreme example is his refusal to attend the United Nations General Assembly sessions since he came to power in October 2014. He addressed the annual event just once -- but virtually -- last year.

Unlike former president Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, who loved to see Indonesia gain prominence in global politics, Jokowi is very pragmatic and inward-looking. His background as a former entrepreneur has taught him to pay attention to cash flow and short and medium-term gains.

His inward-looking tendency and his “overemphasis” on national economic interests are among the reasons for his comparative lack of desire to engage in foreign affairs. But Indonesia’s turns at the presidency of the Group of 20 this year and the ASEAN chairmanship next year have forced him to devote much of his time and energy to foreign affairs.

Jokowi’s success in hosting the G20 Summit in Bali earlier this month has impressed the world, including western media. He proved the free and active foreign policy that has been the DNA of Indonesia. Jokowi, for example, refused to expel Russia from the elite group or disinvite Russian President Vladimir Putin from the Bali summit despite strong pressure from Western leaders, who want to punish Russia for invading Ukraine.

The free and active foreign policy was coined in the wake of a rivalry between the Western and Eastern blocs. In line with the doctrine, Indonesia cofounded the Non-Alignment Movement (NAM) and hosted the NAM summit in Jakarta in 1992.

History saw Indonesia practically lean to the East during the era of Sukarno, and after the regime change in 1966 the country shifted to the West.

Jokowi lacks interest in regaining Indonesia’s role in NAM, South-South cooperation and other developing countries' movements that promise more international prestige than concrete economic benefits. He is not keen to broker peace, although he did quite an intensive diplomatic stunt in Palestine and Afghanistan in order to keep the trust of his domestic audience.

For Jokowi, diplomacy serves the economy -- investment and trade, on top of protection of citizens abroad. He has repeatedly told Indonesian ambassadors to bring more foreign investment into the country. His approach in diplomacy is very realistic.

In his first five-year term, Jokowi emphasized infrastructure development, which is why he came to China, which provided what Indonesia wanted with no strings attached. Jokowi believed China’s business-to-business scheme to be more attractive than Japan’s government-to-government model.

That is why Jokowi dropped the nearly completed negotiation on the Jakarta-Bandung high-speed train between Japan and Indonesia when he visited China in October 2014. Jokowi made it very clear that his business orientation was China, which is unfortunately at the expense of decades-long ties with Japan.

Jokowi awarded the Jakarta-Bandung train project to China, using an “excuse” that China offered a “business-to-business” financing scheme while Japan rigidly demanded the “G-to-G” format.

But like most of his predecessors, minus Sukarno, de facto, Jokowi is also pro-West in terms of regional security and international politics. He wants the strong presence of the United States military as well the Quad security cooperation involving the US, India, Australia and Japan. Quietly, Jokowi does not mind the military pact linking Washington DC, Canberra and London.

Traditionally, Indonesia tends to be hostile to China both politically and militarily, as proven by the freezing of diplomatic relations for 25 years until 1990. Indonesia is not a claimant of the South China Sea. China also insisted on the Natuna waters as its fishermen’s traditional fishing destination for centuries. But Indonesia will not make any compromise on the waters, which belong to Indonesia’s Exclusive Economic Zone as recognized by the 1982 United Nations Convention of the Law of the Sea.

Various international organizations from time to time predicted that Indonesia’s economic power will likely jump to a much higher position in the next two decades, which should influence major powers’ views about Indonesia under Jokowi’s administration.

In the beginning, there were anxieties, including from Japan, the US and also Australia, that Jokowi would be too close to China, Indonesia’s largest economic partner. But there are so many countries that are too dependent on China. Even members of the Group of 7 are not an exception.

But Jokowi’s hardening position on the issue of Natuna waters became clear, and louder than ever, after Indonesia’s G20 presidency. Major G20 countries are now convinced of Indonesia’s free and active foreign policy, and his firm persistence not to exclude Russia from the G20 is also another winning point.

But what are the achievements of Jokowi in foreign affairs?

First, Indonesia’s sovereignty and sovereign rights are not for negotiation, even with a close friend like China, when it comes to the Natuna waters. And China got the message.

But Indonesia cannot do much to help resolve the dispute over the South China Sea, which is mostly claimed by China. Indonesia’s clear position shows that the rules of the game cannot be dictated by China.

Second, Jokowi’s leading role in ASEAN’s concerted measures against Myanmar’s junta leader Gen. Min Aung Haling have been quite effective in reducing international pressure on ASEAN. Other fellow ASEAN leaders follow suit, and the interpretation of the non-interference principle as stated in the ASEAN Charter is becoming more flexible. There are high hopes for ASEAN’s democratization process, even if it proceeds at a snail’s pace.

Third, Indonesia’s successful hosting of the G20 Summit will be a precious working capital for it to play more international roles in the future.

Amid the geopolitical rivalries, Indonesia, however, will not act on a bilateral basis. It prefers to work with ASEAN as a group because it will be more effective. The regional bloc will try to show unity in many issues, although it will be uneasy because of their different geopolitical interests.

Indonesia will never align itself with any power, although it is often very hard to stand in the middle or neutral. But to take sides is never the choice for Indonesia, at least on the surface. There will be a point when Indonesia cannot stay neutral, as evident in the case of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Indonesia joined the world’s condemnation, although at the same time it refrained from boycotting Russia.

China is now the most-important trading and economic partner for Indonesia, and many other countries. On the other hand, Indonesia wants the US to maintain its military presence in the Asia-Pacific for the sake of regional stability.

President Jokowi still has two more years to write the history of Indonesian foreign policy. Maybe not very phenomenal, but quite substantial.

***

The writer is a senior editor at The Jakarta Post. This article is a full version of his presentation at the Conference on Indonesian Foreign Policy (CIFP) 2022 “Navigating a Turbulent Ocean” in Jakarta on Nov. 26.