Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsDynamics of conservation value in Tenganan Pegringsingan spatial planning

Conservation in spatial planning is strongly related to environmental management. For this research, we specifically studied Tenganan Pegringsingan village’s local wisdom in environmental management.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

C

onservation in spatial planning is strongly related to environmental management. For this research, we specifically studied Tenganan Pegringsingan village’s local wisdom in environmental management. An ancient village in Bali, Tenganan Pegringsingan is famous for its customs. Many visitors make a trip to Tenganan Pegringsingan for that reason. Bali has two types of village, aga (mountain village) and dataran (plain village). Mountain villages are ancient and rare. Most of them are in the central regions of Bali. However, these villages have more variation in terms of physical characteristics than dataran villages. The main physical characteristic distinguishing an aga village from a dataran village is the open space extending from kaja to kelod (north to south), dividing the village in two.

Villages in Bali have at least four attributes: morphological, functional, symbolic and social. The first three attributes emphasize physical aspects, while the social one highlights non-physical or socio-cultural aspects more.

Liefrinck, in his studies in North Bali (1986-1987), stated that every village in Bali is a small republic with its own regulations or customary law [...] Liefrinck also stated that a customary village is a manifestation of the harmonious and static village, free from outside pressure, with the democratic and autonomous government. Furthermore, every customary village in Bali usually has a place of worship called Kahyangan Tiga, consisting of three temples: Puseh temple, Desa temple, and Dalem temple. Thus, a customary village counts as a territorial and religious community.”

Tenganan Pegringsingan, the village that is the focus of our study, is one of the ancient villages in Bali and home to many prehistoric relics and ideas, specifically those from the megalithic era. Currently the relics are well-maintained by the locals. For instance, the belief that views the buffalo as a sacred animal; a place of worship consisting of large stones and tiered terraces made of river stones; and open space in the middle of the village, covered in river stones, tiered and rising toward the mountain (Bukit Kaja) to the north of the village.

Buffaloes are free to roam the village, and the locals usually use them only for religious ceremonies (Usaba Sambah). Buffaloes are kept as cattle because villagers believe that they are the source of supernatural power and the symbol of fertility. The belief is strongly related to ancestral spirit worship, and the power is said to bring prosperity and fertility to the community. Tenganan Pegringsingan is no different from other mountain villages in Bali, but the diffusion process in Tenganan Pegringsingan tends to be slower due to the strong local culture.

In Tenganan Pegringsingan, there are several types of social organizations (sorted according to their roles and functions, from minor to major): customary village, gumi pulangan, sekeha teruna, sekeha daha, banjar subak, dadia, pemaksan, voluntary sekeha for a specific purpose and perbekelan. The regulations and organizational functions of the customary village, gumi pulangan, sekeha teruna, sekeha daha, and subak are relatively strong. On the other hand, banjar, dadia, pemaksan and sekeha have relatively weak organizational functions.

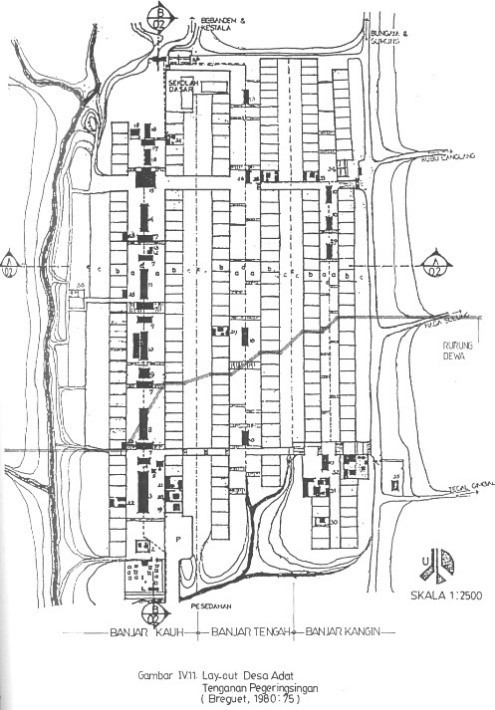

The settlement area in Tenganan Pegringsingan is surrounded by a wall that is 500 meters long and 250 meters wide. From the outside, the settlement area looks like a towering fortress. In each of the north, east and south walls, there is a gate, called a lawangan. The main entrance is on the south wall, facing Pesedahan village. However, the main entrance is not used anymore because of a parking lot next to the west wall. Tourists and residents usually enter the village through the small gate facing east.

The settlement area in Tenganan Pegringsingan is divided into three banjar: Banjar Kauh, Banjar Tengah and Banjar Kangin (Banjar Pande). Each banjar has two rows of houses, which are on the left and right of the village. These houses are built on the village’s communal land (the village’s karang), extending from the north to the south. Each banjar usually has a bale banjar and buildings for customary purposes. However, the complete facilities to conduct religious ceremonies, including the bale agung (the center of any activity concerning the village government, customs, and religion), are in Banjar Kauh.

Tenganan Pegringsingan villageIf viewed from the street (awangan), the houses resemble a long wall with a roof composed of dried coconut leaves. On the wall, which rises from the south to the north according to the topography of the settlement area, is the entrance to each house, facing the village street. At the back of the house is a gutter that functions as a drainage channel for rainwater and household waste, called teba pisan. It also serves as a boundary for each banjar.

