Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsWill Indonesian ethnic music survive modern times?

The government, ethnic music groups and other stakeholders join in to promote Indonesian ethnic music.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

The government, ethnic music groups and other stakeholders join in to promote Indonesian ethnic music.

The mid-1980s to early 2000s were golden years for the Sinar Baru troupe. During those years, the Betawi music group performed Jakarta’s ethnic music gambang kromong for birthday parties, weddings, and sangjits (bethrotals) around Jakarta, Bogor, Depok, Tangerang and Bekasi.

“We mainly lived on the road,” Ukar Sukardi, founder of the troupe, said.

“It was hard to find time to relax at home as we performed every day, except on Thursday nights.”

Every day after school, a lot of children also gathered at their headquarters in Gunung Sindur, Bogor, to learn to play the gambang (a kind of gamelan made of wood), bangsing (a kind of bamboo flute), tehyan (a sort of stringed instrument made of coconut shell and teakwood) and many other instruments used in Betawi music.

“But those were the old days,” the 74-year-old said with a sad smile. “These days, [people’s] taste in music has changed.”

Nowadays, the troupe, consisting of 25 musicians and singers, considers themselves lucky if they are invited to play twice a month. They now perform mainly in Bogor and its surrounding areas.

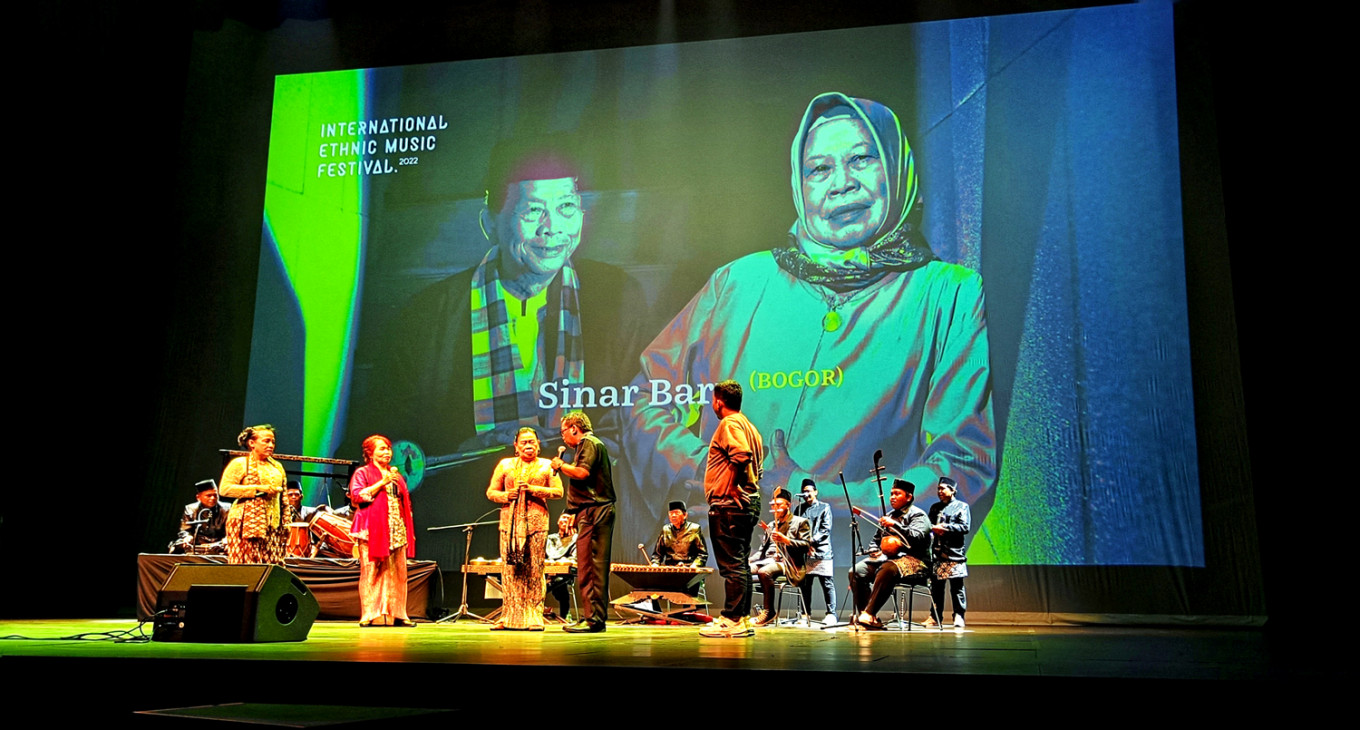

During the International Ethnic Music Festival, held by the music committee of the Jakarta Arts Council (DKJ) in Taman Ismail Marzuki (TIM), Jakarta, on Nov. 7-8, Sinar Baru presented nine classic gambang kromong scores to the audience.

Musical ensemble: The Sinar Baru troupe presents instrumental "gambang kromong" scores for the International Ethnic Music Festival at Taman Ismail Marzuki (TIM), Jakarta, on Nov. 7. (JP/Sylviana Hamdani) (JP/Sylviana Hamdani)Waning interest

The declining interest in Indonesia’s ethnic music is felt in almost every region of the country. While the archipelago is home to thousands of ethnic music from nearly every tribe, many among its young people now prefer modern genres.

“I’ve been very concerned with the situation since the early 2000s,” Rino Dezapaty, co-founder of the ethnic music group Riau Rhythm, said. “In those years, major labels bombarded Indonesia with Western pop, alternative and grunge music. A lot of TV and radio also played these songs.”

