Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsWhy the House struggles to maintain independence and trust

Pent-up frustrations due to House’s failure to represent citizen interests erupted into large scale demonstrations.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

L

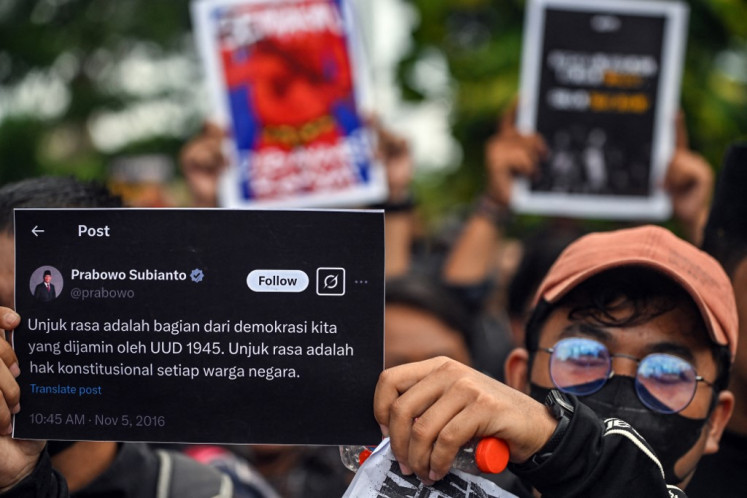

arge demonstrations hit Jakarta recently as angry protesters demanded the dissolution of the House of Representatives. Under the hashtag #BubarkanDPR (“dissolve the house”) frustration spilled onto the streets, fueled by discontent over the country’s economic direction and the perceived disconnect between lawmakers and ordinary citizens.

The spark was the revelation that each House member receives a monthly housing allowance of Rp 50 million (US$3,000), around 10 times Jakarta’s minimum wage and 20 times the minimum wage in poorer regions. On top of this, each member also receives Rp 4.2 billion annually in constituency expenses.

The anger deepened when one member reportedly dismissed critics as “dumb”, and another publicly complained about traffic jams on the way to the House building.

For citizens facing layoffs and higher taxes amid a government “efficiency” drive, the House seemed tone-deaf and out of touch.

But the problem runs deeper than high salaries or insensitive remarks. The crisis of legitimacy facing the Indonesian lawmakers reflects the slow erosion of the legislature’s independence and relevance within the country’s democracy.

When former president Soeharto fell in 1998, democratic reformers sought to build a strong legislature that could counterbalance presidential power. The constitutional amendments that followed introduced term limits, direct presidential elections and more robust checks and balances.

The president could no longer dissolve the legislature. Its agreement was required to pass laws and budgets, and it was tasked with overseeing the executive.

For a time, it lived up to that role. As one lawmaker told political scientist Patrick Ziegenhain in his 2008 book “The president has a lot of power, and it is our job to limit it”.

Between 1999 and 2014, House members frequently used their powers to scrutinize the government and speak on behalf of the public. But two institutional flaws weakened this democratic experiment.

First, reformers’ fears of continued dominance of Golkar, once Soeharto’s electoral vehicle, led them to adopt proportional representation. This produced a fragmented multi party system, and where no president has commanded a stable majority.

Second, the House retained the New Order’s consensus procedure. In the House commissions, faction leaders or members appointed by party bosses act as proxies for party elites. Real bargaining happens behind closed doors between party chairs and the president, leaving individual members with little voice.

The result is a legislature where members are more accountable to their party boards than to their voters. Meaningful policy debate is minimal, and members have little incentive to develop expertise in their committees.

As one member bluntly told a minister lobbying for a bill: “Please don’t lobby here, sir. We are all subordinates. Speak to the party chairmen first.”

One of the root causes of the legislature's institutional decline is that electoral campaign costs have spiraled beyond the reach of most citizens.

Unsurprisingly, nearly half of the members elected for the 2019–2024 period came from business backgrounds or had wealthy patrons. A study, for instance, found that on average, a legislative candidate might have spent millions of US dollars to get elected during the 2024 election.

This trend has further narrowed representation. Elected members are widely perceived as serving their financiers and party leaders rather than their constituents.

Once elected, members are reluctant to challenge the system. Having sunk fortunes into their campaigns, they need to stay on good terms with party elites to secure their political future.

In Indonesia’s fragmented multiparty system, where campaign costs are excessively high, access to ministries and state resources is critical for parties to sustain themselves, often resulting in an oversized coalition supporting the ruling party.

Between elections, political parties scramble for access to positions, ministries, legislature chairs, state-owned companies’ executives and government contracts. Government ministries also fund a variety of discretionary appointments that can be filled by party members.

Conversely, a party that becomes too critical risks losing access to patronage or face direct government intervention. As such, institutional incentives are heavily stacked in favor of political parties being within rather than without the system.

Since the start of Indonesia’s democratic era, every president had been a minority president, unable to secure a legislative majority through his own party, including Prabowo Subianto-led Gerindra Party.

In a fragmented multi-party system where the president’s party does not hold a majority, a powerful legislature can easily become obstructionist or disruptive.

Former president Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono lamented in his memoir that Indonesia had effectively become “semi-parliamentary or semi-presidential,” with parties in the House strong enough to block presidential agendas.

The response from successive presidents has been to co-opt the House by controlling political parties from within. Yudhoyono, for example, brought Golkar into his coalition by backing then-vice president Jusuf Kalla’s bid for party chairmanship.

His successor, Joko “Jokowi” Widodo, followed a similar playbook. Although he initially promised a “slim coalition”, he quickly expanded it after facing legislative resistance, even intervening directly in party leadership disputes to secure loyal chairs.

President Prabowo inherited Jokowi’s broad coalition and rewarded party leaders with key cabinet posts.

As a result, almost every major party in the House is now part of the ruling coalition. Lawmakers answer primarily to their party chairmen, who are themselves embedded in government, making the legislature a subordinate institution rather than an independent counterweight.

To maintain stability in a fragmented multiparty system, Indonesian presidents are compelled to build oversized coalitions, a safeguard in case one or more parties defect.

Presidential pressure, combined with the need to access state resources, makes parties reluctant to challenge the government.

In addition, the high cost of entry and House’s poor public image deters many capable Indonesians from running for office.

There is also little incentive for House members to develop strong capabilities in the policy area that they are overseeing. As a result, the House has become less representative and less capable over time.

This hollowing out of the legislature has left it neither independent from the executive branch nor accountable to voters.

The chants of “Bubarkan DPR” carry a truth reformers cannot ignore: Unless the legislature is reformed to restore its independence, transparency and representativeness, Indonesia’s democratic institutions will continue to decay.

---

The writer is a post-graduate student at Australian National University. The article was republished under a Creative Commons license.