In terms of geographical structure, Tenganan Pegringsingan is classified into three areas: the settlement complex, the rice field complex and the plantation complex (tegalan). In the settlement complex, the houses are of uniform pattern or structure. The village's binding customary rules are the reason for the same building structure. Each house usually consists of several buildings, from bale buga, bale tengah, bale meten and bale paon, to places of worship such as sanggah kemulan or penyimpangan. The patterns, shapes, positions and materials of specific buildings, such as bale buga and bale tengah, cannot be changed. The rule is more relaxed for others, such as bale meten and bale paon, which means the owners can design them according to their finances. However, these buildings must not be multi-story.

Tenganan Pegringsingan also strictly regulates matters concerning trees. The awig-awig of the village distinguishes trees into two kinds: those that are under the village’s ban (kayu kekeran desa) and those that are not. It is elaborated in Article 14 of the awig-awig:

Mwah wong desa ika sinalih tunggal angeker wit kayu ring sawawengkon desa Tenganan Pagringsingan, rawuh ing sagumin Tnganan Pagringsingan, iwit kayune kakeker, wit kayu namgka, wit tehep, wit tingkih, wit pangi, wit cempaka, wit duren, wit jaka, ne sadauh pangkung sabaler desa, tan kawasa ngrebah jaka kari mabiluluk, yang wus tlas biluluk ipune, ika jakane wnang rebah. Yan ana amurug angrebah kayu mwah jaka, wnang kang amurug kadanda olih wong desa gung arta 400, tur kang karebah wnang kadawut olih desa, manut trap kadi saban. Sadangin desa mangraris kagunung kangin, tka kawasa angrebah jaka. Mwah yan ana wong desane sinalih tunggal, matatajukan, sawawengkon den tinunjel, sagnaha, mawtu kini nilap witwitan, miwah papayo salwire, tka wnang kanganunjel mangentos kang kadilap, mwah kang rusak kadi jnar, tur kang anunjel tka wnang kadanda olih kang ngadruwe ne rusak, ingan agung alit dandane, tur wnang mamretista manut trap kadi saban.

Translated into English, this passage means:

“Anyone from the village growing trees within the area of Tenganan Pegringsingan village, including in the tegalan of Tenganan Pegringsingan village, is only allowed to grow (and use only when necessary) jackfruit trees, tehep trees, candlenut trees, champak trees, durian trees and enau trees in the west of the ravine in the north of the village. Cutting down an enau tree that still has flowers or fruit is prohibited. Cutting down an enau tree is allowed when the tree is no longer bearing fruit. Anyone who violates the rule of not cutting down trees or enau trees will have to pay a fine of 400 kepeng to the village. Furthermore, anything they cut down will be seized by the village. Cutting down enau trees is only allowed within a particular area, specifically from the east of the village to Bukit Kangin. Anyone in the village who produces flame within the village area that burns the trees or buildings, they have to replace anything burned or damaged. Furthermore, they have to pay a fine to the victims according to how severe the damage is and do a purification ritual.”

The spatial space in Tenganan Pegringsingan protects its people from outside influence, specifically disturbing or dangerous ones. Tenganan Pegringsingan, as a mountain village or an ancient village, has its own meanings that manifest as local wisdom (spiritual and material dimensions). Thus, the people of Tenganan Pegringsingan build legitimacy with symbols and beliefs inherited from their ancestors. According to the concept proposed by Norberg-Schulz, spatial environment/space has five meanings: pragmatic, perceptual, existential, cognitive and logical meanings. Then, at the practical level of life, that meaning is translated into safety, honor, status, order, education, and economy.

Through a participatory legal culture, the planning, utilization and control of space in spatial planning can go as planned but still reflect the noble values thriving in society. According to Abrar Saleng, local values, which can be universal in nature, that thrive in a community can be integrated into the substances or material of legislation that concerns the conservation of forests and the environment. This is because only such local values can serve as the principles and rules of law in the making of future forestry and environmental law.

A discussion with Putu Widnyana, a landowner in Tenganan Pegringsingan, revealed that modernization is affecting the village, causing a new dynamic. For instance, the paving of roads changed the footpath at the east of Banjar Pande, allowing access to motor vehicles. The change also creates a shortcut to Bungaya or Bukit Kaja village. Due to the shortcut, the supervision of the farms and rice fields cultivated by sharecroppers has become easier for the landowners of Tenganan Pegringsingan. This phenomenon threatens plant conservation, especially the conservation of enau trees, which produce dark fibrous bark (ijuk). In Tenganan Pegringsingan, the dark fibrous bark trade is prohibited because it is a crucial material for bale adat construction. However, the prohibition is now being threatened, especially seeing that the dark fibrous bark trade has begun to occur.

The occurrence can threaten the values or habits that are now established as a legal culture, which also serves as a manifestation of conservation efforts. If a change occurs to the legal culture that used to be firmly adhered to, the regulations or pararem of the village should address the change. The regulations will control the landowners and the sharecroppers and help the locals fulfill the need for dark fibrous bark by maintaining its conservation.

Author: Ni Made Jaya Senastri, Lecturer in the Master’s Program Postgraduate Law Studies at Warmadewa University