The massive promotions shifted the Indonesian young people’s preference for local ethnic music.

“I also conducted a small survey at that time and found out that Riau’s young people no longer recognized their ethnic songs at all,” Rino said. “It’s shocking.”

Declining interest in the country’s ethnic music impacts the performers and their groups.

More than half of the Sinar Baru troupe is over 40 years old. And hardly any children come to their headquarters after school to learn to play gambang kromong these days.

“Today’s kids prefer to play with their gadgets in their spare time,” Ukar Sukardi said.

As there are fewer demands for ethnic music performances, there are also fewer demands for musical instruments.

During a discussion at TIM, Indonesian drummer Gilang Ramadhan, who actively campaigns for Indonesian ethnic music, revealed that many makers of ethnic music instruments had now changed profession.

“Many of them gave me a call and said that they’re changing jobs to be a tukang bakso [meatball peddler],” Gilang said with a sad smile.

If this harrowing situation persists, Indonesian ethnic music may no longer be heard shortly. But thankfully, both the government and ethnic music stakeholders do not sit around waiting for it to happen.

Legal protection

In 2017, Indonesian President Joko "Jokowi" Widodo issued Law No. 5 Year 2017 regarding the Perpetuation of Indonesian Culture.

“We’re all blessed by Law No. 5 Year 2017, which clearly says that the state protects Indonesian ethnic music,” Gilang Ramadhan added.

In March 2018, Indonesian singers, musicians and producers congregated in Ambon for the Indonesian Music Conference (KAMI). During the three-day conference, the Indonesian music stakeholders issued a 12-point declaration that they will work together to develop a favorable ecosystem for Indonesian ethnic music.

In August of last year, the Education, Culture, Research and Technology Ministry, in collaboration with the Indonesia Karawitan Communication Foundation, held the country’s first Indonesian Traditional Music Congress, which decreed the establishment of the Collective Management Institution (LMK) for the archipelago’s traditional music.

“There are many LMKs for music in Indonesia,” Gilang explained. “But Indonesian traditional music, with its many complexities, requires its LMK.”

This new institution is assigned to list Indonesian ethnic songwriters, singers and musicians, as well as their works, to receive royalties from the National Collective Management Institution (LMKN) and to distribute the royalties to their members.

“We’re registering songwriters, singers and producers of Indonesian ethnic music as our members,” Gilang said.

A glimpse of tradition: Arababu, a stringed instrument from Maluku, is displayed during the International Ethnic Music Festival at Taman Ismail Marzuki (TIM) on Nov. 7-8. (JP/Sylviana Hamdani) (JP/Sylviana Hamdani)More exposure

Meanwhile, in the capital, the Jakarta Arts Council is also working hard to give more exposure to Indonesian ethnic music. Since 2019, the DKJ music committee has presented the Ethno Music Festival annually at TIM.

In 2021, the festival changed its name to the International Ethnic Music Festival, as it also features ethnic music from other countries.

This year, the two-day festival featured the performances of five ethnic music groups from Aceh, Bali, Riau, Bogor (West Java) and Ternate (Maluku) and a workshop on Latin American ethnic music and dance.

“We’re planning to conduct an open call next year to feature more ethnic music groups in the festival,” Adra Karim, chairman of the DKJ music committee, said during the festival.

The music committee is also planning for collaborative performances between Indonesian ethnic music and other musical genres in the same event next year.

“They won’t be just jamming sessions,” Adra said. “We want them to be thorough explorations of both musical genres that result in a better understanding and appreciation of Indonesian ethnic music.”

In-depth research for this collaborative program will be launched early next year.

Fusions and collaborations

Ethnic music groups are also taking initiatives to perpetuate their art.

During performances, the music troupe Riau Rhythm often combines the region’s Malay folkloric ensembles with Western music genres, such as classic disco, electro and RnB.

In 2018, the group collaborated with the Spanish Orquesta de Camara de Siero (OCAS) during their tour in Asturias, Spain.

“We’ve made various collaborations and explorations [of Riau’s ethnic music] so that today’s young generation will be able to relate to it,” Rino Dezapaty, co-founder of Riau Rhythm, said.

On Nov. 18-20, Riau Rhythm performed in the ASEAN India Music Festival in New Delhi, along with other ethnic music groups from the region.

Balinese ethnic music group Kadapat fuses Balinese gamelan and electro music into a unique, ethereal ensemble.

“At first, we played around with Balinese gamelan and digital instruments to overcome stagnation,” I Gusti Nyoman Barga Sastrawadi, co-founder of Kadapat, said. “But then we discovered that the digital element also helps bridge Balinese ethnic music to today’s young people.”

Ukar Sukardi, on the other hand, chooses to perpetuate traditional music from his immediate surroundings.

“My grandchildren and I approach kids in our neighborhood and encourage them to play gambang kromong at our place when they have time,” the grandfather of 11 said.

Four of Ukar’s grandchildren are now singers and instrument players in the Sinar Baru troupe. And thanks to their active campaign, six children in the neighborhood practice Betawi ethnic music at their headquarters from time to time.

One of Ukar’s grandchildren has created an Instagram and YouTube account for the group and regularly uploads their performances on these accounts.

“Hopefully, these uploads will generate a renewed interest in gambang kromong music among today’s young people,” the troupe’s founder said.

“I believe there’s still a future for Indonesian ethnic music,” Ukar concluded.