Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsMore than 60 UN members sign cybercrime treaty opposed by rights groups

The new global legal framework aims to strengthen international cooperation to fight digital crimes, from child pornography to transnational cyberscams and money laundering.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

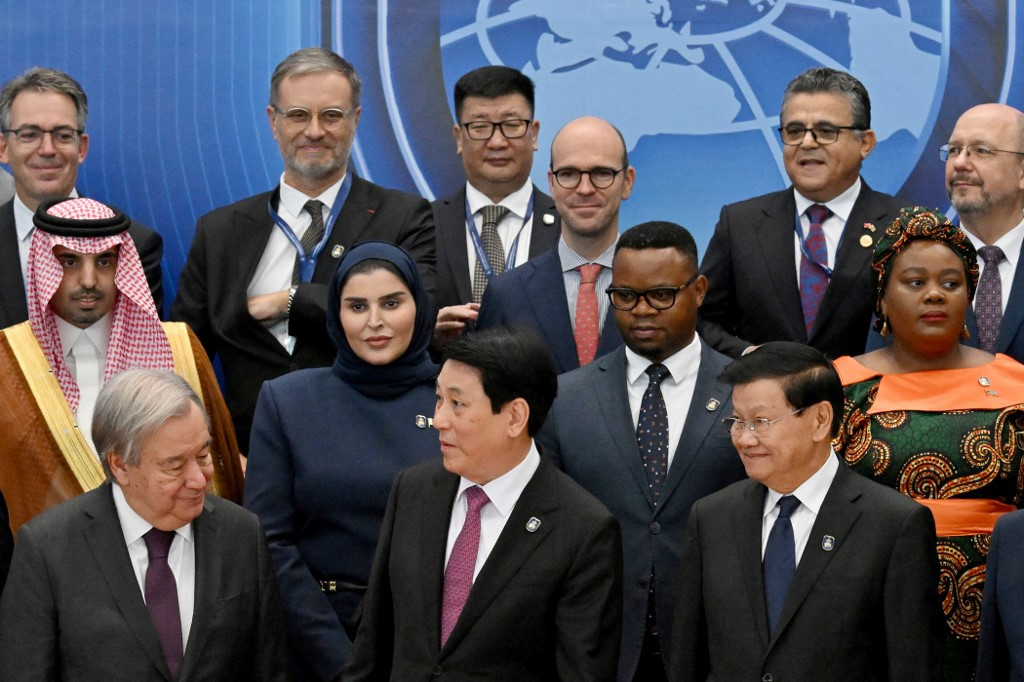

(Front, from left to right) United Nations secretary-general António Guterres, Vietnam's President Luong Cuong and Laos' General Secretary and President Thongloun Sisoulith pose with other leaders and delegates at the signing ceremony of the UN Convention on Cybercrime in Hanoi, Vietnam on Oct. 25, 2025. Countries signed their first UN treaty targeting cybercrime in Hanoi on Oct. 25, despite opposition from an unlikely band of tech companies and rights groups warning of expanded state surveillance. (AFP/Nhac Nguyen)

(Front, from left to right) United Nations secretary-general António Guterres, Vietnam's President Luong Cuong and Laos' General Secretary and President Thongloun Sisoulith pose with other leaders and delegates at the signing ceremony of the UN Convention on Cybercrime in Hanoi, Vietnam on Oct. 25, 2025. Countries signed their first UN treaty targeting cybercrime in Hanoi on Oct. 25, despite opposition from an unlikely band of tech companies and rights groups warning of expanded state surveillance. (AFP/Nhac Nguyen)

C

ountries signed their first United Nations treaty targeting cybercrime in Hanoi on Saturday, despite opposition from an unlikely band of tech companies and rights groups warning of expanded state surveillance.

The new global legal framework aims to strengthen international cooperation to fight digital crimes, from child pornography to transnational cyberscams and money laundering.

More than 60 countries were seen to sign the declaration Saturday, which means it will go into force once ratified by those states.

UN secretary-general Antonio Guterres described the signing as an "important milestone", but that it was "only the beginning".

"Every day, sophisticated scams, destroy families, steal migrants and drain billions of dollars from our economy," he said at the opening ceremony in the Vietnamese capital on Saturday. "We need a strong, connected global response."

The UN Convention against Cybercrime was first proposed by Russian diplomats in 2017, and approved by consensus last year after lengthy negotiations.

Critics say its broad language could lead to abuses of power and enable the cross-border repression of government critics.

"There were multiple concerns raised throughout the negotiation of the treaty around how it actually ends up compelling companies to share data," said Sabhanaz Rashid Diya, founder of the Tech Global Institute think tank.

"It's almost rubber-stamping a very problematic practice that has been used against journalists and in authoritarian countries," she told AFP.

'Weak' safeguards

Vietnam's government said this week that 60 countries were registered for the official signing, without disclosing which ones. But the list will probably not be limited to Russia, China, and their allies.

"Cybercrime is a real issue across the world," Diya said. "I think everybody's kind of grappling with it."

The far-reaching online scam industry, for example, has ballooned in Southeast Asia in recent years, with thousands of scammers estimated to be involved and victims worldwide conned out of billions of dollars annually.

"Even for the most democratic states, I think they need some degree of access to data that they're not getting under existing mechanisms," Diya told AFP.

Democratic countries might describe the UN convention as a "compromise document", as it contains some human rights provisions, she added.

But these safeguards were slammed as "weak" in a letter signed by more than a dozen rights groups and other organisations.

Tech sector

Big technology companies have also raised concerns.

The Cybersecurity Tech Accord delegation to the treaty talks, representing more than 160 firms including Meta, Dell and India's Infosys, will not be present in Hanoi, its head Nick Ashton-Hart said.

Among other objections, those companies previously warned that the convention could criminalise cybersecurity researchers and "allows states to cooperate on almost any criminal act they choose".

Potential overreach by authorities poses "serious risks to corporate IT systems relied upon by billions of people every day", they said during the negotiation process.

In contrast, an existing international accord, the Budapest Convention on Cybercrime, includes guidance on using it in a "rights-respecting" way, Ashton-Hart said.

The location for the signing has also raised eyebrows, given Vietnam's record of crackdowns on dissent.

"Vietnamese authorities typically use laws to censor and silence any online expression of views critical of the country's political leadership," said Deborah Brown of Human Rights Watch.

"Russia has been a driving force behind this treaty and will certainly be pleased once it's signed," she told AFP.

"But a significant amount of cybercrime globally comes from Russia, and it has never needed a treaty to tackle cybercrime from within its borders," Brown added. "This treaty can't make up Russia's lack of political will in that regard."