Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsRegional elections and the struggle for inclusive citizenship

Structural deprivation, including insecure land tenure, inadequate access to clean water and persistent inequalities, denies the urban poor the ability to exercise citizenship fully.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

“Citizenship is a status bestowed on those who are full members of a community […] It implies the enjoyment of a full range of civil, political, and social rights,” said TH Marshall in his seminal work Citizenship and Social Class. Marshall envisioned citizenship as more than a legal status. It encompasses access to fundamental rights and services that uphold dignity and equality. Yet in Jakarta, as in many major cities in Indonesia, this vision remains far from reality. Structural deprivation, including insecure land tenure, inadequate access to clean water and persistent inequalities, deny the urban poor the ability to exercise citizenship fully.

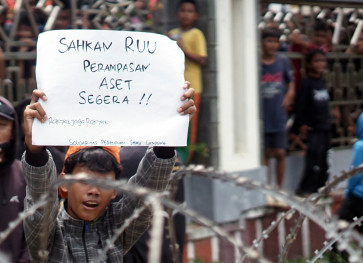

Direct regional elections are often framed as milestones of democratic progress, offering the promise of greater civic engagement. However, for Jakarta’s marginalized communities, these processes often hold little significance when basic needs remain unmet. My ongoing research into Jakarta’s urban poor highlights that struggles over housing rights and basic services are central to their experience of citizenship. These systemic issues reflect a harsh reality: Citizenship in practice often falls far short of the ideal. Without addressing these inequities, the promise of citizenship remains an empty aspiration for the city’s most vulnerable residents.

Marshall’s theory of citizenship emphasizes a balance between three key elements: social, civil, and political rights. Social rights include access to economic welfare, housing and essential services that enable individuals to live with dignity. Civil rights encompass personal freedoms, such as property ownership, freedom of movement and legal protections. Political rights ensure the ability to vote and participate in governance. Marshall’s framework suggests that the erosion of any one of these components renders citizenship incomplete.

In Jakarta, this imbalance is starkly evident. Marginalized communities in kampungs, particularly in vulnerable coastal areas, lack access to the social rights essential to full citizenship. Promises to improve housing, clean water access and protection from environmental hazards like flooding are frequently made during election campaigns but are seldom fulfilled. Instead, these foundational rights are often reduced to political leverage, distributed or withheld based on electoral considerations. When basic services are treated as negotiable favors rather than guaranteed rights, citizenship becomes a transactional relationship, stripped of its deeper meaning.

This pattern is evident in every regional election, where candidates routinely pledge solutions to longstanding issues such as housing insecurity and inadequate water access. These promises, while temporarily inspiring hope, rarely translate into sustained improvements. Election after election, the same issues resurface, serving as convenient bargaining chips. For Jakarta’s marginalized communities, this cycle reveals a stark reality, the right to full citizenship remains out of reach, and electoral promises are little more than fleeting gestures of inclusion.

The consequences of this deprivation extend beyond unmet social needs, directly impacting political participation and engagement. Marginalized groups, forced to prioritize immediate survival, often lack the resources or capacity to participate meaningfully in elections. Weak land tenure security, poor housing conditions and inadequate education further limit political awareness, hindering individuals’ ability to make informed choices or advocate for systemic change.

Prolonged deprivation also erodes aspirations for meaningful leadership. Among Jakarta’s urban poor, this disillusionment is increasingly evident. The Jaringan Rakyat Miskin Kota (JRMK), a prominent network advocating for these communities, has adopted the “vote for all” movement, a euphemism for abstention from voting. Conversations with residents in Muara Baru, a coastal kampung in North Jakarta, reveal uncertainty about whether to cast their votes or align with this movement. For many, this choice reflects not apathy but a deep critique of a system that consistently fails to deliver on its promises.