Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsReaping Indonesia’s demographic dividend: A supply and demand view

According to Elsenhans and Babones, becoming a middle-income economy requires only moderate productivity and a moderately competent administration; conversely, becoming a high-income economy requires nothing short of high productivity, as well as strong and effective governance.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

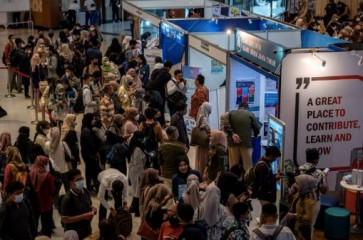

Crowds of job seekers throng a job fair on March 7, 2023, in Surabaya, East Java. Data from Statistics Indonesia show that open unemployment in the country was 4.82 percent of the 149.38 million-strong workforce in February 2024, down 0.63 percent compared to the same period last year. (Antara/Juni Kriswanto)

Crowds of job seekers throng a job fair on March 7, 2023, in Surabaya, East Java. Data from Statistics Indonesia show that open unemployment in the country was 4.82 percent of the 149.38 million-strong workforce in February 2024, down 0.63 percent compared to the same period last year. (Antara/Juni Kriswanto)

I

n their seminal book, BRICS or Bust?, Hartmut Elsenhans and Salvatore Babones set out the proposition that middle-income economies often become ensnared in what is known as the middle-income trap. The result is that while it is relatively easy for poor economies to develop into middle-income economies, it is notoriously difficult for middle-income economies to become high-income economies. Indeed, the empirical evidence is clear: Few economies across the globe have been able to make the successful leap from middle-income to high-income in recent decades, with Singapore being a notable exception.

This has important implications for Indonesia. Having survived tribulations such as the 1998 Asian financial crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic in our economic development journey, Indonesia is now on solid footing as a middle-income economy. But what is now confronting us may just be our greatest challenge yet.

According to Elsenhans and Babones, becoming a middle-income economy requires only moderate productivity and a moderately competent administration; conversely, becoming a high-income economy requires nothing short of high productivity, as well as strong and effective governance. Failure to achieve excellence in either or both dimensions invariably results in the middle-income trap. Capitalizing on Indonesia’s demographic dividend As Indonesia prepares to surmount this middle-income trap over the next few decades, it has one unique advantage working in its favor: a sizeable demographic dividend, which is expected to peak in the 2030s with 68 percent of Indonesians at their productive working age.

In a speech delivered by outgoing President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo in 2023 during the unveiling of the final phase of the 2025-2045 National Long-Term Development Plan (RPJPN), he spoke of how the plan intends to ride on this demographic dividend to propel economic growth toward a per capita income of US$30,000 — at which point Indonesia would be considered a high-income economy under the Golden Indonesia 2045 vision.

The President, however, did point out a crucial caveat: Indonesia’s demographic dividend is a “crisitunity”, a double-edged sword that could be an opportunity or a disaster depending on how it is wielded. What ensued shortly thereafter was a national debate on the Job Creation Law and its adequacy to support the nation’s lofty Golden Indonesia 2045 ambitions.

Enacted on Nov. 2, 2020, amid much anticipation, the law had sought to create a more business-friendly environment by simplifying business licensing processes and providing financing, resources and incentives to businesses, especially those considered to be micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs).

As its name suggests, a significant part of this law also entails reforming labor regulations to make it easier for businesses to hire and manage employees, and thereby enhance Indonesia’s overall workforce participation. Among concerns raised by labor unions, environmental groups and other civic organizations were the effectiveness of the law in actual job creation, particularly within the context of Indonesia’s post-pandemic recovery, as well as social and environmental concerns, such as workers’ rights, job security and sustainability practices.